What does the hair on a man’s face mean? Since we are made in God’s image, what did God intend in creating males to grow facial hair? Does God prefer men—or at least certain classes of men—to be bearded or shaven? Is there a specifically Christian approach to facial hair?

Christians have been debating the place of the beard in society since the earliest days of Christianity. While it is beyond our poor competence to definitively answer this question, we can at least study the flow of Christian thinking on the matter. In this essay, we will take walk through history, tracing the development of the Church’s attitudes towards beards from the ancient Church to the end of the Renaissance. May you in reading find the depth and richness of the thought Christian thinkers have put into this subject is both surprising and enlightening, just as I did in writing.

“Proof of His Manhood”: The Church Fathers Encourage Beards

The Church Fathers were eager proponents of beards as a sign of manliness. The beard of a Christian signified his adherence to the natural order of things established by God. The patristic consensus seemed to be that a godly man was a bearded man, whether lay or clerical.

The first patristic author to write on beards was Clement of Alexandria (150-215). Clement’s view on beards echoes that of Aristotle and the stoic philosopher Epictetus, with whom he was quite familiar.

God planned that women be smooth-skinned, taking pride in her natural tresses, the only hair she has…but man He adorned like the lion, with a beard, and gave him a hairy chest as proof of his manhood and a sign of his strength and primacy. (1)

He went on to argue that since man’s hairiness was a sign of God’s order, “it is therefore impious to desecrate the symbol of manhood, hairiness” (2).

Tertullian also defended beards as emblems of the natural gender hierarchy willed by God. In his treatise On the Apparel of Women, he discusses modesty of clothing and grooming, primarily in women, although he does briefly mention men who trim their beards and shave around the mouth, comparing male shaving to the frivolities of women’s vanity:

…it is true, as it is, that in men, for the sake of women (just as in women for the sake of men), there is implanted, by a defect of nature, the will to please; and if this sex of ours acknowledges to itself deceptive trickeries of form peculiarly its own—such as to cut the beard too sharply; to pluck it out here and there; to shave round about (the mouth)…all these things are rejected as frivolous, as hostile to modesty. (3)

In both Clement and Tertullian we see the teaching that modesty involves accepting the body the way God made it. For a man to shave his God-given facial hair was a sign of self-indulgence and disorderly desire, as well as an affront to God’s hierarchy within society, as the beard functions as a symbol of man’s God-given authority.

If the beard was part of the natural order, would men have beards in heaven? Would men and women continue to have sexually differentiated bodies at all? This was a thorny theological problem; the Scriptures say, “in the resurrection they neither marry, nor are given in marriage, but are as the angels of God in heaven” (Matt. 22:30). The angels are asexual and genderless. Does this imply, therefore, that human beings will lack gender differentiation in heaven? If so, would men in heaven be beardless, since the Fathers—following the Greek philosophical tradition—affirmed beards as one of the most prominent symbols of masculinity?

St. Augustine followed the Greco-Patristic tradition in associating beards with manhood. He had written:

The beard signifies the courageous; the beard distinguishes the grown men, the earnest, the active, the vigorous. So that when we describe such, we say, he is a bearded man. (4)

Given this, Augustine affirmed the presence of beards in the resurrection. As the beards were signs of God’s order and man’s spiritual authority, the perfected man of the resurrection would necessarily be bearded. It was an ornament of the truly masculine soul, a sign of beauty rather than practical necessity. As such, it pointed towards the life to come, when the full splendor of manhood would be realized in the resurrection (5). In this, he was joined by Jerome, who affirmed that in heaven, men would still be men and women still be women, along with their biological differentiations—including beards (6).

The late 4th century Apostolic Constitutions appeals to the Old Testament Book of Leviticus in support of a general prohibition against shaving, considering shaving an “unsuitable” practice which makes a man “abominable to God”:

Nor may men destroy the hair of their beards, and unnaturally change the form of a man. For the law says: “You shall not mar your beards.” (cf. Lev. 19:27) For God the Creator has made this decent for women, but has determined that it is unsuitable for men. But if you do these things to please men, in contradiction to the law, you will be abominable with God, who created you after His own image. If, therefore, you will be acceptable to God, abstain from all those things which He hates, and do none of those things that are unpleasing to Him. (7)

The early Church was ever wary of “Judaizing,” and strenuously rejected the ceremonial aspects of the Jewish law that were fulfilled by the New Covenant. The fact that Leviticus 19:27 is thus cited in the Apostolic Constitutions suggests the Fathers did not view the Levitical prohibition against shaving as part of the ceremonial but rather the natural law. As an aside, it is questionable whether Leviticus even prohibits shaving absolutely. It likely prohibits marring the edges of the cheek in a very specific manner proper to pagan worship, as the prohibition on marring the edges of the beard is sandwiched between passages against witchcraft (19:26) and slicing the flesh as a sign of mourning (19:28), both pagan practices. But the meaning of Leviticus is ultimately irrelevant here; the Church Fathers believed it prohibited shaving and its citation in the Apostolic Constitutions further demonstrates the patristic consensus that male beardedness was part of the natural order—and ergo, shaving was contra naturam.

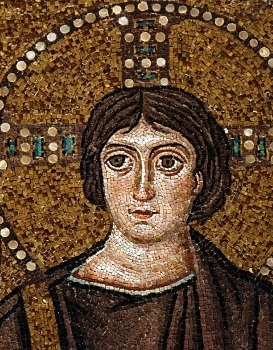

These theological teachings also provided justification for a bearded Jesus. The image of Christ was not fixed until the 4th-5th centuries; prior to this time, it was typical to portray Jesus as a beardless Greco-Roman youth, his clean-shaven face representing the eternal youthfulness implied by His divinity. As late as the time of Justinian, it was not uncommon to see beardless depictions of Christ, especially when His divinity was emphasized. But the patristic consensus on male beardedness as signifying perfected masculinity facilitated the transition to a bearded Christ, which became increasingly common by the 400s and was universal by the 600s.

Middle Ages: Beardlessness is Godliness

The Church Fathers of the late Roman Empire had equated beardedness with the natural order established by God. As we move into the Middle Ages and the rise of Christendom, we will witness a complete inversion of this patristic ideal with the medieval concept of shaving and purity. Indeed, it is from the Middle Ages that the west has inherited its bias that a well-groomed man shaves every day.

The association between a clean-shaven face and moral purity grew over time, but the transition seems to have occurred due to the cultural and political changes that followed the Germanicization of Europe after the fall of the Western Roman Empire. Germanic tribes such as the Franks, Goths, and Saxons wore their hair long and flowing. Some bore great beards; others, like the Franks, preferred huge mustaches. Faced with their civilization being overrun by hairy pagan hordes, the Christian clergy—especially in Rome—tenaciously clung to their short hair to maintain their distinct identity. This extended to beards as well. Beards were not at first prohibited, but mandated to be kept trimmed. A synod from around 503 convened under St. Caesarius of Arles decreed that “a cleric is to allow neither hair nor beard to grow freely.” (8) This did not prohibit beards, but rather beards that were untrimmed. Long hair and beards were associated with paganism; the Second Council of Braga (563) forbid clergy from wearing their hair long “like the pagans” (9).

Since Germans wore their hair long, maintaining short hair and well-trimmed bears (or going clean shaven) served to differentiate the clergy from the laity. We can see this in the legislation of the Fourth Council of Toledo, convened under St. Isidore of Seville in 633. The 41st canon of this council stated:

In Galicia, heretofore, the clerics have worn long hair, like the laity, and have only shorn a little circle in the middle of the head. This may not, in future, be so. (10)

The canon refers to the practice of Galician clerics being distinguished only by a small tonsure; in other respects, they resembled layman, especially in the wearing of long hair. The decree implied that further distinction between clergy and laymen was needed, specifically, that the hair should be shorn and the tonsure enlarged.

During these centuries, short hair became a sign of the priesthood. Pope Gregory the Great argued that being shorn of hair and beard was a unique sign of the sacramental priesthood of the New Testament (as opposed to the Jewish priesthood, which was long haired and bearded); in Moralia in Job, Gregory argues that being shorn is fitting for one who offers the Sacraments, and is symbolic of the cutting off of worldly thoughts and desires:

What is signified by the hair that was shorn but the sublimity of Sacraments? What by the head but the High Priesthood? Hence too it is said to the prophet Ezekiel, ‘And thou, son of man, take thee a sharp knife, take thee a barber’s razor, and cause it to pass upon thine head, and upon thy beard; )Ezek. 5:1) clearly that by the Prophet’s act the judgment of the Redeemer might be set out, who when He came in the flesh ‘shaved the head,’ in that he took clean away from the Jewish Priesthood the Sacraments of His commandments; ‘and shaved the beard,’ in that in forsaking the kingdom of Israel, He cut off the glory of its excellency….

What do we understand in a moral sense by hair, but the wandering thoughts of the mind? The shaving of the head, then, is the cutting off of all superfluous thoughts from the mind. And he shaveth his head and falls upon the earth, who, restraining thoughts of self-presumption, humbly acknowledges how weak he is in himself. (11)

In the succeeding years, a clean shaven face and short hair came to be associated with priestly status, such that by 721, Pope Gregory II was threatening long haired clerics with excommunication. (12) This idea of shaving as a commitment to holiness came to apply to the beard as well. By the 7th-8th centuries, monks were expected to be clean shaven as a sign of their vows. A monk, upon his profession, would tonsure the crown of his head and have his beard shorn off, if he had one. In Anglo-Saxon England, the very word for a cleric was bescoren man, a “shorn man,” as we see in the Laws of Wihtred (c. 725). The laws of Alfred the Great (9th century) also tell us that priests were clean-shaven in England.

Around this time, secular men, as well, were going clean shaven more. When the Franks converted to Christianity, they tended to cut their long hair short after the Roman fashion while maintaining their mustaches as was custom. This custom became universal by the time of Pepin the Short (751-768) and Charlemagne (768-814).

Though Charlemagne was often depicted as bearded in legend and song (in the Song of Roland he is “white of hair and beard,” his beard flowing all the way down to his horse’s harness), the historical Charlemagne was beardless, preferring close cropped hair and the bushy Frankish mustache. (13) While the famous golden reliquary bust of Charlamagne depicts the famed emperor with a curly beard, this is from the 14th century and does not reflect the way he actually looked. The famed “Equestian Statue of Charlemagne,” on the other hand, dates from the 9th century and accurately depicts how Charlemagne would have looked. Here we see him with a close cropped “bowl cut” of the Roman fashion, clean shaven, with a flowing Frankish mustache.

Charlemagne’s successor, Louis the Pious, mandated in a capitulary of 816 that all monks shave their faces at least once a month. (14) Secular priests and laymen followed suit, and by the mid-9th century it was common for men in western Europe to shave their faces entirely. This scandalized the Arabic traveler, Harun ibn Yaha, who visited Rome in 886. Ibn Raha wrote, “young and old shave their beards off entirely; they do not leave a single hair.” (15) When he asked about this custom, he was told it was the Christian thing to do. Christopher Oldstone-Moore, in his study of facial hair Of Beards and Men, rightly observes that this episode demonstrates how the Carolingian preference for clean-shaven men was setting up an paradigm pattern of masculine headship:

This clearly made no sense to Harun, for it rejected the natural link between patriarchy and beardedness that even western Europeans [traditionally] acknowledged. What he failed to realize, however, was that the Latin church was formulating an alternative form of patriarchy based on the unique spiritual authority of celibate professionals [literally, those who are “professed”]. (16)

This also was a marked departure from the Byzantine tradition, which continued in the earlier patristic view of beards as signs of God’s natural order that were fitting for clerics and laymen alike. Most Greek Orthodox polemics against Latin Christendom of this time also included barbed attacks against the reprehensible practice of priestly shaving. These attacks were so fierce as to prompt a response from the revered theologian Ratramnus (d. 868), who built upon the analogical symbolism of the beard taught by Gregory the Great. Ratramnus argued that the manner of the physical face was a reflection of “the face of the heart”:

In the shaving of their faces [priests] show the purity of their hearts, for the appearance of the head makes known the appearance of the heart…[just as shaving removed hair from the face of the head] “the face of the heart ought to be continually stripped of earthly thoughts, in order that it may be able to look upon the glory of the Lord with a pure and sincere expression, and to be transformed into it through the grace of that contemplation. (17)

The next great innovation came during the pontificate of Pope St. Gregory VII (1073-1085). At the crux of Gregory’s reform was the independence and professionalism of the clergy. We are well aware of Gregory’s insistence on clerical celibacy and his crusade against simony as integral parts of his vision. He also, however, extended the prohibition on beards from monks to the entire clergy through letters to bishops and secular princes. For example, in 1080 the pope wrote to Orzocco, a prominent judge of Cagliari, Sardinia, encouraging him to support the Gregorian Reform in Sardinia. He says,

We hope that Your Excellency will not be offended that we have required your archbishop James to follow the custom of the Holy Roman Church, mother of all churches and especially yours—namely, that he, our brother, your archbishop, should observe the practice of the whole Western Church from the very beginning and should shave his beard. We also require of your highness that you receive him as your pastor and spiritual father and, in accordance with his advice, compel the whole clergy under your control to shave their beards. You will also confiscate the property of those who refuse, will turn it over to the Church of Cagliari, and will prevent them from any future concern with it. You will give the archbishop every assistance in maintaining the dignity of the churches. (18)

Gregory was manifestly wrong when he said such was practice of the Western Church “from the very beginning.” Nevertheless, the letter reveals the way the Church authorities had come to view shaving. Maintaining a clean-shaven clergy was part of “maintaining the dignity of the churches.” Gregory considered it such an important part of clerical discipline that he was willing to enlist the aid of the secular arm to enforce it, even to the point of confiscation of property.

A Canonical Fraud

Gregory’s assertion that clean-shaven clergy was an ancient custom is interesting, as it seems to come from a willful mistranslation of an earlier canon. A collection of canon law published in 1023 included three statutes mandating clerical shaving; this is undoubtedly what Gregory referred to when he spoke of “the practice of the whole Western Church from the very beginning.” The canons of 1023 were purportedly from Statua Ecclesia Antiqua, a collection of disciplinary canons from southern Gaul dating from between 442 and 506; it also included the decrees of the synod of St. Caesarius (503) mentioned earlier in this essay. The publication of 1023 had misconstrued the earlier collection to make it appear that clerical shaving was an ancient practice. For example, the 6th century Statua Ecclesia Antiqua contained the following phrase:

Clericus nec comam nutriat nec barbam radat.

A cleric ought neither grow his hair long, nor shave the beard.

This text, however, when included into Canon 203 of the 1023 collection, was slightly altered to read:

Clericus nec comam nutriat sed barbam radat

A cleric ought not grow his hair long, but [should] shave the beard. (19)

The 1023 canonical collection was thus altered to give the false appearance that clerical shaving was of great antiquity in the west.

Beardlessness as a Special Prerogative of the Professed

In years following the Gregorian Reform, shaving was viewed as an exclusively spiritual act. As such, it created a sharp contrast between the cleric and the layman. The clergy tended to view beardlessness the way they viewed the tonsure, as a unique sign of those professed to God in a special way.

This was reaffirmed at the regional Council of Toulouse (1119), which threatened with excommunication any cleric who let his hair and beard grow like a layman; Alexander III ordered clerics who refused to shave the beards to be forcibly shorn by their archdeacon, if necessary. This dictate was incorporated into the text of canon law with the Decretals of Gregory IX.

The opinion of the high Middle Ages held that being clean-shaven was only suited to the clergy. Shaving was an act of devotion for the cleric but perverse in a layman. During the 11th and 12th centuries, clerical writers vigorously defended the special sign of their status by condemning laymen who shaved. William of Volpiano, a monk of Burgundy, denounced the “smooth faces” of laymen as an sign of vanity. Siegfried of Gorze, a German bishop, censured the nobles of the Holy Roman Empire who were increasingly going beardless, warning that shaving would corrupt the morals of the German people. Othlonus, a scholar of Regensburg, wrote of a layman who was rebuked by a priest for shaving. According to Othlonus, the layman was told, “Because you are a layman, according to the custom of the laity, you ought not to go around with a shaved beard. But instead you, in contempt of divine law, have shaved your beard like a cleric.” (20) Othlonus tells us that the layman promised to stop shaving, but soon reneged on his promise. In retribution for violating “divine law,” he was captured by his enemies who gouged out his eyes.

A century later, Alan of Lille, a French monk, complained about the haughty pride of contemporary laymen who shaved:

With the help of a comb they assemble their hairs in a council so peaceful that a gentle breeze could not stir up a commotion between them. Invoking the patronage of the scissors, they crop the ends of their bushy eyebrows, or they pluck out by the roots what is superfluous in this same forest of hair. They set frequent ambushes with the razor for their sprouting beard with the result that it does not even dare to show a small growth…Alas! What is the basis for this haughtiness, this pride in man? (21)

Interestingly enough, though we sometimes see accusations of effeminacy leveled at laymen who shaved, the ultimate reason the clergy opposed lay shaving was because it was an usurpation of the clerical state. Shaving was not inherently good or bad; its value depended upon one’s state. The layman who went about clean-shaven was essentially boasting that he had something he did not. The medievals saw a hairless face not as an an absence of something, but as the presence of something better. Here we come to the idea of the “inner beard.”

The Inner Beard

By the high Middle Ages, it was common for Cistercian monasteries to be composed of two classes of monks: “choir monks” who prayed, and “lay brothers” who were recruited from the peasant class and worked in the monastery’s fields. The choir monks were clean shaven, while the lay brothers wore close cropped beards.

In 1160, the Cistercian Abbot Burchard of Bellevaux was alarmed by the lax discipline he heard of some of the lay brothers in Bellevaux’s daughter house of Rosieres. Burchard wrote them a letter, gently chastising them for their bad behavior. In the letter, he invoked a symbol from Isaiah—the burning of garments as a sign of judgment—warning the lay brothers that they might have their beards burned in the fires of judgment if they refused to mend their ways. The lay brothers took umbrage at this jab at their appearance. Was not the beard the distinctive sign of the laity? Why were the lay brothers required to grow them just so the monks might abuse them and their hair?

The result was history’s first book about beards, Burchard’s Apologia de Barbis (“Explanation Concerning Beards”). In this work, Burchard sought to establish the purpose and role of beards in God’s order. Burchard delighted in the subject matter, giving thorough attention to every aspect of the question: the beard as representing the moral self, as a sign of right social manners, and as a reflection of God’s glory in the order of His creation.

Drawing on St. Augustine, who surmised that the beard represented masculine virtue, Burchard developed a typology of the beard: hair on the chin signified wisdom, under the chin denoted strong feeling, hair along the jaw was a projection of virtue, etc. He summarizes his typology thus:

All in all, a beard is appropriate to a man, as a sign of his comeliness, as a sign of his strength, as a sign of his wisdom, as a sign of his maturity, and as a sign of his piety. And when these things are equally present in a man, he can justly be called full-bearded, since his beard shows him to be, not a half-man or a womanly man, but a complete man with a beard that is plentiful on his chin and along his jaw and under his chin. (22)

But if this were true, would it not imply that monks and clergy deprive themselves of all these virtues by shaving themselves? Burchard answers that this beard truly does symbolize all these strengths, but monks forego these signs of natural strength for a higher calling: the cultivation of the “inner beard.”

The idea of the inner beard is that what the physical beard represents literally, the lack of a beard represents spiritually. The beard is a sign of physical manliness; the lack of a beard signifies spiritual vigor. The gray hairs of an aged man signify natural wisdom; the clean-shaven face of the monk signifies spiritual wisdom. A fine beard is a mark of physical attractiveness; the shorn monk has rather chosen to make his soul attractive. Masculinity is a mirrored reality, the inside an inversion of the outside. Thus, it is not that monks lack beards; it is that everything that the beard represents grows “on the inside.” This is the “inner beard.”

This was not a novel idea to Burchard; we have seen how Pope Gregory the Great equated cutting hair with putting away sin. In Burchard’s own life, the famed St. Bruno of Segni (d. 1123) had written:

Men who are strong are superior to those who only wish to seem so. Therefore, let our interior beard grow, just as the exterior is shaved; for the former grows without impediment, while the latter, unless it is shaved, creates many inconveniences and is only nurtured and made beautiful by men who are truly idle and vain. (23)

Burchard takes up these ideas to establish the beard as the distinguishing mark of a layperson, reinforcing the distinction between choir monks and lay brothers. For monks, the hair is shaved as a crown, and the beard is cut off to signify the dismissal of all superfluous thoughts; by contrast, lay brothers neither wear a tonsure nor shave their beards. Burchard does advise them, however, to “let the beard appear to be neglected in rustic lack of fashion rather than shaped with excessive care into lustful composition.” (24) In this way they can maintain the appearance proper to their state while avoiding falling into vanity. He concludes his essay by observing that in heaven, all men would wear beards; the “inner beard” would become outer and vice versa.

Lay Shaving as a Sign of Piety

There were, however, certain instances when laymen were encouraged to shave their beards off as a sign of piety—for example, in fulfillment of a vow, or as a sign of fidelity to the Church, or an act of penance. An example of this comes from the life of King Henry I of England.

In the year 1100, control of England was contested between two sons of William the Conqueror, Henry, and Robert, Duke of Normandy. The bishops of the Church were eager to back whichever candidate would support the rights of the clergy. King Henry promised the influential Bishop Serlo of Seez (Normandy) that he would defend the rights of the Church and the clergy. The diocese of Seez had been particularly brutalized by the warfare between Henry and Robert and Bishop Serlo was eager to secure Henry’s promise of goodwill.

In Easter of 1101, King Henry and his retinue attended Mass at Bishop Serlo’s cathedral. The bishop noticed that Henry and his retinue were keeping long beards and their hair long (which had begin to come back into fashion). Serlo launched into a fiery sermon against the vanity of long hair and large beards. He stated that vain men refuse to trim their beards for fear that their whiskers would prick their mistresses. Moreover, he said, their bushy countenances made them look more like Muslims than Christian men. Long hair and beards were for penitents, he argued, “who proclaim by their outward disgrace the baseness of the inner man.” (25) Then, at the end of what must have been an incredibly awkward homily for Henry to sit through, the bishop produced a pair of scissors and invited the king and his retinue to step forward and be trimmed as a sign of their submission to the Church and fidelity to God. The king and his men processed to the front of the Church and were accordingly shaved by the bishop.

King Louis VII of France (r. 1137-1180) shaved his beard as an act of penitence. During a war against the Count of Champagne, Louis’s troops committed many barbarities, including burning down a church with a thousand men, women, and children inside. Louis found his court placed under papal interdict and sank into a deep depression. St. Bernard of Clairvaux went to visit the young king and counseled him to make a fresh start. King Louis, Bernard said, should repent of his sins, make amends with pope and count, and go on a penitential pilgrimage to the Abbey of St. Denis. King Louis agreed. He walked to St. Denis, and upon his arrival, shaved off his beard in sign of penitence.

Louis VII was a crusading king, as was his grandson Louis IX. Shaving was also popular among crusaders, for various reasons: it was Frankish custom, and it helped distinguish them from their Muslim opponents. Muslims who came under Christian dominion were required to grow their beards long. During the siege of Antioch in 1098, crusaders accidentally killed each other, as their beards had grown out during the long campaign. Bishop Le Puy, papal legate, begged them to shave so such a tragedy could be avoided in the future. In 1190, during the Third Crusade, an Arab supply ship under the control of Saladin managed to break through the crusader blockade at Acre when its crew shaved their beards off to pass as westerners.

The status of beards among the military orders is an interesting question. Like most crusaders, the Templars and Hospitallers began as beardless, calling to mind their status as monks. Over time, however, they grew their beards out long. The rationale was simple: this made it clear that they were not choir monks, but fighting monks. The Templars and Hospitallers cultivated the exterior strengths represented by the physical beard, and as such thought it fit to wear one. Interestingly enough, before King Philip the Fair of France had the leaders of the Templars executed in 1312, he had them shaved as a sign of degradation.

Despite clerical opposition, laymen continued to shave. Clerical complaints proved futile. By around 1300, almost all laymen were going clean shaven and the clergy gave up their protest. By this time, facial hair no longer distinguished different classes of men. Instead, a man’s clean shaven face signified general qualities of civilized society that all men should aspire to, regardless of their social station. We will conclude this section with an anecdote from Dr. Oldstone-Moore’s work, telling of the meeting between a Byzantine Emperor and a Spanish nobleman in Italy during the 15th century:

A dinner conversation in 1438 serves as a fitting summary of the story of medieval facial hair. Pero Tafur, a Spanish nobleman and adventurer, found himself conversing in Italy with the visiting Byzantine emperor John VIII. The subject was Tafur’s beard, or rather the beard he had recently removed after returning to Western Europe after a long residence in Constantinople. The emperor insisted that Tafur had made a mistake, because a beard was “the greatest honor and dignity belonging to man.” Tafur, speaking for the entire Latin West, replied that “we hold the contrary, and except in case of some serious injury, we do not wear beards.” Tafur was reading from a script the Roman church had written. Even seven hundred years later, the descendants of Western Europe instinctively seen goodness, discipline, and honor in a clean shaven man. (26)

Renaissance Humanism: The Bearded Glory of Man

The Humanist movement of the Renaissance signaled a renewed interest in the mores of the Greco-Roman world. The Renaissance brought with it a new way of looking at facial hair; instead of seeing it as a symbol of sin to be purified, Humanists saw it as emblematic of human skill and potential. The age saw the pendulum swing again back to the “natural law” vision of the male beardedness that had characterized the late Roman Empire.

In 1520, in anticipation of the meeting of the Field of Cloth of Gold between Henry VIII and Francis I of France, both young kings agreed to grow their beards out as a sign of friendship. Their newfound enthusiasm for beards was not unique to the Europe’s royal courts: all throughout Europe men were embracing beards. Even Pope Julius II, at the siege of Bologna, grew a beard, the first papal beard in 140 years.

The beard movement began in Italy, the heart of the Humanist movement. It was given great impetus after the sack of Rome in 1527 when Pope Clement V decided to grow his beard out as a sign of penance. In 1531, he granted permission for the clergy to grow beards for the same reason. Clerical apologists, writing in the early years of the Reformation, latched on to the trend and promoted it in hopes that it would reinvigorate clerical masculinity. A Humanist author, Pierio Valeriano, believed that the priesthood needed to recover respectability in light of the scandals that brought about the Reformation. His 1531 Pro Sacerdotum Barbis (“In Favor of Beards for Clergy”) argued in favor of a bearded clergy from reason, natural law, and the dictates of the ancients. But more importantly, he dug back into patristic sources to demonstrate that no ancient canons banned facial hair; quite the opposite. He argued for beards not merely from an appeal to ancient authority, but to health: according to Valeriano, beards expelled bad humors from the body, prevented tooth decay, and protected the skin from extreme temperatures. He wrote:

Why should we be ashamed of our beards, if it has been revealed to us exactly what the beard is, and how it adorns the dignified and honorable man, and how much it contributes to the status and reputation of the priest. (27)

Valeriano spoke for the spirit of the age; by the 1530s beards were becoming fashionable for priest and layman alike, although there was still some controversy—in France, universities, law courts, and cities fought back against the bearded fad by passing legislation requiring various professional classes to shave.

Some in the hierarchy were alarmed at the promotion of beards, especially as it coincided with the rise of Protestantism; had not Martin Luther grown his beard out after leaving the monastery as a snub at the Church? St. Charles Borromeo was the most prominent voice against the new trend. He cited medieval justifications and the well-attested allegorical association of shaving with the cutting off of impure thoughts. Beyond this, he actively encouraged diocesan synods throughout Europe to punish priests who failed to shave. The Church—indeed, all of Christendom—seemed divided on the question of beards. The divide between bearded and clean shaven ran across many sectors of society: the bearded Humanist and the clean-shaven medievalist, the shorn Catholic versus the whiskered Protestant, the hairy-faced commoner and the smooth-skinned professional.

Conclusion

The popularity of beards would continue to ebb and flow in the centuries after the Renaissance, but the debates lost their religious overtones. As for the Church, clerics continued to wear beards until it fell out of style in the 17th century, reverting back to a smooth-faced clergy, as so remained the practice into modernity. But by that time, Christians no longer argued whether facial hair was more pleasing to God; debates instead turned on matters of fashion, aesthetics, and perception of what it meant to be a gentleman in good society. These discussions are interesting as well, but do not pertain to this essay.

In conclusion, we can see that the Catholic attitude towards beards has vacillated between two positions, largely relative to social conditions in the secular world which the Church then responded to accordingly. For simplicity, I am calling these two positions the “Natural Law” and the “Clerical.” We could summarize them as follows:

Natural Law: Beards reflect the power and headship of males over the human race and as such reflect the natural order of God structured into human society.

Clerical: Beards represent the untamed passions of mankind; shaving them off is a symbol of purity and the renunciation of sin.

These positions have waxed and waned throughout Christian history because both contain truth. The beard certainly exemplifies the best aspects of masculinity: courage, power, wisdom, fatherhood. But the beard must be kept within proportion by reasoned grooming; an unkempt beard represents nature untamed by reason; when artists want to depict a wild, savage man, he is inevitably portrayed with a scraggly beard and bushy, untidy hair. Beards can thus also signify man reduced to an animalistic state. When tamed by reason and brought under cultivation, it is full of beauty and splendor; when untamed, it signifies barbarity and raw, animalistic impulse.

The beard is thus a microcosm of mankind himself.

(1) Clement of Alexandria, Paedagogus, Book III, Chap. 3

(2) Ibid.

(3) Tertullian On the Apparel of Women, Book II, Chap. 8

(4) St. Augustine, Exposition on Psalm 133, 6

(5) Christopher Oldstone-Moore, Of Beards and Men (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015), 77

(6) Ibid., 76

(7) Apostolic Constitutions, Book I, Section 2

(8) Herbert Thurston, “Beard,” in The Catholic Encyclopedia (New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1907). http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/02362a.htm

(9) Oldstone-Moore, 83

(10) Charles Joseph Hefele, A History of the Councils of the Church, Book XV, Sec. 290

(11) Gregory the Great, Moralia in Job, Book II, 57, 82

(12) Oldstone-Moore, 83

(13) See Song of Roland, 16, 159

(14) See discussion in Mary Bateson, “Rules for Monks and Secular Canons After the Revival Under King Edgar,” The English Historical Review, Vol. 9, No. 36 (Oct., 1894), pp. 690-708

(15) Oldstone-Moore, 84

(16) Ibid.

(17) Ratramnus of Corbie, Contra Graecorum Opposita Romanum Ecclesiam Infamantium, quoted in A. Edward Siecienski, Beards, Azymes, and Purgatory: The Other Issues That Divided East and West (Oxford Univeristy Press: Oxford, U.K., 2022), 45

(18) The Correspondence of Pope Gregory VII, translated with an introduction by Ephraim Emerton (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1969), 164. This citation is from Book VIII, Letter 10 of the Registrum of Gregory VII, “To Orzocco, Judex of Cagliari”

(19) Oldstone-Moore, 88

(20) This and other references in this paragraph, ibid.

(21) Alan of Lille, The Plaint of Nature (Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies, 1980), 187

(22) Apologia de Barbis, quoted in Oldstone-Moore, 92

(23) See Sebastian Coxon, Beards and Texts: Images of Masculinity in Medieval German Literature (London: UCL Press, 2021), pp. 7, 9

(24) Oldstone-Moore, 93

(25) Ibid., 96

(26) Ibid., 104

(27) Siecienski, 71

I also owe recognition to Dr. Christopher Oldstone-Moore’s study of facial hair in western civilization, Of Beards and Men, which provided the basic outline of this essay and drawing my attention to some of the pertinent source material.

Phillip Campbell, “The History of Beards in Western Christendom,” Unam Sanctam Catholicam, September 4, 2022. Available online at http://unamsanctamcatholicam.com/2022/09/the-history-of-beards-in-western-christendom