In their attempts to discredit Catholic veneration of the Blessed Virgin Mary and demonstrate that Mary takes the place of Jesus in Catholic piety, Protestants have sometimes made the assertion that different Catholic shrines around the world depict Mary as crucified for the sins of mankind, essentially sending the message that Mary, not Jesus, is the Savior of the world. This accusation appears in the popular evangelical book Fast Facts on False Teachings by Ron Carlson and Ed Decker (2003), where the authors speak of an altar in the Cathedral of Quito, Ecuador, that features an altar with a crucified statue of Mary above it. The same accusation is made in the video Catholicism: Crisis of Faith by Lumen Productions, an anti-Catholic video produced by disgruntled ex-Catholics. The implication is that Catholics believe they owe their salvation to Mary, not Jesus.

It is true that there are depictions of a crucified female figure in the Cathedral of Quito in Ecuador. These images also appear in many of Spanish and Portuguese speaking countries; sometimes images of the crucified woman are even borne aloft in processions. The only problem with the fundamentalist critics of Catholic Marian devotion is that this crucified woman is most certainly not the Virgin Mary.

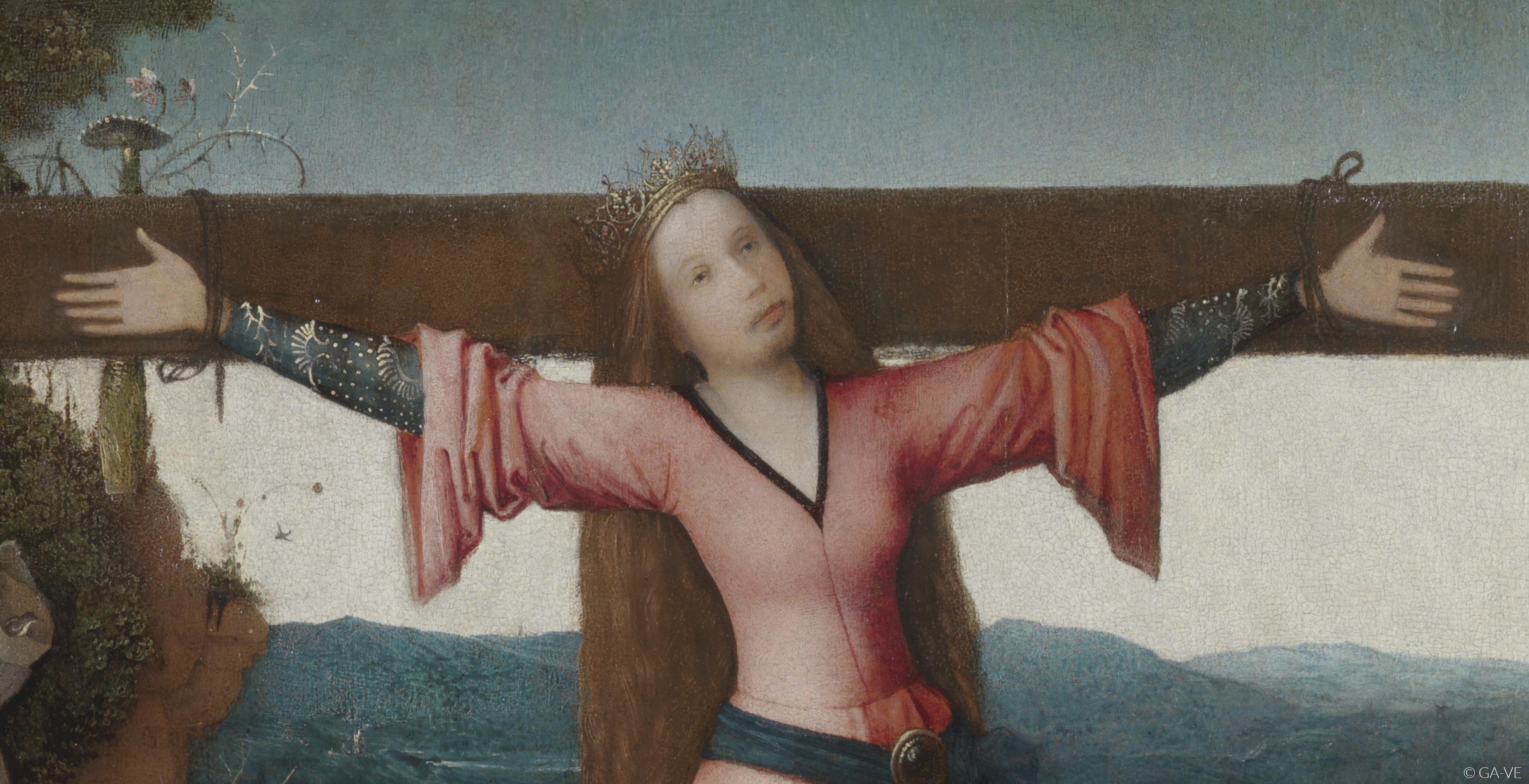

The crucified woman is St. Wilgefortis, also known as St. Liberata in Spanish speaking countries. Liberata, according to legend, was the daughter of a pagan Portuguese prince who betrothed her to another pagan warlord despite her wishes to remain a virgin. When she openly disobeyed her father’s wishes by refusing to marry and attempted to disguise herself as a man, her enraged father had her crucified. St. Wilgefortis-Liberata is the patron saint of women in abusive relationships. She appears above the side altar at Quito for the same reason any saint appears above a side-altar: it is common for side-altars to be dedicated to specific saints and for those altars to named after those saints. Anyone who has ever visited a medieval cathedral knows this.

Devotion to saint Liberata grew throughout later the Middle Ages and reached its peak around the 15th-16th centuries when many churches throughout the Spanish-Portuguese speaking world were named after her. In Portugal, there is still an annual procession in which the statue of St. Liberata is borne aloft.

The historicity of Wilgefortis was called into question beginning around the time of the Protestant Revolt, since there was never any record of when she lived, the name of her father, relics of her body, etc. Eventually, she came to be regarded as a “fabulous” saint (i.e., one who received popular, unofficial veneration but who never really existed).

The common explanation for devotion to the saint is that originated from a misinterpretation of the famous “Volto Santo” of Lucca in Italy, which is a representation of the crucified Savior, clothed in a long tunic, His eyes wide open, His long hair falling over His shoulders, and His head covered with a crown. In the early Middle Ages it was common to represent Christ on the cross clothed in a long tunic, and wearing a royal crown; but since the eleventh century this practice has been discontinued, and over the years, as artistic style changed, the tunic began to suggest a feminine appearance to the people of the later Middle Ages. Thus it happened that copies of the “Volto Santo” of Lucca, spread by pilgrims and merchants in various parts of Europe, were no longer recognized as representations of Jesus, but came to be looked upon as pictures of a woman who had suffered martyrdom, who was designated as Wilgefortis in English speaking countries and Liberata in the Romance tongues. She is also called “Uncumber” and Kummerinis”, but her various names are usually variations of the word “liberated” or “unencumbered”, referring to the story of her wishing to be free from an unwanted betrothal.

Devotion to Wilgefortis-Liberata (whose feast day was honored on July 20th) was discontinued after the 16th century when Catholic scholars of the Counter Reformation era definitively debunked her as a historical character, although local devotion continued, particularly in German speaking countries, into the modern day.

It is a fascinating tale, and an example of how not every legend and tradition found throughout Christendom at any given time is necessarily true. It hardly can be cited as an example of the Church’s history or teaching being fundamentally errant; Wilgefortis was never officially canonized, though her name did appear in some local breviaries.

What is fascinating is the manner in which many Protestants are so eager to believe their own worst fears that Catholics ultimately worship Mary instead of Christ that they would honestly believe that these statues of St. Liberata depict the Blessed Virgin dying for our sins on a cross (nevermind that such a belief would contradict another belief of Catholics anathema to Protestants: that Mary was assumed bodily into heaven, which in the western tradition, tends to be seen as occurring while Mary is still alive). It confirms that the very worst things about Catholicism exist only in the minds of anti-Catholic fundamentalists who would rather believe the absolute worst with no evidence rather than do five minutes of research and find the truth, and who unfortunately spread this error along to other Christians who, though with no ill will, are neither sufficiently educated in Catholic history or hagiography to know the difference.

Phillip Campbell, “Virgin Mary Crucified,” Unam Sanctam Catholicam, Nov. 30, 2012. Available online at https://unamsanctamcatholicam.com/2023/04/virgin-mary-crucified