New Orleans has always been a cultural anomaly within the United States. Founded in 1718 by the Frenchman Jean Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville, the city remained under France until 1763 when it passed to Spain after the Seven Years’ War. Spain retained it until March 1803, when it was returned to the French until December 20, 1803, when the terms of the Louisiana Purchase translated it from French to American jurisdiction. With over a century of Franco-Spaniard Catholic heritage deeply embedded into the social fabric of the city prior to entering the Union, New Orleans would stand in stark contrast to the Anglo-derived culture that surrounded it in the American south.

Though blighted by the institution of slavery, French New Orleans boasted a higher population of free blacks than any other place in North America. Called gens de couleur libres (“free people of color”), they existed as a class of persons between whites and enslaved blacks. French law recognized their liberties in a body of legislation called the Code Noir, which guaranteed their right to own property, to access public education, enjoy full freedom of movement, and have recourse to the legal system. Most free blacks were former slaves who had been freed. The higher population of free blacks on French New Orleans relative to the rest of the South was due to the ease with which French law allowed manumission, compared to English law.

The population of free blacks grew exponentially under the Spaniards (1763-1803), whose manumission laws were even more lenient than the French and who permitted even slaves to own personal property and have access to education in the trades. The free black population grew 150% under Spanish rule due to Spanish policies which encouraged emancipation. (1) By the time New Orleans became American in 1803, it is estimated that 1/6 of the population were free people of color. (2) The Spaniards even armed and trained a free black militia of over 400 men; it fought with Bernardo de Galvez against the British in Florida during the American War of Independence. (3) The fact that educating and arming blacks was not only discouraged but illegal in the other southern colonies demonstrates how egalitarian New Orleanian society was for its time.

Black Catholicism in New Orleans

Given its century of Catholic culture under the French and Spanish, most blacks of New Orleans were Catholic, whether slave or free. Prior to entering the United States, black and white Catholics worshipped side by side in French New Orleans in integrated parishes. Catholic education was integrated as well. As early as 1724, the Ursuline nuns opened their educational facilities to black children.

After 1803, however, laws were introduced by the new American territorial government reducing the rights of free blacks, even to the point of requiring them to carry passes and observe curfews. Laws became increasingly severe in the decades leading up to the Civil War. Black Catholics subsequently found their educational opportunities compromised as the civil authorities and public opinion pressured the Church to abandon its commitment to integrated education. The Church—still French speaking and dominated by French clerics and French customs—tenaciously resisted American pressure to segregate, though not always successfully.

Some influential Catholics began to wonder if the solution could be found in separate black educational institutions. One such person was Ven. Henriette DeLille, a New Orleans free woman of color, who founded a teaching order called Sisters of the Holy Family dedicated to educating black children in New Orleans. (4) Ven. Henriette’s order was unique in that not only did it devote itself to the education of black children, but its sisters were drawn exclusively from the free black population, making it a black order (this was due to the difficulty of recruiting sisters from white orders to teach in black schools). Inspired by Ven. Henriette’s example, other white orders eventually came to New Orleans to assist the Holy Family sisters on a limited basis, creating a thriving “negro apostolate.” Ven. Henriette DeLille and her sisters nurtured the largest literate black community in the United States before the Civil War. (5)

The Third Council of Baltimore (1884)

In the years leading up to the Civil War, Catholic education in New Orleans was divided, as some clergy supported abolition and others sympathed with the Confederacy. This conflict is best exemplified by the hostility between popular abolitionist priest, Fr. Claude Paschal Maistre and Archbishop Jean-Marie Odin, a Confederate sympathizer. Yet, despite the support for slavery by certain members of the clergy, Masses were not segregated. Even Odin, a pro-Confederate, vehemently resisted pressure form other southern bishops to segregate New Orleans’ parishes. “Never had I seen such a mixture of conditions and colors,” one visitor reported in 1845 after visiting St. Louis Cathedral. (6) Though black and white Catholics worshiped side by side, other forms of racism from the colonial era endured—for example, in the refusal of the Church to ordain men of African descent.

After the defeat of the Confederacy, Archbishop Napoléon-Joseph Perché focused on expanding Catholic education throughout the archdiocese, erecting parishes and schools that were educating 11,000 Catholic children by 1888. Archbishop Napoléon-Joseph Perché was also attentive to the needs of black Catholic children, designating Fr. Antoine Borias to minister to them in particular.

This burst of school building was not unique to New Orleans. Catholic dioceses across the nation were rushing to construct parochial schools to compete with the boom of public schools being erected nationwide. Being generally poorer and less numerous than their Protestant counterparts, Catholic communities could seldom afford to fund parochial schools, and religious order schools generally suffered from understaffing, low enrollments, and rustic accomodations.

The problem of Catholic education was taken up by the Third Plenary Council of Baltimore, held in 1882 under the presidency of Archbishop (later Cardinal) James Gibbons of Baltimore. It is well-known that the Council of Baltimore provided the impetus for the erection of the parochial school system in the United States; Title VI of the Council’s acta proposed sweeping reforms to Catholic education, calling for every parish to have a corresponding parish school, mandating every Catholic parent send their children to them, and insisting that they be tuition free (i.e., subsidized 100% by the parish and/or diocese). What is less well-known is that the Council also resolved to establish separate facilities for black and white Catholics throughout the United States. The purpose of this was not to affirm existing racial biases, but rather to protect the Church in the United States. They knew that black parishioners in integrated parishes often faced neglect and discrimination and feared they would be preyed upon by Protestant missionaries seeking to exacerbate their dissatisfaction. They therefore decreed the erection of racially segregated parishes and schools and recommended bishops appoint priests whose sole duty was ministering to black Catholics, what was called the “negro apostolate.” The Council also recommended annual collections be taken up to fund Negro and Indian missions. (7)

The decision of the Council was not merely defensive. The bishops seemed to believe it would sincerely improve the faith life of black Catholics by giving them dedicated spaces and clergy. They also hoped that separate black parishes would attract black converts by mimicking a model that was being used successfully by most Protestant denominations after emancipation. (8) Thus, the Council Fathers’ support for segregated schools should not be construed as support of the white supremacist ideology driving the emergent Jim Crow laws; rather, the Council Fathers, recognizing the climate of racial hostility in the country, hoped segregated schools would facilitate better pastoral and educational care of black Catholics.

Archbishop Francis Janssens (1888-1897)

For most black Catholics throughout America, the policy of Baltimore had little effect. Separate parishes and schools were already prevalent, and the decrees of the Third Plenary Council simply reaffirmed existing practice. New Orleans, however, was a different matter. In this city where black Catholicism was largest and had its deepest historical roots, parishes and schools had traditionally been integrated. The new policy mandating segregated parishes thus violated ecclesiastical custom and offended prevailing social mores in the black community. The policy would provoke a prolonged resistance from New Orleans’ black Catholics that spanned several decades.

Archbishop Perché died the year before the Council, which was attended by his successor, Francis Xavier Leray. Leray held the see only briefly, from 1883 to 1887, but during that time he continued Perché’s program of building Catholic schools at an astonishing rate, increasing the number of parochial schools from 36 to 70 during his brief tenure. Being in poor health, however, Leray was not up to tackling the “negro apostolate” issue and made no attempt to segregate his parishes. Leray likely knew that his clergy—all ethnically French and French-speaking—would ardently resist Baltimore’s segregation decrees.

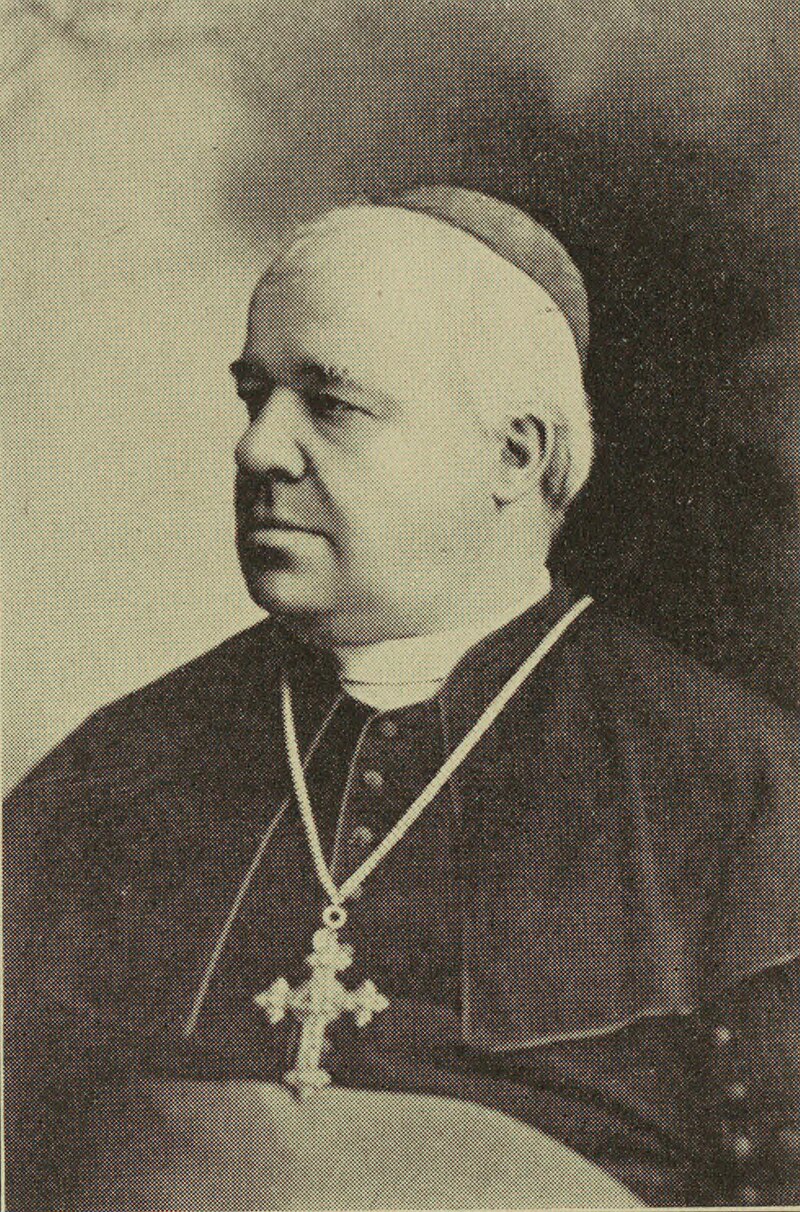

Leray’s death in 1887 was followed by the appoinment of the Dutch-born Francis Janssens as archbishop. Janssens was an associate of Archbishop Gibbons of Baltimore, having served as his vicar. He was also a former bishop of Natchez, Mississippi. Janssens’ appointment evoked protest and antipathy from the city’s clergy. For one thing, Janssens was a Dutch prelate presiding over a diocese of Frenchmen, holding an office traditionally held by a Frenchman, which alone was enough to upset the local clergy. (9) Furthermore, as a friend of Gibbons, he was an advocate for the decrees of Baltimore and had made a reputation in Natchez as an enforcer of parochial segregation. This was all alarming to the French clergy, who were resolved to ignore the segregation decrees of Baltimore as long as possible.

Before moving to impose segregation, Janssens restructured the finances of the diocese by incorporating every church parish within his diocese in 1889, a deal that required the approval the Louisiana state legislature. Though ostensibly done to help the archdiocese deal with its debt by distributing the burden across many financially independent parishes, the incorporation also gave Janssens more direct control over his parishes, recognized not just by canon law, but now reinforced by civil law.

This being accomplished, Janssens began his push to implement Baltimore’s decrees in New Orleans. This was a multi-faceted approach, geared not only towards segregating schools and parishes, but also towards “Americanizing” the clergy. He laid plans to open an English-speaking seminary to train native, English-speaking clergy. He also called for separate black parishes staffed by black priests, which he argued would foster a more vibrant black Catholic community.

The black Catholic population did not see it this way and reacted with anger and indignation to the archbishop’s plans. (10) But the most controvesial aspect of Janssens’ program related to parish schools. Despite the boom in school construction under Perché and Leray, the number of Catholic schools had still not kept pace with the explosion of the Catholic population, both black and white. Black Catholics were especially underrepresented. In 1890 there were only twelve dedicated black Catholic schools, with average enrollments of around seventy pupils. There were also a few private lay run black Catholic schools under clerical supervision, with enrollments around a dozen. It is estimated the total number of black Catholic pupils at the time of Janssens’ reforms was no greater than 1,000, out of a black Catholic popualtion of 60,000. (11). Black Catholics lobbied Janssens for more educational facilities; they even formed a protest group called “Justice,” whose aim was to pressure the archbishop for more facilities. Interestingly, one member of Justice was Homer A. Plessy, the shoemaker who would later be the plaintiff in the famous Supreme Court case Plessy v. Ferguson that legitimized segregated public facilities.

Janssens found himself in a difficult bind. New Orleans was in dire need of more Catholic schools across the board, as Baltimore had required every parish to manage a parochial school. This alone was a tremendous financial burden which Janssens struggled to lift, but which was compounded by the Council’s decree for segregated parishes, meaning, in effect, each parish required two schools. Furthermore, since Catholic education in those days was not co-ed, boys and girls were educated separately. Thus, each parish school called for by Baltmore really necessitated four facilities: a school for white boys and a school for white girls, and a school for black boys and a school for black girls. The obvious solution for a poor diocese would have been to merge, especially since there was a strong tradition of integrated education in New Orleans. But such would run afoul of the decrees of Baltimore. Janssens thus found himself in position where the very terms of what Balitmore commanded made them impossible to carry out.

Janssens did what he could to make ends meet. He obtained permission from the Vatican to allow religious sisters to teach post-pubsecent boys (something not generally permitted). He brought in the Holy Family Sisters to found a new school for black boys, and personally donated $200 to Mother Austin Carroll, R.S.M., Superior of the Sisters of Mercy for her new black Catholic school. But these endeavors, admirable as they were, provided support for only handfuls of students at a time, scarcely providing a suitable longterm solution.

Black Opposition

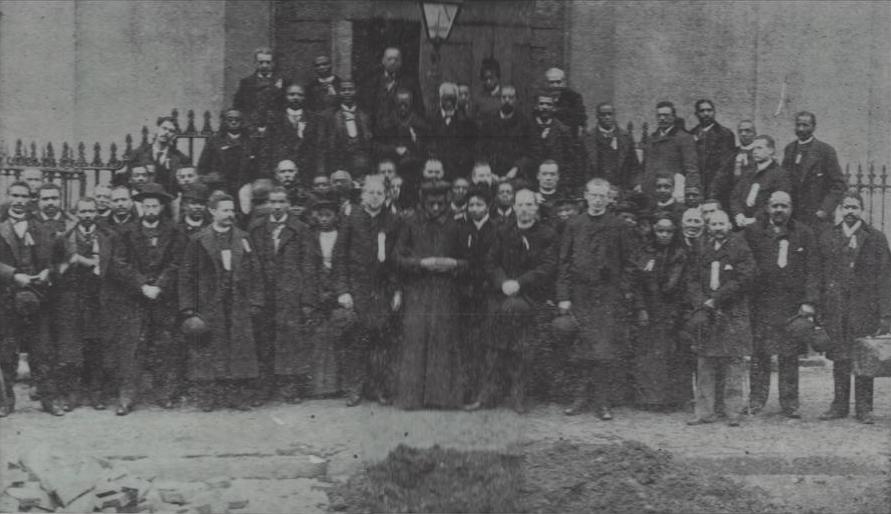

During this time, there was a call from African American Catholics across the United States calling for more black priests. These formed themselves into a movement and, under the auspices of the U.S. Catholic bishops, organized the Colored Catholic Congresses, national gatherings of black Catholics held between 1890 and 1894. These congresses were organized by Daniel Rudd, a black Catholic journalist who founded the Ohio Tribune and the American Catholic Tribune, both catering to a black readership and the latter which was the first nationally owned black Catholic newsaper. These congresses did not question the overall policy of dedicated black schools, but expressed anger and frustration over the insufficient number of secondary schools for black young men, and the Church’s insistence on racially segregated parishes. A particular grievance was Balitmore’s insistence on sending their children to Catholic schools when the Church did not provide enough of them. Whatever the hierarchy’s intentions were, the congress blasted them for accepting the color line, which was argued only increased discriminatory attitudes from the white laity. Ultimately, the Colored Catholic Congresses became too vocal in their critiques of the hierarchy and were shut down by the bishops in 1894. (12)

African Americans in New Orleans also resisted Janssens’ plans. There was such an outcry from black Catholics against segregated parishes that Janssens initially backed down in 1888. The opposition was strident as both black Catholics and French clergy resisted. This opposition stonewalled the bishop’s efforts for seven years; it was not until 1895 that Janssens finally got his segregated parish, and this by a twofold compromise: first, the proposed segregated parish would be located in the uptown district, far from the downtown integrated parishes, and thus unlikely to siphon black Catholics from the downtown parishes; second, it would be established as an “ethnic” or “national” parish, like earlier parishes set up for different immigrant nationalities. Membership in this parish would be voluntary, i.e., it would not be a segregated territorial parish that all black Catholics were required to attend.

Involvement of St. Katharine Drexel

Opposition of black Catholics and the French clergy weakened. All Janssens needed was funding, and this was provided by none other than the renowned St. Katharine Drexel of Philadelphia. St. Katharine was a wealthy heiress who had devoted a substantial sum of her late father’s inheritance to educating black Catholics and Indians. St. Katharine happily provided the necessary sum of $5,000. The new parish was named St. Katharine Church and dedicated on May 20, 1895. Ostensibly dedicated to the 3rd century martyr, the choice of name was in honor of the generosity of Mother Katharine. At the dedication of the parish, Archbishop Janssens said that the existence of a black parish was not in any meant “to convey the idea that there is a religion for the white people and one for the colored people.” Noting that there had been serious opposition to the church, he informed his listeners that it had been removed by his “earnest talk to these colored people, who were laboring under the mistaken idea that I intended to discriminate against them by opening this new church.” His intention was that Saint Katharine’s be a place where “the colored people will be at home. . . a church for their own special benefit and occupation.” None, however, would be compelled to attend it; all were free to remain in their own parishes. No matter what blacks chose to do, Janssens wanted them to know that Saint Katharine’s was “for them at all times.” (13)

Though attendance at the parish was not mandatory, Janssens seemed to hope black Catholics would gravitate there of their own accord, de facto segregating themselves. This did not happen. For one thing, most black Catholics lived downtown, far from St. Katharine’s uptown location on Tulane Avenue. If they walked there, they would pass multiple other integrated parishes on the way, making it unlikely they would travel so far for a segregated Mass. Second, the black community generally rejected the parish and boycotted it. Most of the parishioners of St. Katharine were not the old Catholic families, but converts from Protestantism brought in from the local neighborhood. St. Katharine Drexel herself was sharply criticized; one black newspaper lambasted her for her “misplaced bounty,” arguing that the consequence of her charity was that “the color-line is perpetuated where it exists already, and introduced with the germ of success where it has not been before.” (14) St. Katharine Drexel, who as a northerner did not understand the nuances of race relations in the Deep South nor the particular debates within the Archdiocese of New Orleans, was confused and hurt by the criticism. She vowed not to fund any more black parishes in New Orleans unless specifically requested to by black Catholics themselves.

St. Katharine’s parish remained as a primarily black parish until 1966, when it was destroyed by Hurricane Betsy and not rebuilt. During the fiftieth anniversary of its establishment in 1945, the Rev. Clarence Howard, S.V.D., himself a black priest, gave a talk on the special conditions behind the founding of the parish and the motivation of Archbishop Janssens. Fr. Howard said:

The white people during the course of years carried their personal prejudices into the church. The colored were segregated to the rear of the church. The colored began to stay away. Archbishop Janssens of New Orleans sought some way of making the situation better. He had as his example similar churches in Pittsburgh, Florida, Texas, and Baltimore, Maryland. However, he made it quite clear that he did not wish that people get the impression there was a religion for whites and a religion for colored. The colored people did not have to attend this church if they did not wish to do so. Very soon the colored saw it as a place where they might see their own boys serving on the altar, hear their own girls singing in the choir, and their husbands serving as ushers and leaders of religious organizations. (15)

Archbishop Placide Chapelle (1897-1905)

The French clergy of New Orleans had never been happy with the Dutchman Janssens. When Janssens died in 1897, they petitioned Rome directly for a Frenchman, specifically, Placide Louis Chapelle, then Archbishop of Santa Fe. The suffragan bishops of New Orleans opposed this, however, proposing a Belgian or Irish-born bishop to break the influence of the French lower clergy. The French clerics enlisted the aid of French President Félix Faure to pressure Leo XIII to appoint Chapelle. Pope Leo bowed to the pressure of Faure and the French and gave the clergy of New Orleans their French prelate, appointing Placide Chapelle on December 1, 1897. (16)

Like his French clergy, Chapelle disapproved of Janssens’ segregation program. He cancelled all of Janssens’ segregation programs and even closed Janssens’ fledgling English-language seminary. He diverted funds from the seminary to open a school for black children in the integrated parish of Lourdes.

Chapelle’s efforts to push back against segregation were drowned out in the flood of Jim Crow legislation that engulfed the South at the turn of the 20th century. Laws were passed effectively segregating every aspect of public life. The new Louisiana Constitution of 1898 implemented voting qualifications effectively disenfranchising black voters. (17) Meanwhile, at the federal level, Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) and Cumming v. School Board of Richmond County, Georgia (1899) enshrined de jure validated the legal principle of “separate but equal” facilities. Within New Orleans, the Robert Charles race riots of July 24-27, 1900, saw 28 people killed and 50 wounded, mostly blacks (the violence only ended when the riot’s namesake, Robert Charles, wanted for the murder of a police officer, was killed, shot over a hundred times by a mob). (18) These events convinced most black leaders that resistance to the new regime would only make things worse.

Despite these sad developments, Archbishop Chapelle steadfastly resisted calls to segregate New Orleans’ parishes. This must have taken extraordinary courage on the part of Chapelle, as pressure was brought to bear upon him from the civil authorities, from the white populace, from his suffragan bishops, and from Cardinal Gibbons and the authority of the Third Council of Baltimore. Despite this, Chapelle took no action, and New Orleans’ parishes remained integrated. Unfortunately, Chapelle’s latter years were consumed with diplomatic work as he was appointed Apostolic Delegate to Cuba in the wake of the Spanish-American War, followed by similar appointments to Puerto Rico and the Philippines in 1899. He eventually caught yellow fever and died in 1905.

Archbishop James Hubert Blenk (1906-1917)

Chapelle was replaced by James Hubert Blenk, a German from the Rhineland who had formerly served as Bishop of Puerto Rico. Despite being ordained by Chapelle, Blenk was a supporter of the Third Plenary Council of Baltimore and returned to Janssens’ program of segregation. Blenk insisted that every parish have its own parochial school, paid for by parishioners and under the authority of the pastor. He also invited in the Dominican Sisters to found the Dominican College to train women teachers, both religious and lay, to teach in New Orleans’ burgeoning parochial school system. The Dominican College was up and running by December, 1909.

As discussed above, since Catholic schools were gender-segregated—and since white parents often refused to send their children to integrated schools—the decrees of Baltimore practically entailed the creation of four institutes per parish, one school for white boys and another for white girls, along with a third school for black boys and a fourth for black girls. But as parishioners could scarcely afford even one school, generally white education was prioritized and black Catholics simply went with no schools whatsoever.

Blenk was not oblivious to this difficulty, and he particularly feared losing black Catholics to Protestant churches, who were actively poaching them by promising exclusive black churches and educational facilities. Blenk knew he had to find some way to establish black parishes with dedicated black parochial schools. He opened a school for St. Katharine’s in 1907, which attracted students from all over due to its status as a non-territorial “national” parish. Unfortunately, Blenk could not replicate the success of St. Katharine’s school, as Rome was increasingly hostile to national parishes, which they believed undermined the universality of the Church.

Blenk set about collecting money from various places, including the Drexel family, the Commission for Catholic Missions Among Colored People and Indians, and the Catholic Board for Mission Work Among the Colored People, the latter of which counted Blenk among its board members. With enough money on hand, Blenk recruited the Josephite Fathers out of Palmetto, LA to help him launch New Orleans’ “negro apostolate.”

The Josephite Fathers

The Josephite Fathers would be pivotal in executing Blenk’s vision. For example, in 1909, Blenk established a segregated territorial parish after the parishioners of Mater Dolorosa (which had until that time been intregrated) voted to exclude black Catholics from their parish, which had just moved into new facilities. Blenk asked the Josephite Fr. Peter O. LeBeau to attend to the abandoned black Catholics of Mater Dolorosa. Fr. LeBeau organized purchased a building that had once been a school run by the Sisters of the Holy Family and converted it into a church. This became St. Dominic’s, the first territorial segregated parish in New Orleans. St. Dominic’s would be a resounding success. Fr. LeBeau was able to expand the parochial school and pay off the parish’s debt by 1912. Following the success of St. Dominic, Archbishop Blenk asked the Josephites to assume direction of the entire black Catholic ministry in the city.

Education was still a pressing need in the black Catholic community by the eve of World War I. Many of the small black schools had closed by 1914, the number of foreign born religious willing to teach black Catholic children declined, and white hostility militated against devoting resources to black education. Multiple parochial schools closed their doors to black students between 1890 and 1914. Though this was sometimes due to blatant racial hostility, it was just as often a financial calculus. For example, in 1911, the integrated St. Rose of Lima parish raised sufficient funds to build two schools, choosing to build one for white boys, and one for white girls. Many black Catholic families opted to send their children to public schools. This was not ideal and actually forbidden by the decrees of the Council of Balitmore, but necessity left them little choice. The only black secondary school left in New Orleans by World War I was run by the Holy Family Sisters, but their rules prohibited them from teaching boys past puberty, meaning black adolescent boys were the especially underserved.

Fr. LeBeau conferred with his superior, Fr. Justin McCarthy, to fill the need for higher education for black Catholic adolscents. They came up with a plan for Mother Katharine Drexel to purchase the old facilities of Southern University, a former black college in New Orleans that had recently relocated to Baton Rouge. The building would become a college for black Catholic men named Xavier University. The Josephites presented the plan to Blenk and St. Katharine Drexel, who were both enthusiastic. The building was purchased by St. Katharine in 1915 for $18,000. The facilities were so spacious that the auditorium of the school was separated and given to the archdiocese to establish another segregated Josephite parish. This became Blessed Sacrament. Blessed Sacrament parish and Xavier University were opened to much fanfare in 1915. Both are still functioning today (although Blessed Sacrament has been merged with the former St. Dominic, and is now known as Blessed Sacrament-St. Joan of Arc parish).

Sadly, Fr. LeBeau died of illness soon after Xavier’s opening. He was replaced by the Josephite Fr. Samuel Kelly of Pennsylvania. Kelly had long dreamed of opening a black Catholic parish in the Seventh Ward, the heart of New Orleans’ historic black district. Again with the financial assistance of St. Katharine Drexel, he established Corpus Christi Parish and School near the intersection of N. Johnson and Onzaga Street. The founding of Corpus Christi was not without difficulty. Black Catholics downtown were among the oldest black Catholic families in the city and fiercely resisted attempts to segregate them. Fr. Kelly gradually won them over, however, partially due to his personal charisma and extensive experience with black Catholics, partially by appeal to the cold reality of the situation: the gravest need in the black Catholic community was access to black schools. As these schools would not be erected outside a parochial structure, black Catholics simply needed to accept segregated parishes as a means to obtaining access to Catholic education.

Corpus Christi would be the most successful of Archbishop Blenk’s segregated parishes. Erected in 1916, within a year the parish school had 600 students, compared to 159 in St. Dominic and 100 in Blessed Sacrament during the same period; Corpus Christi would eventually swell to 1,273 students by 1929 (19). Within only a few months of opening, Corpus Christi had three times the parishioners registered as the other two parishes combined. This speaks to the numbers and vitality of black Catholics in New Orleans’ downtown district.

The years between the end of World War I and the outbreak of the Great Depression saw the activity of the Josephites increase dramatically. This was in part due to the demise of French influence in the New Orleans Archdiocese. The French clergy had always objected to segregation, but when World War I broke out, native French priests were recalled back to France; few returned after the war’s end. This meant an effective end to any internal opposition to segregation within the archdiocese, and the Josephites stepped in to fill the space vacated by the French priests. Furthermore, the Josephites were simply very successful at parish building. Four additional segregated parishes were constructed between 1919 and 1929 (Holy Redeemer, All Saints, Peter Claver, St. Raymond), as well as an addition to the already overcrowded Corpus Christi, all staffed by Josephites.

These segregated Josephite parishes were extremely successful in every respect. They attracted enough families to remain fiscally solvent, their schools were full, and the ministerial needs of black Catholics were being met. Even so, black Catholics in New Orleans were not happy with their segregated status. It’s fair to say segregation was not happily accepted anywhere by blacks, but this was especially the case in New Orleans where there was a prior history of integration that many black Catholics in the 1920s were well old enough to remember. As World War I drew to a close, black Catholics in New Orleans founded the Federation of Catholic Societies for the Colored People of the Gulf States as an umbrella organization for the various Catholic movements opposing segregation in southern Catholic parishes. (20) Such endeavors were supported by national organizations with similar aims, such as the Committee Against the Extension of Racial Prejudice in the (Catholic) Church, founded in Washington D.C. in 1919 by black civil rights activist and biologist Thomas Wyatt Turner (21). Turner’s organization was later renamed the Committee for the Advancement of Colored Catholics. These organizations argued that the Catholic Church was adopting a Protestant approach to race and argued that racially segregated parishes violated canon law.

The Josephites in particular were attacked by these organizations as perpetrators of “the color line” into the Catholic Church. The Josephites believed these criticisms were unfair. They had come into the Archdiocese of New Orleans at a time when black Catholics had little spiritual or educational opportunities and worked diligently to serve them within the social conditions as they found them. Facing prolonged criticisms from black Catholic organizations, the Josephite priest Fr. John T. Gillard authored a lengthy rebuttal in his 1929 book The Catholic Church and the American Negro, published by Josephite Press. Gillard not only defended the Josephite’s missionary work, but offered a robust defense of segregation within the Church as a solution to what he called “the race problem.” (22)

Coming out as it did in 1929, Fr. Gillard’s spirited defense of segregation struck many American Catholic readers as anachronistic, for even as New Orleans had succeeded in erecting a fully segregated black parochial system, Catholics in the rest of the country were beginning to look more critically at segregation. This was part of a larger social awareness brewing in the clergy of the 1930s, in light of which the policies of New Orleans (and the Church in the south in general) seemed out of place. Fr. Gillard’s The Catholic Church and the American Negro would provoke a national dialogue among American Catholics throughout the thirties on the question of segregation within Catholic parishes.

The End of an Era

While discussions about segregation would continue, the Josephite work in New Orleans slowed with the outset of the Great Depression in 1929, simply due to the fact that the economic hardship made further building an expansion untenable. A few segregated parishes continued to be erected under Archbishop Joseph Rummel into the 1930s; the Josephites managed to erect a segregated parish in New Orleans as late as 1949, St. Philip the Apostle parish. By that time, however, pressure for integration was so strong that the Church could not longer resist, and Archbishop Rummel ordered the desegregation of New Orleans’ parishes and schools in 1950.

The story of segregated parishes in the Archdiocese of New Orleans is fascinating and complex, such that we cannot possibly do it justice with this article, long though it is. There are a few things we can say in summation, however:

1) Segregation was introduced into Catholic parishes not because of racial hostility on the part of the hierarchy, but as a means of “protecting” black Catholics from the neglect they were wont to receive in integrated parishes. It was seen as a means of ministering to their needs more effectively in light of the social movement towards segrgation across the country.

2) Segregation was vehemently resisted by French-speaking clergy, as well as by black Catholics themselves, who, at least in New Orleans, had been accustomed to integrated parishes.

3) In the erection of segregated parishes, it was the need for access to Catholic education that preceded the establishment of churches, not vice versa.

4) St. Katharine Drexel and her Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament were instrumental in funding the erection of the first black parishes while the Josphites took up the work of staffing them through the first half of the twentieth century.

5) Though black Catholics resisted segregated parishes in a variety of ways, once established, these parishes were very successful by every measurable metric.

Before concluding, I’d like to acknowledge the work of John B. Alberts in his article “Black Catholic Schools: The Josephite Parishes During the Jim Crow Era” (U.S. Catholic Historian, Vol 12, No. 1, Winter 1994) for the basic outline of events followed by this article.

Before You Go…

Finally, if you find this sort of content valuable and edifying, please consider making a financial contribution to this website. We run no advertisements and accept no sponsorships, so it is entirely through the contirbutions of generous readers that this site is maintained. Your contribution helps free up to the time necessary to research and create more such essays on Catholic history. Use this Paypal link to make a secure donation, one time or recurring (Please note, donations will show as being made to Cruachan Hill Press, the company which owns the Unam Sanctam Catholicam website).

(1) Elizabeth Clark Niedenbach, “Free People of Color in Colonial Louisiana,” 64 Parishes, Nov. 8. 2022. Available online at https://64parishes.org/entry/free-people-of-color-in-colonial-louisiana-adaptation

(2) Michael Taylor, “Free People of Color in Colonial Louisiana,” LSU Libraries, Available online at https://lib.lsu.edu/sites/all/files/sc/fpoc/history.html

(3) See Niedenach. Also see, Erick Trickey, “The Little-Remembered Ally Who Helped America Win the Revolution” Smithsonian Magazine, Jan. 13, 2017. Available online at https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/little-remembered-ally-who-helped-america-win-revolution-180961782/

(4) “Brief History of the Sisters of the Holy Family,” available online at https://www.sistersoftheholyfamily.com/who%20we%20are

(5) John B. Alberts, “Black Catholic Schools: The Josephite Parishes of New Orleans During the Jim Crow Era,” U.S. Catholic Historian Vol. 12, No. 1, Winter 1994 (Our Sunday Visitor: Huntington, IN.), 77

(6) Michael Tisserand, “A Priest on the Color Line.” 64 Parishes. Available online at https://64parishes.org/a-priest-on-the-color-line

(7) Alberts, 78

(8) Edward Misch, “The Catholic Church and the Negro, 1865-1884,” Integrated Education 72 (Nov.-Dec. 1974), 36-38.

(9) As reported in Morning Star, July 7, 1888, quoted in Roger Baudier, The Catholic Church in Louisiana (New Orleans, 1935), 497

(10) Sr. M. Florita Lee, “The Efforts of the Archbishop of New Orleans to Put into Effect the Recommendations of the Second and Third Councils of Baltimore with Regard to Catholic Education, 1860-1917,” (M.A. Thesis, Catholic University of America, 1946), pp. 71, 82

(11) Roger Baudier, Centennial, 1857-1957: St. Rose de Lima Parish (New Orleans, 1957), 34

(12) Alberts, 82

(13) Janssens’ comments from Douglas Slawson, C.M., “Segregated Catholicism: The Origin of St. Katharine’s Parish, New Orleans,” Vincentian Heritage Journal, Vol. 17, No. 13, Fall , 1996, pp. 171-172

(14) Alberts, 84

(15) “The Old Timers: St. Katherine’s Golden Anniversary Celebration,” The Louisiana Weekly, Oct. 6, 1945, pp. 9, 12. Available online at https://www.creolegen.org/

2012/11/01/the-old-timers-st-katherines-50th-anniversary-celebration-1945/

(16) See “CHAPELLE IS NAMED,” The Assumption Pioneer, Napoleonville, LA. December 4, 1897 and “NEW FIELD OF LABOR: Archbishop Chapelle to Take Charge of the New Orleans Diocese,” Las Vegas Daily Optic, November 29, 1897.

(17) See Louisiana Constitution of 1898, Art. 197-198

(18) William Ivy Hair, Carnival of Fury: Robert Charles and the New Orleans Race Riot of 1900 (Louisiana State University Press: Baton Rouge, 1976), pp. 170-171

(19) Alberts, 92

(20) Ronald Sharps, “Black Catholics in the United States: A Historical Chronology.” U.S. Catholic Historian, Vol. 12, No. 1, African-American Catholics and Their Church (Winter, 1994), p. 128

(21) Ibid.”

(22) The Catholic Church and the American Negro John T. Gillard Review Catherine A. Caraher, in Records of the American Catholic Historical Society of Philadelphia, Vol. 80, No. 4 (Dec. 1969), 244-247

Phillip Campbell, “Segregated Catholic Schools in New Orleans,” Unam Sanctam Catholicam, Dec. 31, 2023. Available online at https://unamsanctamcatholicam.com/2023/12/segregated-catholic-schools-in-new-orleans