The 14th century in England saw the flowering of Middle English literature. Beginning with classics like Sir Gawain and the Green Knight and Piers Plowman, the literary world of the 1300s blossomed with the mystical writings of Julian or Norwich, Richard Rolle, and Margery Kempe, and culminated with Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales at the close of the century. It was truly a golden age of Middle English poetry and prose.

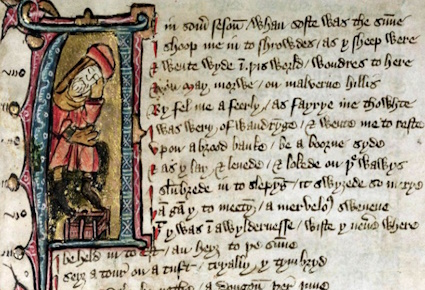

One of the most interesting poems of the era is St. Erkenwald, believed to have been composed sometime around 1380-1390. St. Erkenwald is an alliterative poem, meaning it makes generous use of alliteration to give it metrical structure (alliteration is the repetition of sounds among nearby words, such as “Peter Piper picked a peck of pickled peppers”). Set anachronistically in 7th century London during the episcopacy of St. Erkenwald (sometimes spelled Erconwald), the poem deals with St. Erkenwald’s conversation with a reanimated corpse. The author is unknown, although scholars suspect he is the same poet who wrote Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. Philologists E.V. Gordon and J.R.R. Tolkien studied the text in 1925. Of the author, Tolkien said—

He was a man of serious and devout mind, though not without humour; he had an interest in theology, and some knowledge of it, though an amateur knowledge perhaps, rather than a professional; he had Latin and French and was well enough read in French books, both romantic and instructive; but his home was in the West Midlands of England; so much his language shows, and his metre, and his scenery. (1)

St. Erkenwald survives only in a single manuscript, Harvey 2250 kept in the British Museum. It was discovered in 1757 by the antiquarian Anglican Bishop Thomas Percy of Dromore, County Down, Ireland.

The Plot of St. Erkenwald

The poem uses a fictional dialogue between St. Erkenwald and a resuscitated corpse to explore the question of the salvation of righteous pagans. The historical St. Erkenwald was Bishop of London from 675-693, corresponding with the reigns of the Anglo-Saxon kings Sighere and Saebbi of Essex. (2) The miracle related in the poem does not occur in the 12th century hagiography Miracula Sanct Erkenwaldi and is therefore presumed to be freely invented by the poet as a literary device through which to explore the question of the salvation of righteous pagans.

The poem begins with a brief account of the conversion of Britain and moves on to the episcopacy of Erkenwald and the construction of St. Paul’s Cathedral. According to the poem, St. Paul’s was constructed upon an old pagan temple called the Triapolitan (there is no consensus on what this word means). During the construction, workers digging into the floor find a corpse from pre-Christian times that is miraculously incorrupt.

Marveling at the miraculous preservation of the corpse, Erkenwald celebrates Mass and then commands the corpse to speak in the name of Jesus Christ. The corpse comes alive and identifies itself as a prominent judge from the reign of King Belinus, a legendary pre-Saxon monarch supposed to have reigned around the year 390 B.C. (For those unfamiliar with medieval English historiography, the medieval English believed themselves to be descendants of Trojans through the eponymous Brutus of Troy, son of Silvius Postumus, grandson of Aeneas. This is why there are references to Troy and Trojans in the poem; Belinus is of the Bruttian line).

After hearing of the judge’s virtuous conduct in office, St. Erkenwald assumes the man must have gone to heaven. He says:

He who rewards each man as he has served justice could scarcely ignore to give some branch of His grace. For as he says in his true psalm written: ‘the righteous and the spiritually pure come always to me. ‘ Therefore, tell me of your soul, where she resides in bliss, and of the noble restoration that our Lord handed to her.” (3)

The corpse, however, explains that he had been damned to hell because he was born a pagan and never heard the saving words of Christ. He mentions being left behind at the Harrowing of Hell. Addressing Christ, he says, “when You took your remnant out of limbo, You left me” (4).

St. Erkenwald is moved to tears by the man’s story and wishes to fetch water to baptize him while he is yet conscious. The corpse, however, tells St. Erkenwald that as soon as the saint’s tears fell upon his face, his soul was saved, the bishop’s tears serving as the water of baptism. Now enjoying the bliss of heaven, the judge’s body instantly turns to dust.

Theological Considerations

St. Erkenwald is clearly meant to address the question of the salvation of righteous pagans, falling into the same genre as the legend of Pope Gregory and Trajan, and the story of Thecla and Falconella from The Acts of Paul and Thecla. Medieval Christians struggled to understand how the eternal destiny of righteous pagans fit into God’s providence just as much as Christians today; St. Erkenwald is a reflection of this question’s perennial interest.

Understood strictly as theology, the story is difficult to square. Commentators are divided on whether the judge was in hell proper or limbo. For the story to make sense within an orthodox theological framework, the judge would have to be in the limbo of the fathers; yet the text affirms he is in “the pit of hell” (the Middle English literally says “helle-hole”). The poem also says the souls of those saved at the Harrowing of Hell were taken “oute of limbo,” so clearly the poet could have designated the judge as being in limbo if he so wished, yet took pains to establish that he is in “helle-hole,” not limbo. (5)

Furthermore, if the judge was as righteous as he says—and the poem clearly wants us to believe he is—then why was he left behind at the Harrowing of Hell? The poem affirms that some righteous souls before Christ were in fact saved from damnation on Holy Saturday; if so, why was the righteous judge excluded?

The physical resuscitation of the judge is what makes St. Erkenwald’s baptism and the judge’s salvation possible, as one must be physically alive to be the subject of water baptism. Erkenwald’s tears serve as baptismal water:

With grief the bishop turned down his eyes; he had no opportunity to speak, so he quickly sobbed until he took a pause and looked with cleansing tears to the tomb, to the body where it lay. “Our Lord grant,” said that man, “that you would have life by God’s leave, long enough that I might get water, and cast it upon you, fair corpse, and speak these words, ‘I baptize you in the Father’s name and his noble Child’s and of the gracious Holy Ghost, and not a moment longer. Then, even though you dropped down dead, it would endanger me little.”

With that word he spoke, the wetness of his eyes and tears streamed down and landed in the tomb, and one fell on the face, and the man sighed. Then he said with a sad sound: “Our Saviour be praised! Now praised be You, exalted God, and Your gracious Mother…Through the words that you spoke and the water that you shed, the shining stream of your eyes, my baptism is attained. The first drop that fell on me diminished all my grief to nothing; right now my soul is placed at the table to supper. For with the words and the water that cleansed us of pain, softly flashed in the abyss of Hell below a ray of light which immediately caused my spirit to leap with unrestrained reIigious joy into the Upper Room where all the faithful ones eat supper solemnly; and there with honor greatest of all a marshall greeted her [the soul], and with reverence he gave a room to her forever. I therefore praise my high God, and also you, bishop, who have brought us from anguish to bliss, blessed are you!” (6)

Setting aside the fact that Erkenwald’s baptismal formula leaves much to be desired, we may wonder how a soul that had endured, by his own account, “a thousand and thirty and threefold eight years” (i.e., one thousand fifty four years) under a sentence of damnation could have the finality of his damnation overruled. The poem makes it clear that, though the body is reanimated and allowed to speak, its soul never leaves hell, and so we can question whether the judge has truly been raised from the dead, since there is not a proper reunification of soul and body—yet, if the judge has not been truly resurrected, in what sense can he receive baptism?

All this is a round about way of saying that, theologically, the poem is inconsitent and asystematic. We should not, however, miss the forest for the trees. While the theology of St. Erkenwald might not make sense, there’s no reason it needs to; it’s a work of historical fiction loosely centered on the life of an ancient bishop for the purpose of communicating an idea—the idea being that we can trust the justice of God; that those who belong there will find their way there by God’s assistance; even in ways we can neither predict nor understand; that God’s mercy triumphs over judgment (c. Jas. 2:13). It is also noteworthy that, when he hears of the judge’s righteous life, St. Erkenwald confidently assumes he has attained salvation. Though Erkenwald at first appears incorrect, his assumption about God’s design to save the man ends up being vindicated in the end.

Below I have included the full text of St Erkenwald translated into modern English (although the translation does away with the alliteration, so its poetic quality can no longer be discerned). Whatever we may think of the theology behind the Erkenwald poem, we can nevertheless acknowledge it as an exemplar of Middle English pietistical literature at its peak, as well as a testimony to the theological problems 14th century Christians grappled with.

I. St. Augustine Overthrows the Demons of the Saxons

In London, England, not very long after Christ suffered on the cross and established Christianity, there was a blessed and consecrated bishop in the city; I believe that holy man was called St. Erkenwald. In his time, the greatest of all temples in that town was pulled down—one part of it—to be dedicated anew, for it had been a heathen temple in the days of Hengest whom the warlike Saxons had sent here. They beat out the Britons and brought them into Wales and perverted all the people who dwelt in that place. It was then that this kingdom renounced its religion for many rebellious years until St. Augustine was sent into Sandwich by the Pope. Then he preached the pure faith here and planted the truth, and converted all the communities to Christianity again. He changed the nature of temples that at that time belonged to the devil and cleansed them in Christ’s name and called them churches; he hurled out their idols and brought in saints, and he first changed their names and bound them by oath for the better; what was Apollo before now was Saint Peter, Mahomet was changed to St. Margaret or St. Mary Magdalene. The pagan temple of the sun was assigned to Our Lady, Jupiter and Juno to Jesus or James. So he rededicated all that had before been assigned to Satan in Saxon times to honored saints.

II. An Incorrupt Corpse Discovered Under St. Paul’s Cathedral

What is now named London had been called the New Troy, and it evermore has been the metropolis and the master town. A mighty devil owned a great pagan temple therein, and the title assigned to the temple was his name, for he was the most honorable lord of idols praised and his sacrifice was the most solemn in pagan lands. His was the third temple reckoned to be in the Triapolitan: only two others were within all Britain’s coasts. Now Erkenwald, who teaches law in beloved London-town, is the bishop of this Augustinian province; he presides with fitting demeanor in the episcopal office of the St. Paul cathedral that was [once] the temple Triapolitan as I told previously. At that time, it was demolished and beaten down and built new again, a noble business in this particular instance, and it was called the New Work. Many merry masons were compelled to work there, cutting hard stones with sharp edged tools. Many diggers of the earth searched the ground to find the firstlaid foundation still firm on its footing. As they worked and mined, they discovered a marvel of which the memory is still made known in the keenest of chronicles, for as they created and dug so deeply into the earth, they found a wonderfully beautiful tomb built on a floor; it was a coffin of thick stone excellently cut with gargoyles decorating all of the gray marble. The bar of the tomb that locked it on top was properly made of the marble and gracefully smoothed, and the border was decorated with bright gold letters, but the rows of sentences that stood there were mysterious. The characters were very precise, and many observed them and pondered out loud about what they could signify. Many priests with very broad tonsures in that cathedral busied themselves but were unable to bring the letters to words. When tidings of the tomb-wonder took to the town, many hundreds of worthy men hurried to the tomb at once; craftsmen, heralds, and others followed as well as many craft

guild members of diverse trades; youths left their work and leaped in that direction, running quickly in a disorderly crowd ringing with noise; many people of every kind came there so quickly that it was as if the world were gathered there within an instant. When the mayor with his retainers, who by assent of the sexton guarded the area around the altar, caught sight of that marvel, he requested that they unlock the lid and lay it beside the coffin; they would look on that vessel to see what dwelt within. With that, strong workmen went to it, applied levers to it, pinched one under, caught the corners with iron crowbars and, although the lid was very large, they laid it by the coffin soon. Then the men who stood about and could not understand such strange cleverness were bestowed with an abundance of wonder. The bright spot within was so beautiful, all painted with gold, and a blissful body, arrayed in a luxurious manner in royal clothing, lay upon the bottom. His gown was hemmed with glistening gold, with many precious pearls set there, and a girdle of gold encircled his waist; a large gown was trimmed on top with miniver fur, the cloth of very well made wool and silk with handsome borders; and a very ornate crown was placed on his close-fitting headdress and a dignified scepter was placed in his hand. His clothes were without any flaw, stain, or blemish; neither were they moldy, spotted, or motheaten. And they were bright with shining colors as if they had been closed in that casket just yesterday. And fresh was his face and so was the naked flesh by his ears and hands that visibly showed with a proud red, like that of the rose and his two red lips, as if he were in sound health and suddenly had fallen asleep. There was a profitless interval of time in which men asked each other what body it might be that was buried there. How long had he lain there, his face so unchanged, and all his clothing unspoiled? This every man asked.

III. St. Erkenwald is Told of the Prodigy

“But such a man as this should stand long in the memory,” said the on-lookers. “It seems obvious he has been king of this place, yet he lies buried this deep; it is an astonishing wonder that a man can not say he has seen him.” But all this meant nothing, for none could claim from any inscription or symbol, or from any tale that was ever written down in that city or noted in a book, that such a man, either highborn or low, was remembered. In a while, the message of that buried body and all its marvelous wonder was brought to the bishop. The primate, Sir Erkenwald, with his prelacy, was away from home, visiting an abbey in Essex. Men told him the tale of trouble among the people and that such a cry about a corpse was spoken loudly again and again; the bishop sent heralds and letters to put an end to the uproar and hastened to London soon afterward on his horse.

IV. The Prayers of St. Erkenwald

By the time that [Erkenwald] came to the well-known church of St. Paul, on that landmark, he met many people who, with a mighty clamor, told him of the marvel. He ordered silence, and, staying away from the dead one, calmly passed into his bishop’s palace and closed the door after him. The dark night passed away and the day-bell rang, and Sir Erkenwald, who had recited his prayers all night, was up in the pre-dawn before then to implore his Sovereign of His sweet grace to vouchsafe to reveaI the identity of the corpse to him by a vision or something else. “Though I am unworthy,” he said weeping, “may my Lord grant this through His noble humility: in confirmation of Your Christian faith help me to explain the mystery of this marvel tha t men wonder openly about.” And he begged for grace so long that he had a favor granted, an answer from the Holy Ghost, and afterwards dawn came.

V. Erkenwald Says Mass and is Shown the Corpse

Cathedral doors were opened when the first of the canonical prayers were sung; the bishop solemnly prepared himself to sing the high mass. The prelate in his bishop’s vestments was dressed in priestlike fashion. With his ministers, he properly began the mass of the Holy Spirit, for his assistance in a wise manner, and the pleasant voices of the choir burst into song with very beautiful notes. Many great, richly dressed lords were gathered to hear it—the most elegant of the realm went there often—until the service was ended and the concluding part was said; then all of the high company proceeded from the altar. The prelate passed on to the open space, and there the lords bowed to him. Richly dressed in ecclesiastical garments, he proceeded to the tomb. Men unlocked the enclosed area for him with clustered keys, but the throng that passed after him was troubled of mind. The bishop came to the tomb with his barons beside him, the mayor with many mighty men and mace bearers before him. The dean of the beloved place first described everything, pointing to the strange finding with his finger. “Behold, lords,” said the man, “such a corpse is here that has lain locked up below, how long is unknown; and yet his color and his clothing have caught no damage, nor his flesh nor the vessel he has lain in. There is no man alive who has lived so long that he can remember in his mind that such a man reigned, or speak of either his name or his reputation; although many poorer men are put into the grave in this place, they are recorded in our burial register and remembered forever; and we have searched through our library these long seven days, but we could never find one chronicle of this king. To look at his nature, he has not lain here long enough yet to have passed away so out of memory—unless something extraordinary has occurred.”

“You speak the truth,” said the man who was a consecrated bishop. “It is a marvel to men that comes to a trifle in comparison with the providence of the Prince who rules paradise when it is pleasing to Him to unlock the least of his powers. But when man’s might is rendered helpless and his mind surpassed, and all his thinking faculties are destroyed and he stands without resources of wisdom, then it hinders Him very little to loose with a finger what all the hands under heaven never might. Whereas when man’s skill of wisdom fails, he requires the attention and spiritual comfort of the Creator. And so we should now do our deed, and engage in speculation no further. As you see, we receive no benefit seeking the truth by ourselves; but we all openly rejoice in God and ask His grace, who is generous to send counsel and comfort, and does that in confirmation of your faith and true belief. I shall inform you so truly of His virtues that you may forever believe that He is Lord almighty and trust your desires will be fulfilled if you believe Him a friend.”

VI. St. Erkenwald Causes the Corpse to Speak

Then he turns to the tomb and talks to the corpse; lifting up his eyelids, he set free such words: “Now corpse that you are, lying there, lie you no longer! Since Jesus has determined to make manifest his joy today, be obedient to his commandment, I bid on his behalf; as He was bound on the Cross when he shed his blood, as you [the dead] certainly know and we [the living] can only believe, answer here to my command and conceal no truth! Since we know not who you are, inform us of what world you were and why you lie thus, how long have lain here and what law you used, whether you are joined to joy or judged to damnation.” When the man had said this and thereafter sighed, the bright body in the tomb moved a little, and he forced out words speaking mournfully through some spirit-life lent by Him who governs all. “Bishop,” said this same body, “I hold your command in high regard; I can only submit to your command, even if I were to lose both my eyes as a result. All heaven and hell and earth between hold to the name that you have mentioned and called me in the name of.

VII. The Corpse Reveals His Identity

First, to tell the truth about who I was: one of the unluckiest men who ever on earth went, not a king nor emperor nor even knight, but a man of the law that the land then used. I was put in charge and made a leader here to judge trials; I had charge of this city under a prince of rank of pagan’s law, and each man who followed him believed in the same faith. I have been lying here for an incalculable period; it is too much for any man to calculate. After Brutus first built this city, it was not but eighteen years lacking from five hundred before your Christ was conceived by Christian account: a thousand and thirty and threefold eight years [1054]. I was of eyre and of oyer [i.e., a high ranking judge] in the New Troy in the reign of the noble king who ruled us then, the bold Britain Sir Belinus—Sir Brennius was his brother! Many insults were hurled between them in their ruinous warfare while their wrath lasted. It was then that I was appointed judge here in noble pagan law.” While he spoke from the tomb, there sprang from the people no word for all the world, no sound arose, but all were as still as stone as they stood and listened with much unsettled wonder, and very many wept.

VIII. The Corpse Tells of His Virtuous Life

The bishop bade that body, “Reveal your reason, since you were not known as a king, why you wear the crown. Why do you hold the scepter so high in your hand? You had no land or vassals or control of life and limb?” “Dear sir,” said the dead body, “I intend to tell you, as it was never my will that brought about this as it were. I was deputy and principal judge under a noble duke and this place was put altogether in my power. I governed this proud town in a noble manner, and always in an attitude of good faith, for more than forty winters. The people were wicked, deceitful, and perverse to rule—I suffered harms very often to hold them to what is just; but for no danger or riches, for no anger or fear, for no power or reward or fear of any man, did I ever depart from the right, according to my own reasoning. I never delivered a wrong judgement on any day of my life, nor diverted my conscience for any kind of avarice on earth, nor made any crafty judgements, nor committed any frauds for the sake of deference no matter how noble a man may have been; neither man’s threats nor mischief nor remorse moved me from the high path to deviate from what is right in so far as my faith regulated my conscience. Though it had been my father’s murderer, offered him no wrong, nor false favors to my father, though it fell to him to be hanged. Because I was righteous, upright, and quick of the law, when died sorrow filled all Troy with confused noise; all lamented my death, the greater and the lesser ones, and thus to my honor they buried my body in gold, dressed me in the most refined clothing that the court was able to hold, in a long gown for the most compassionate and manliest one on the judicial bench; I they girded me as the most skilled and competent governor of Troy, furred me for the truest of faith that was within me. They crowned me the most famous king of learned justices who ever was enthroned in Troy or was be Ii eved ever should be, to honor my honesty of highest virtue, and they handed the scepter to me because I always rewarded right.”

IX. Whereby He is Incorrupt

The bishop, with anguish in his heart, asked him still, though men honored him so, how it might come to pass that his clothes were so clean: “To rags, I think, they must have rotted and been torn into tatters long ago. Your body may be embalmed; it does not disconcert me that no rot touched it, nor any loathsome worms; but the color of your cloth—I know no manner by man’s science that might allow it to remain and last so long.”

“No, bishop,” said that body, “I was never embalmed, nor has man’s learning kept my cloth unspoiled, but the noble King of Reason who always approves justice and loves wholeheartedly all the laws that pertain to truth; and He honors men more for bearing justice in mind than for all the reward-producing virtues that men on earth acknowledge; and if men have thus arrayed me for justice, He who loves right best has allowed me to last.

X. The Corpse Tells of Its Damnation

“Yes, but tell of your soul,” then said the bishop. “Where is she placed and situated if you so properly performed? He who rewards each man as he has served justice could scarcely ignore to give some branch of His grace. For as he says in his true psalm written: ‘the righteous and the spiritually pure come always to me. ‘ Therefore, tell me of your soul, where she resides in bliss, and of the noble restoration that our Lord handed to her.”

Then he who lay there murmured, moved his head, gave a very great groan, and said to God: “Mighty Maker of men, Your powers are great; how might Your mercy come to me anytime in the future? Was I not an ignorant pagan who never knew Your covenant, the measure of Your mercy, or the greatness of Your virtue, but always a man lacking in the true faith who failed to know the laws in which You, Lord, were praised? Alas, the painful times! I was not of the number for whom You were ransomed, suffering affliction with the blood of Your body upon the sad Cross. When You harrowed the pit of Hell and took Your remnant out from limbo, You left me, and there my soul remains that it may see no farther, languishing in the dark death that was created for us by our father, Adam our ancestor, who ate of the apple that has poisoned many blameless people forever. You all were poisoned along with his teeth and taken into the moral corruption, but with a medicine you are cared for and made to live—that is through baptism in the baptismal fountain and true belief, and both have we all missed without mercy, myself and my soul included [i.e., he lacked both physical baptism as well as the grace it imparts]. What have we who always did right won with our good-deeds, when we are sorrowfully damned into the pit of Hell, and so exiled from that supper, that solemn feast, where those who hungered after righteousness are fully refreshed? My soul may sit there in sorrow and sigh very coldly, dimly in that dark death where morning never dawns, hungry within the pit of Hell and desire meals for a long time before she [the soul] can see either that supper or a man to invite her to it.”

XI. Salvation Procured Through Erkenwald’s Tears

Thus mournfully this dead body described its sorrow, until all wept with woe for the words that they heard, and with grief the bishop turned down his eyes; he had no opportunity to speak, so he quickly sobbed until he took a pause and looked with cleansing tears to the tomb, to the body where it lay. “Our Lord grant,” said that man, “that you would have life by God’s leave, long enough that I might get water, and cast it upon you, fair corpse, and speak these words, ‘I baptize you in the Father’s name and his noble Child’s and of the gracious Holy Ghost, and not a moment longer. Then, even though you dropped down dead, it would endanger me little.” With that word he spoke, the wetness of his eyes and tears streamed down and landed in the tomb, and one fell on the face, and the man sighed. Then he said with a sad sound: “Our Saviour be praised! Now praised be You, exalted God, and Your gracious Mother, and blessed be that blissful hour in which She gave birth to You! And also be you, bishop, the relief of my sorrow and the alleviation of the loathsome mournful places that my soul has lived in! Through the words that you spoke and the water that you shed, the shining stream of your eyes, my baptism is attained. The first drop that fell on me diminished all my grief to nothing; right now my soul is placed at the table to supper. For with the words and the water that cleansed us of pain, softly flashed in the abyss of Hell below a ray of light which immediately caused my spirit to leap with unrestrained reIigious joy into the Upper Room where all the faithful ones eat supper solemnly; and there with honor greatest of all a marshall greeted her [the soul], and with reverence he gave a room to her forever. I therefore praise my high God, and also you, bishop, who have brought us from anguish to bliss, blessed are you!”

XII. The Soul Saved, The Body Turns to Dust

With this his sound ceased, he said no more, but suddenly his sweet face diminished and vanished, and all the color of his body was as black as the soil, as decayed as the musty substance that rises in dust powder. For as soon as the soul was possessed by bliss, the craftwork that covered the bones was corrupted, for the ever-lasting life that shall never cease rejects each vainglorious thing that avails so little. Then was the praising of our Lord upheld with love; much mourning and joy were intermingled. They passed forth in procession, and all the people followed, and all the bells in the city resounded simultaneously.

(1) Tolkien, J. R. R.; Gordon, E. V.; Davis, Norman, eds. (1967). “Introduction”. Sir Gawain and the Green Knight (2 ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. xv.

(2) For the reigns of Sighere and Saebbi, see Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of the English People, and Book III:30 and Book IV:11, respectively.

(3) St. Erkenwald, trans. Christopher Cameron, in “A Translation of the Middle English, ‘St. Erkenwald.'” (Master’s Thesis foSubnmitted for Master of Arts Degree, Emporia University, August 9, 1993), p. 77. Availale online at https://esirc.emporia.edu/bitstream/handle/

123456789/1732/Cameron%201993.pdf?sequence=1

(4) Ibid.

(5) For the text in the original Middle English, see “Saint Erkenwald” from The Complete Works of the Pearl Poet, ed. Casey Finch. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993., available online at https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/159122/saint-erkenwald

(6) Cameron, 78

Phillip Campbell, “Salvation of Righteous Pagans in the Poem St. Erkenwald,” Unam Sanctam Catholicam, Aug. 25, 2024. Available online at https://unamsanctamcatholicam.com/2024/08/salvation-of-righteous-pagans-in-the-poem-ist-erkenwald-i