In the Middle Ages, working on the Lord’s Day was as big a problem as it is today. In a heavily agrarian society, there was always work to be done and people were eager to sneak out on Sundays to catch up on it.

The Church’s pastors preached tirelessly against servile work on the Lord’s Day. They denounced it from the pulpit, and sometimes repeat offenders could be denounced and fined. One interesting method the Church used to discourage Sunday work was artistic, through the use of so-called “Sunday Christ” images.

Exploring the Sunday Christ Images of Christendom

The Sunday Christ was a gigantic image of Jesus painted on the wall of the medieval parish intended to discourage violating the Lord’s Day with servile labor. The image is also known as “St. Sunday” and appears throughout Europe—it is also known as Feiertagschristus (Holy Day Christ) in German, Christ du Dimanche in French, Cristo della domenica in Italian, and Sveta nedelja (St. Sunday) in Slovenian. The Sunday Christ images show Jesus suffering, surrounded by objects used in daily work: spades, hoes, sickles, rakes (peasant tools), and the shears, scissors, and mill-wheels of industry. The blades of these tools are turned towards Christ, their tips dripping with blood; sometimes they are literally showed gouging His flesh. The message is that those who work with these tools on Sunday wound Christ afresh by their Sabbath-breaking.

It was also common to see Sunday Christs surrounded by recreational objects, like musical instruments, playing cards, and dice. These were a reproof to those who would forget the solemn nature of Sundays, spending them in revelry, gambling, and drunkenness.

Other variations might be present as well. For example, in this image from St. James parish in Urtijëi in northern Italy’s Tyrol region, we see images of Sabbath-breakers in league with demons: a man yokes his oxen with the aid of devil, a woman baking bread has a demon on her shoulder, and a man dances a jig with a demon:

At St. Breaca’s church in Breage, Cornwall, England (1), we can see a fantastic example of the tools of labor wounding Jesus. The Breage image is also unique as it shows Christ with a royal crown to demonstrate that, despite His suffering, He is still Lord of the World who will punish sinners for inflicting such indignities upon Him:

In this close up from the bottom half of the image, we can see how the implements of work are directed towards Christ’s bloodied leg, as if to suggest that they are wounding Him:

Off to the side from Christ’s bent right elbow, one can see a playing card showing the five of diamonds. This is a warning against wasting ones time in frivolous actvities and gambling on the Lord’s Day. The five of diamonds in particular was likely chosen for its correspondence to the Five Wounds of Jesus:

Another Sunday Christ image from Hessett in Suffolk shows Christ—albeit badly faded—surrounded by tools whose blades point to Him threateningly. As in the image from Breage, a playing card can be seen on the image, to the left of Christ’s head, this time a six of diamonds:

![Warning to Sabbath Breakers, Hessett [147KB]](https://reeddesign.co.uk/paintedchurch/images/hesset1.jpg)

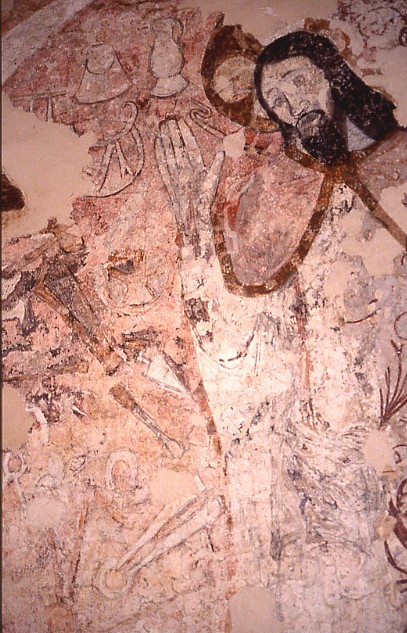

From the Welsh marches comes an excellent example of a Sunday Christ, from Michaelchurch in Eskley, Hereford:

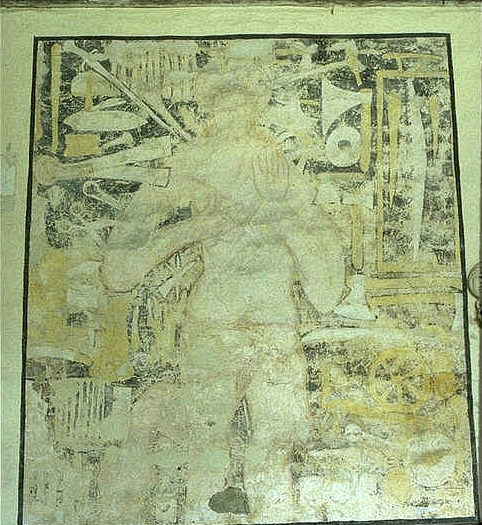

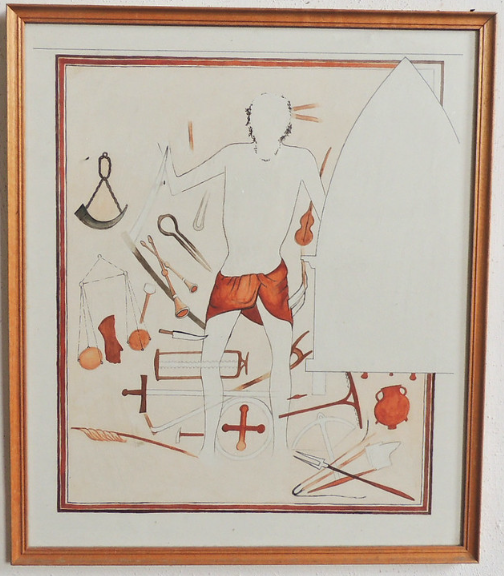

A very old Sunday Christ can be found in St. Cybi’s parish in Holyhead, Wales. The image here is badly faded, and as in other Sunday Christ depictions, it is easier to see the sharp outlines of the tools than Christ Himself:

If you look below the image, you will see a modern rendering of the painting to help visitors identify the different elements in the image:

Below is another example from Oaksey in Bristol. This is an interesting image, as the tools on the right side of the painting were covered with floral designs, evidence of later attempts to retcon the meaning of the Sunday Christ images, which we will discuss below:

To Christ’s right, however, we can still the implements of work, pointed threateningly towards our Lord’s legs:

A particularly splendid example of a Sunday Christ survives in St. Just-in-Penwith, in Cornwall. The St. Just image notable for the clarity of the tools and the preservation and color displayed on Christ’s body. As at Breage, Christ is pointing to His wounds, as if to say, “You are doing this to me when you work on Sunday.”

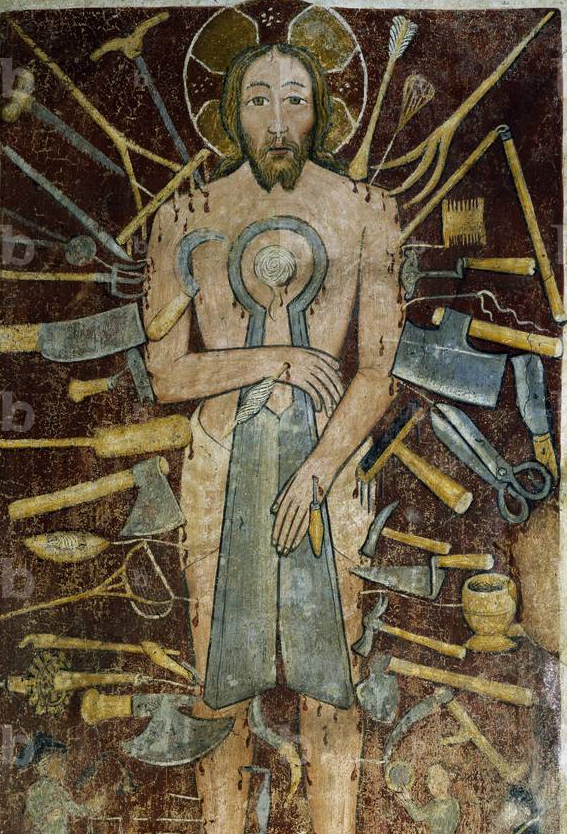

While England and Wales furnish many examples, Sunday Christs can be found in other regions as well. We have already seen the beautiful example from Urtijei in the Tyrol, but another excellent Italian depiction of Sunday Christ can be found in St. Stephen’s Cathedral in Biella, north of Turin. This fresco has been beautifully preserved:

The Biella image is interesting becayse if you look at Christ’s feet, it show peasants literally attacking Him with their tools, making crystal clear the intended symbolism of the work tools—Sabbath-breakers wound Christ by their Sunday labor.

Another fine Italian example is the Sunday Christ of San Pietro de Feletto in Treviso, a parish church filled with rich wall decorations dating back to the 12th century:

One of the best preserved examples from the German-speaking countries comes from the parish church of Saak, in Nötsch im Gailtal in Carinthian Austria. This is, in my opinion, perhaps the most spectacular of all surviving Sunday Christ images for its color, contrast, detail, and the unique presence of the actual cross, which is not seen in most other Sunday Christ images:

One final example that is particularly colorful is the Sveta nedelja (“St. Sunday”) from the Church of the Annunciation in Crngrob, Slovenia. This image was painted by the renowned Slovenian artist Johannes de Laybaco (Janez Ljubljanski) In this image, we see the usual Christ surrounded by the implements of trade, but the St. Sunday image is set within a larger framework of horizontal panels depicting images of Sabbath-breaking: harvesting grain, combing wool, and engaging in various recreational activities. At the bottom, these Sabbath-breakers are all marching off into the mouth of a beast at bottom right, signifying their damnation for breaking the Third Commandment:

Here is a modern reconstruction of the painting, bringing out the color and lines in greater detail:

Transformation into “Christ of the Trades”

Most Sunday Christ images appeared sometime after 1350, reached the height of popularity during the 15th century, and went into decline during and after the Reformation. Why the images appeared after 1350 is a matter of conjecture; some historians point to the Black Death as a catalyst. Western Christendom saw a rise in Holy Days of Obligation after the Black Death. Given the drop in European population in the decades after the plague, the increase of Holy Days would have fallen harder on the peasantry, who had less work days upon which to do more work. This would have constituted a greater temptation to working on Sundays and Holy Days, perhaps prompting a response by pastors in the form of the Sunday Christ images.

Whatever the origin of these images, the popualr mood seems to have changed by the mid-16th century. Not only do we see a decline in the production of Sunday Christs, but in some cases, there were deliberate attempts to efface or retcon the images. Recall how the Oaksey image from Bristol was partially obscured by a later artist who covered the right side of the image with a floral design to efface the depictions of the threatening tools. In other images—especially in England—Christ Himself seems to have been erased. At St. John’s in Duxford, Cambridgeshire, the image of Christ has been erased, the only evidence of His presence being the surviving outlines of the farm implements that once surrounded Him:

In this particular case, the effacement was likely related to the iconoclasm of the Puritan era, as Cambridge was a stronghold of Puritanism during the early 17th century.

We would expect the Sunday Christ images to be subject to such effacement in areas strongly affected by the Reformation, but even predominantly Catholic areas, the Sunday Christ images were generally retconned with a reinterpretation—no longer a warning against Sabbath-breaking, the Sunday Christ images were interpreted as Christ sanctifying or blessing the tools of labor, a motif known as “Christ of the Trades.” This was also a common theme in Anglican parishes whose medieval Sunday Christ images survived the Reformation. Confused and embarassed by the bloody penitentialism of the medieval paintings, Anglican clergy of the Georgian and Victorian era explained the images as signs of Christ’s blessing upon manual labor. This is obviously a retcon, as there is nothing in any of the images to suggest such a meaning. Christ’s battered visage, literally being ripped and gouged by bladed tools dripping in blood, clearly demonstrate an antagonism between Christ and the tools of labor. Furthermore, no Sunday Christ image shows Jesus in any posture of blessing; in paintings where He does have a determinant posture, He is pointing to His wounds. Retired senior lecturer Anne Marshall of Buckinhamshire’s Open University has an excellent website analyzing the Sunday Christ images of the U.K., demonstrating that the “Christ of the Trades” interpretation is untenable.

But why was the image reinterpreted? Drawing inspiration from the horrors of the Black Death, the art of late fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries was notoriously macabre and penitential in mood. This was the age of the Flagellants and the Danse Macabre, when piety was characterized by a dark and sometimes gory exploration of physical mortality. It was an interesting moment in the history of Catholic piety, but very bound up with the ideas and anxieties of that particular age. By the post-Tridentine era, pious sensibilites had evolved considerably; the looming images of a bleeding Christ being tortured by shears and rakes as a warning to sinners may have seemed inappropriate decorum for the high culture of the Baroque, leading to the images being erased, altered, or at the very least, reinterpreted. This, too, is only a theory, but not an implausible one.

Whatever the reason for their creation and eventual reinterpretation, Sunday Christ images are a testimony to the medieval Church’s attempts to combat Sabbath-breaking by reminding the faithful of the importance of the Sunday rest.

(1) For more on the Christ of Breage, see this excellent article: https://reeddesign.co.uk/

paintedchurch/breage-sabbath-breakers.htm

Phillip Campbell “Sunday Christ Images,” Unam Sanctam Catholicam, Sept. 1, 2024. Available online at https://unamsanctamcatholicam.com/2024/09/sunday-christ-images