In order to get a proper understanding of the events at Medjugorje, it is necessary to go beyond the issue of the seers and the apparitions themselves and look at the larger context of what has been going on in Herzegovina for decades relative to the situation of the local Franciscan Friars and the diocesan clergy. For years the a small but influential segment of the Herzegovinian Franciscans has been in conflict with the See of Mostar-Duvno over the administration of some parishes that the Holy See commanded be transferred from the Franciscans to the diocese in 1975, but almost fifty years later still has not happened. This conflict is referred to as the “Herzegovina Question” or the “Herzegovnia Affair” and is central to understanding the alleged apparitions at Medjugorje. In fact, as we shall see, the evidence seems to suggest that the Medjugorje phenomenon was leveraged as a means of helping a handful of dissident Franciscans avoid resolving the Herzegovina Question.

The History of Catholicism in Herzegovina

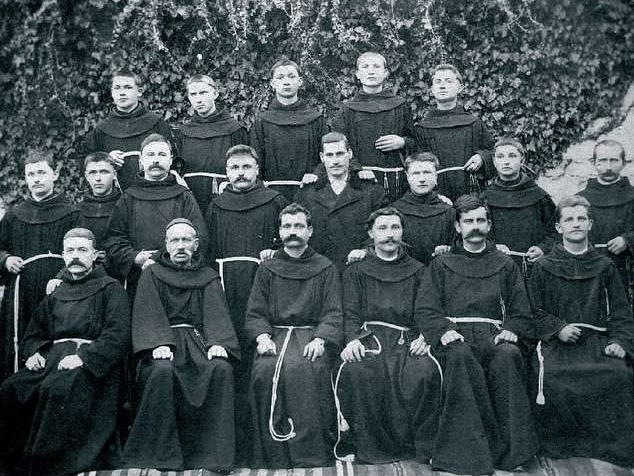

The roots of the conflict go back centuries, to the time of the Ottoman domination of eastern Europe. The Franciscans came to Bosnia-Herzegovina as missionaries in the 14th century, when the area was still a Latin Christian kingdom. The region was conquered by the Ottomans in 1463, although the Franciscans were permitted to remain due to the intercession of Angelus Zojezdovic, who personally plead with Sultan Mehmet II to grant Christians free exercise of their religion. This was granted and confirmed in a special oath given by Mehmed II in May of 1463. The Franciscans were allowed to remain to minister to the Latin Christian Croats. The Catholic bishops, however, were run out of the province.

Without an episcopate, the diocesan clergy soon withered away and the Franciscans became the only pillar of Christianity in Bosnia-Herzegovina. This situation endured for four and a half centuries, during which time the Franciscans heroically guided the Croats in preserving the Catholic Faith.

The Holy See did not simply give up on the region, however. To support the local church as it attempted to function without resident bishops, the Holy See founded an Apostolic Vicariate for Bosnia in 1735, and assigned Franciscans as apostolic vicars to direct it. The Franciscan Province of Bosna Srebrena was restructured to correspond to the borders of Ottoman rule in 1757; it split in 1846, when friars from the Kresevo monastery broke off to found the monastery at Siroki Brijeg. Pope Leo XIII established the Franciscan Province of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary in 1892.

But by then the situation had drastically changed. The crumbling Ottoman Empire, retreating against the incursions of the land hungry European powers, withdrew from Bosnia in 1878 and the ancient homeland of the Catholic Croats came under the administration of the Austria-Hungarian Empire. With the restoration of these lands to Catholic rule, the pope was able to restore the hierarchy, and in 1881 the episcopacy was restored and bishops were appointed.

With the reestablishment of the hierarchy came the necessity of transferring the administrative control of Herzegovina’s parishes from Franciscan back to diocesan control, since it is highly irregular for a religious order to have administrative authority over the parishes of a diocese, as the bishop is the rightful pastor of a diocese, not a religious order.

Franciscans Refuse to Hand Over the Parishes

The Franciscans were understandably reluctant to facilitate this transfer. They had heroically defended and preserved Catholicism in the region for four centuries in the face of Turkish oppression. Over the centuries they had begun to think of the parishes as their own and of themselves as the rightful pastors of the Herzegovinian people. Yet this transfer was necessary and is an ordinary part of the process of settling diocesan clergy into parishes once a given area begins to emerge from missionary status. World War I and World War II interrupted this transfer of property, but in the 1940’s the bishops of the three dioceses of Herzegovina began to get more adamant in their insistence that the parishes be handed over to diocesan clergy, and while many Franciscans complied with the bishops’ wishes, many did not.

By the end of the 1940’s, the two Franciscan provinces still held 63 of 79 parishes in the dioceses of Vrhbosna and Mostar. (1) The tumultuous years of the Second Vatican Council brought more chaos, and in the early 1970’s the friars of Herzegovina became more aggressive in their resistance to the bishops, forming alliances and organizations that openly flouted the bishops’ authority and resisted the diocesan take-overs. Many lay people joined these organizations of dissent as well, despite the Vatican’s support for the bishops’ side in the controversy.

Romanis Pontificibus

The conflict became so severe that Pope Paul VI had to intervene personally. In June, 1975 he issued the document Romanis Pontificibus which ordered the return of the parishes to the diocesan clergy. Romanis Pontificibus is an extraordinary document which, given the circumstances, is extremely generous to the Franciscans. Despite the fact that all parishes were to be returned to the diocese, the decree of Paul VI allowed the Franciscans to retain over a third of the parishes, a situation that probably does not exist in any other part of the world. The decree would allow 30 parishes to the Franciscans and leave 52 to the diocesan clergy.

Romanis Pontificibus quotes the Vatican II document Christus Dominus on the authority of bishops, saying, “‘All Religious should always look upon the bishops, as upon successors of the Apostles, with devoted respect and reverence. Whenever [religious] are legitimately called upon to undertake works of the apostolate, they are obliged to discharge their duties as active and obedient helpers of the bishops’. This norm, as is obvious, indeed applies even more to those religious to whom the care of parishes is entrusted.” (2)

After laying down a general catechesis on the authority of bishops and the duty of religious in any diocese to render obedience and respect to bishops, especially in cases where the Holy See has intervened, Paul VI goes on to propose a division of parishes, allowing some to remain under the jurisdiction of the friars:

“1. Attentive to the mutual agreement between the two parties with an interest here, and in consideration of the merits which the Friars Minor of the Province of Herzegovina have secured for themselves, the Holy See accepts that it be taken as a general rule that half of the faithful of the diocese of Mostar-Duvno remain entrusted to the pastoral care of the same religious, while the other half entrusted to diocesan clergy. This apportionment – once there will be an equal number of the faithful entrusted to each party, according to this generally set-out plan – will remain legitimate in the future.” (3)

The Holy Father then takes the unusual step of calling out specific parishes by name and commands them to be handed over to the Bishop of Mostar-Duvno:

“4. The Franciscan Fathers, within one year from the day of the promulgation of this decree, must hand over to the diocesan clergy the parishes of Blagaj, Jablanica, Ploče, and Nevesinje.

But, according to this same decision of the [Sacred] Congregation, the entire pastoral care of the parish of Čapljina, with no part of its territory being taken away, must be transferred within a year from the Franciscan Fathers to the diocesan clergy. The Ordinary of Mostar-Duvno will reimburse the Province of the Friars Minor of Herzegovina the costs undertaken by the Franciscan Fathers for the building of their religious residence, but not the costs for constructing the church of the parish.

7. Likewise from the parish of Humac, which up to now has been wholly entrusted to the pastoral care of the Friars Minor, territory will be separated in which, in the meantime, there will be erected, within one year, according to the agreement of the two parties concerning this, parishes Crveni Grm-Prolog and Zvirić-Bijača, to be entrusted to the diocesan clergy.” (4)

The Franciscans were still dragging their feet, however, and by 1980 they still retained 10 parishes illegally. (5) The Holy See would eventually impose penalties on the Herzegovinian Franciscans for their disobedience, depriving them of the right of electing a superior and instead granting them one by appointment. A few parishes would be handed over, but by 1990, the Franciscans still retained seven illegally, fifteen years after Paul VI ordered their transfer.

Medjugorje

At this point we have to stop at note the chronology here. In 1975, Paul VI issues Romanis Pontificibus commanding the return of the parishes they hold illegally. In 1980, the Holy See begins proceedings to discipline the Herzegovinian Franciscans. The following year, 1981, the six “seers” of Medjugorje have their first alleged apparitions. Their “spiritual director” and chief promoter, Fr. Jozo Zovko—whom the Gospa of Medjugorje called a saint (6)—appears on the diocese of Mostar’s official website on a list of Franciscans who refused to sign a declaration of obedience to the bishop and who were subsequently expelled from the Franciscans. (7) Fr. Jozo has been suspended since 1989 for his refusal to obey the legitimate Bishop of Mostar Duvno. (8)

The chronology suggests a clear connection between the Medjugorje apparitions and the Herzegovina Question via the pastor of Medjugorje and the seers’ spiritual director, Fr. Jozo Zovko. The promotion of the Medjugorje apparitions by the Franciscans is not coincidental, nor is the timing of the alleged apparitions, both occurring in 1981, right as the Holy See was beginning to intensify pressure on the Franciscans for the return of the parishes to the bishop. The implication is clear: the Franciscans of Herzegovina (or at least some of them) conspired with the seers, mere children at the time, to create a fabricated apparition at Medjugorje for the purpose of drawing international attention to the site, and to the Franciscans who were still illegally retaining control of ten parishes. After Medjugorje had attained celebrity status, any attempt by the bishop to exert his proper rights in obtaining control of the parishes would look like an effort to oppose the Virgin Mary herself. Once Medjugorje obtained this recognition, this did in fact happen: the phenomenon there took on a life and direction of their own, and to this day millions of Catholics flock to Medjugorje despite the prohibition by the bishop of public or private pilgrimages.

The Case of Fr. Barbaric and Fr. Rados

One of the parishes explicitly mentioned in Romanis Pontificibus, that of Capljina, affords us an excellent example of the ongoing disobedience of a small segment of Franciscans in Herzegovina.

Pilgrimages to Medjurgorje declined tremendously in the early 1990’s due to the Balkan War, giving the bishops greater opportunity to exert pressure on the Franciscans once the hostilities ceased. The then Procurator General of the Franciscan Order, Antonio Riccio, OFM, struck an agreement with Msgr. Ratko Peric, Bishop of Mostar, that one of the disputed parishes in the town of Capljina would be handed over to the diocesan clergy. However, when the appointed day came for the transfer of property to the diocesan clergy, the Franciscans in charge of the parish, Fr. Boniface Barbaric and Fr. Bozo Rados, refused to comply. This prompted their expulsion from the Franciscan Order:

“Antonit Riccio, OFM Procurator General to Msgr. Ratko Peric:

The General Minister, Brother Hermann Schaluck, and the Bishop of Mostar and Duvno, Msgr Peric, had decided that, in order to bring into effect the Decree Romanis Pontificibus, the parish of Capljina, formerly entrusted to the Province of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary, would from 12th May 1996 be handed over for the Bishop to dispose of at his unfettered discretion. Accordingly, no Franciscan was authorized to reside within that parish and carry out pastoral duties within it. This was made known to all Franciscans in the Province.

Brother Boniface P. Barbaric and Brother Bozo Rados declined to be transferred, and remained in Capljina, despite repeated and authoritative requests and orders to the contrary.

Since they have persisted in disobedience, the procedure for their expulsion from the Order was set in train. On 28th February 1998 a general consistory of the Order voted unanimously in secret ballot to expel Brother Boniface P. Barbaric and Brother Bozo Rados of the Province of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary in Bosnia and Herzegovina from the Order of Friars Minor, in accordance with the provisions of section 1 of Canon 699.” (9)

Following their explusion, the Bishop of Mostar in conjunction with the Provincial Superior of the OFM issued a joint statement to all of the priests and faithful of Mostar-Duvno that Romanis Pontificibus would be fully implemented and that the disobedience of certain Franciscans would not be tolerated. The statement, from December of 1998, states that:

“Disobedient Franciscans should know that they are liable to be punished according to Canon Law and the rules of their Order. It is desired that the Decree should at long last be implemented for the good of the Church, the diocese, the Franciscan province, and, above all, the faithful. We remind Christian believers that sacraments which they receive from the condemned Franciscans are invalid. It is important that all, both clerics and the faithful, should see the local bishop, who is working with the secular and religious clergy, as the centre and object of diocesan ecclesiastical life.” (10)

Attempts at Resolution

The Medjugorje phenomenon has stalled the resolution of the Herzegovina Question, which is precisely what the disobedient Franciscan architects of the scheme wanted. At this time [ed. this article was written in 2012], the Bishop of Mostar Duvno still states that Romanis Pontificibus has not been fully implemented. Diocesan clergy have been met with the physical occupation of churches, threats, and even some violence by occupiers. The superiors of the Franciscan Order from Rome ordered compliance with Romanis Pontificibus in 1999, and the local Franciscans expressed willingness to comply. Much work was done leading up to this decree in 1999, but even after the 2001 General Chapter of the Franciscan Province stated that Romanis Pontificibus had been implemented, Bishop Peric reported that it had not. Seven parishes were still being held illicitly by rebellious Franciscans.

This situation prompted Pope John Paul II himself to intervene in 2003, when once again asked the members of the General Chapter of the Franciscan Order to carry into effect the decision of his predecessor, Pope Paul VI, going back to 1975:

“Your missionary activity will prove fruitful in so far as it is fulfilled in harmony with the lawful pastors to whom Our Lord has entrusted responsibility for his flock. Bearing that well in mind, I once again warmly remind you of the efforts that have been made to overcome the difficulties that have long existed in certain areas. It is my heartfelt wish that, with co-operation on every side, that understanding with the diocesan authorities sought by my worthy predecessor, Pope Paul VI, should be fully attained. It has become apparent that such an understanding is a prerequisite for effective evangelisation.” (11)

The pope’s words are characteristically mild. Bishop Peric put the matter more succinctly in a statement four years later in 2007. Thirty-two years after Romanis Pontificibus, the Franciscans were still illegally occupying five parishes and administering invalid sacraments. Bishop Peric stated:

“In the diocese of Mostar-Duvno there exists a problem which in recent years has practically become a schism. At least nine Franciscan priests, who have been expelled from the Franciscan OFM Order and suspended a divinis, have rebelled against the decision of the Holy See and have not allowed the transfer of some of the parishes from Franciscan to Diocesan administration. They forcefully occupy at least five parishes, all the while continuing with all priestly functions. They invalidly perform marriages, hear confessions without canonical faculties, some of them invalidly confirm youngsters, and in 2001 they invited an old-Catholic deacon who falsely presented himself as a bishop to “confirm” about eight hundred young people in three parishes. Two of these expelled Franciscans even went as far as asking the Swiss old-Catholic bishop, Hans Gerny, to ordain them as bishops, yet they did not succeed. So many invalid sacraments, so much disobedience, violence, sacrilege, disorder and irregularities and not even a single “message” amongst the tens of thousands of “apparitions” has been sent to alleviate these scandals. A very strange thing indeed!” (12)

And why has Bishop Peric been unable to put an end to this disobedience despite the support of the Holy See and of the Superior General of the Franciscan Order? There is one reason and one reason only: Medjugorje. Without the global support of their Medjugorje adherents, who funnel millions upon millions of dollars to the dissident parishes, there is no way the Franciscans could endure in a state of disobedience and schism so long, financially or morally. If Medjugorje were not a factor—if this were an issue of a handful of isolated, obstinate Franciscans—the Herzegovinian Question would long ago have been solved. It is the farce of Medjugorje, created by the dissident Franciscans, which keeps the Herzegovinian Question open, prevents the bishop from exercising his authority, and allows a handful of Franciscans a monopoly over an astonishing amount of influence, both spiritual and financial. The Medjugorje apparitions serve as a cash-cow that allow the seers and the disobedient Franciscans to maintain control over a lucrative private empire.

Violence and Mass Murder in Medjugorje

Like any other private empire where obscene amounts of money are at stake, the disobedience of the Franciscans that supports the multi-million dollar Medjugorje kingdom has led to violence and even murder between different family clans as they struggle with each other over control of the lucrative market in Medjugorje religious trinkets.

This was documented in Dutch sociologist Mart Bax’s study of Medjugorje. Bax spent fifteen years studying the events and people of the village from a sociological perspective and was able to document the dark underside of life in Medjugorje that most adherents of the Queen of Peace never hear about. (13)

The Queen of Peace brought millions of tourists who pumped huge sums of money into the local economy. But as the state monopoly on power evaporated in 1991, Croat nationalism reasserted itself, often under the leadership of the Franciscans. In Medjugorje, the Serbs were quickly driven out by 1991 but the ensuing civil war began to cut into the tourist trade and competition became fierce. Tour groups were often waylaid or prevented from reaching their destination. Villagers often took out loans to expand their homes in order to house pilgrims. Clans kept their rivalries in check as long as the money flowed in from tourists. But by 1991 most of the boarding houses were empty except for those owned by the Ostojici clan, who had good outside connections. Other clans asked the Ostojici to share their good fortune; the Ostojici declined.

What can only be described as a blood feud was soon ignited in Medjugorje and the surrounding towns that killed two hundred members of the village of three thousand and caused another six hundred to flee the region. Pilgrims at the Medjugorje Peace Center did not even realize the feud was ongoing although grisly atrocities—including mutilations and torture—were carried out on a regular basis between the warring clans in nighttime raids. Villagers aligned to one or the other of the clans mutilated and tortured each other, elderly people were murdered, homes were burned, and women and children killed. Bax noted that violence became more organized even as it became more grisly. In regards to mutilation, he reported the clans followed a fixed pattern with more and more parts of bodies being removed as the conflict increased. Finally, units of the Croatian Army aligned with another one of the warring clans intervened against the Ostojici; a hundred men were rounded up and summarily executed in one of the many ravines in the area. Homemade rocket launchers were used to chase out the Ostojici who remained.

By the end of 1992, Medjugorje was again accessible to tourists. Houses were being built and repaired. Visitors who noticed the damage done by the violence were lied to and told that Serb aggressors had done the damage to the village. The Ostojici property was taken over by their rivals, the remaining Ostojici having fled as refugees to Germany.

As for the Queen of Peace, Bax reports the victors from both clans offered up prayers of thanks for her special grace and protection during the massacres. These facts are also documented in Michael Davies’ book Medjugorje After Twenty-One Years. (14)

Fruits of Disobedience

This study is not meant to call into question the faithfulness of the majority of Franciscans in the three dioceses of Herzegovina. Indeed, the Franciscans to this day retain a very special place in the culture of Bosnia and even constitute a majority of the priests in the region. As of 2010, there were 358 religious order priests to 263 diocesan priests in the three dioceses that make up the ecclesiastical province of Herzegovina. (15) The Franciscans still have an important role to play in the life of the Herzegovinian church, something the Holy Father and the bishops of Mostar Duvno have always acknowledged.

Still, it is sad that the disobedience of a few has tarnished the good name of an order that has done so much good in the Balkans throughout the centuries. In refusing to return the contested parishes to the rightful jurisdiction of the diocesan clergy and in conspiring to promote and defend the spurious apparitions of Medjugorje as a means of avoiding the dictates of the papacy as laid down in Romanis Pontificibus, this small cadre of disobedient Franciscans have not only brought shame upon themselves, but have led millions into error, using the Medjugorje phenomenon to promote their own agenda and taking countless number of souls along with them into their dissent. As pilgrimages are technically forbidden to Medjugorje by the Bishop pf Mostar Duvno, every single person who makes a pilgrimage there is guilty of a formal act of disobedience. Their individual culpability is another question, but it is still a grave matter.

Even graver is the people who, by being caught up in the money-making scheme that Medjugorje has become, have been led to commit terrible acts of violence in order to corner the “Medjugorje Market.” All sin has consequences, and in the chaos, error and violence we have document we finally see the real fruits of Medjugorje. May the faithful who are taken in by this deception wake up from their slumber, and may the handful of disobedient Franciscans submit to the Bishop of Mostar and the decrees of the pope in Romanis Pontificibus so that the Herzegovinian Question may be settled once and for all.

1. Vjekoslav Perica (2004). Balkan Idols: Religion and Nationalism in Yugoslav States. Oxford University Press. pp. 117–118.

2. Christus Dominus, 35:1

3. http://medjugorjedocuments.blogspot.com/2010/11/1975-decree-romanis-pontificibus.html

4. ibid.

5. Perika, 117-118

6. René Laurentin, Corpus Chronologique des Messages, O.E.I.L., Paris, 1987, p.159

7. http://cbismo.com/index.php?menuID=36

8. http://www.marcocorvaglia.com/medjugorje-en/father-jozo-a-disobedient-franciscan.html. In the text of Fr. Zovko’s suspension, the Bishop of Mostar, Ratko Peric, states the reasons for the suspension being “to defend this local Church from your abuse, whilst not entering into the religious discipline of your congregation, and having in mind your constant disobedience in this local Church and your lack of respect towards the decisions of the Diocesan Bishops.”

9. http://www.unitypublishing.com/Apparitions/MedjugorjeFranciscans.html

10. ibid.

11. http://www.cbismo.com/index.php?mod=vijest&vijest=287

12. http://www.cbismo.com/index.php?mod=vijest&vijest=101

13. The following facts all come from Mart Bax’s 1995 book documenting his fifteen years in Medjugorje, Medjugorje: religion, Politics, and Violence in Rural Bosnia. Free University press, Amsterdam, 1995, pgs. 122-3. See also: http://fantompowa.net/Flame/

levy_medjugorje.htm

14. Michael Davies. Medjugorje After Twenty-One Years. Remnant Press; 2nd edition, 2002, p. 66

15. http://medjugorjedocuments.blogspot.com/2010/11/1975-decree-romanis-pontificibus.html

Phillip Campbell, “Medjugorje: Understanding the Herzegovina Questions,” Dec. 6, 2012, Unam Sanctam Catholicam. Available online at https://unamsanctamcatholicam.com/2024/09/medjugorje-understanding-the-herzegovina-question