:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/frederick-barbarossa-large-57c4b9bc5f9b5855e5f68334.jpg)

Mid-twelfth century Italy was a time of intense political struggle in which the peninsula was torn by five rival powers, including the Normans, Byzantines, the Papal States, Lombard League, and the Holy Roman Empire. The papacy was in a particularly tough spot, as popes Adrian IV (1154-1159) and Alexander III (1159-1181) struggled against the tenacious efforts of the Normans in the south and Hohenstaufens in the north to subjugate all of Italy.

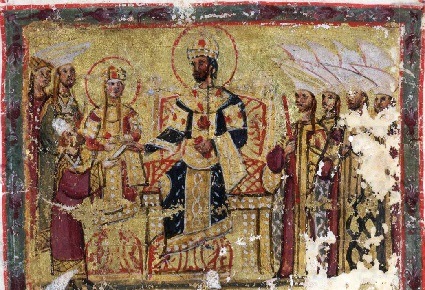

Manuel Komnenos, Emperor of Constantinople (r. 1143-1180) had been eagerly monitoring the situation through his emissaries in the Italian peninsula, ever hoping to exploit the problems of Italy for the benefit of Byzantium. Manuel had much to gain from an alliance with the pope. During the mid-12th century, Byzantium was holding pockets of territory along the southern Italian coast, notably in the regions of Apulia and Calabria. These territories were under intense pressure from the Sicilian Normans, however, who were aggressively expanding their kingdom in southern Italy.

Manuel Floats Reunion to Adrian IV

The 1150s saw the Byzantines and Normans warring openly in southern Italy for hegemony, but the Normans also made themselves a nuisance to the papacy, coveting the Papal States. Manuel suspected that the papacy would rather have Byzantium for a southern neighbor than the unruly Normans and had begun floating the idea of reunion of churches in exchange for papal support for Byzantium’s claims. Feelers for reunion were put out as early as 1155 under the pontificate of Adrian IV. Manuel offered a large sum of money to Adrian for the provisioning of troops, with the request that Adrian grant him emperor lordship of three maritime cities in return for assistance in expelling the Normans and their rowdy King William from Sicily. Manuel sweetened the offer by promising to pay 5,000 pounds of gold to the papacy. [1]Adrian was amendable, and an alliance was formed between Manuel and Pope Adrian, in which union of the Churches was to be established at the price of Byzantine hegemony in southern ItalyUnfortunately for Manuel, his military situation rapidly deteriorated. Manuel’s forces were soundly defeated at the Battle of Brindisi (1156) forcing Manuel to exit the war and cede Apulia and Calabria to William of Sicily. The Byzantine forces evacuated Italy in 1158, never to return. Pope Adrian was compelled to make peace with the Normans by the Treaty of Benevento, which locked the Papal States into an alliance with Norman Sicily, much to the annoyance of the powerful Frederick Barbarossa, Holy Roman Emperor (r. 1155-1190).

Manuel did not give up his hopes of a restored Byzantine Empire in souther Italy, however. Two years after Brindisi, a new pope was on the throne—Alexander III—and a schism bad broken out with Barbarossa. Barbarossa opposed the new pro-Norman orientation of the Holy See and supported the anti-pope Victor IV against the claims of Alexander. Backed by the might of Barbarossa, Victor proved a formidable threat, even driving Alexander III from Rome in 1162. Emperor Manuel saw the pope’s difficulty as his opportunity and began sending out feelers to Alexander III about reunion, to which the pope was amenable.

Manuel Offers Union and Submission to Alexander III

A formal offer of reunion of the churches came in the year 1167, when Emperor Manuel sent an embassy of his most distinguished secretaries with a great sum of money to the papal court in exile at Benevento. The emissaries conveyed the following message to Pope Alexander, which has been preserved in Alexander’s vita by his biographer Boso. According to Boso, the message read as follows:

Our lord the emperor [Manuel Komnenos] has long had a very great desire to honor and increase the esteem for his mother, the Roman Church. But when he now sees Frederick, that Church’s champion, whose duty it is to protect it from others and defend it, become [instead] her attacker and persecutor, his desire to serve and succor her is even stronger. And that in these days the phrase of the Gospel, “and there will be one fold and one shepherd” may be fulfilled, he wishes to unite and subject his Greek Church to the Church of Rome, in that status in which we know it to have been of old, if only you are willing to restore his rights to him. For this reason he asks and begs that when the enemy of the Church has been deprived of the crown of the Roman Empire, you restore it to him [i.e., to Manuel], as reason and justice requires. To bring this about, he is ready to bestow and expend immediately whatever you in your good pleasure consider necessary in sums of money, soldiers, and armaments. (2)

This proposal was incredibly ambitious in what it affirmed, what is asked, and what it pledged. First, what it affirmed:

(1) The text affirms that the Greek Churches were historically subject to the See of Rome “in that status in which we know it to have been of old.”

(2) It admits that the imperial title had been transferred from the Greeks to the West by the pope according to the legal doctrine commonly known as translatio imperii. Manuel affirms this doctrine, for, in asking the pope to voluntarily give the imperial title back to Constantinople, he is thereby admitting that the pope both had removed it in the past and had the power to restore it again unto him.

Second, what it asks:

(1) Manuel asks Pope Alexander to declare Emperor Frederick Barbarossa deposed and to bestow the Frederick’s crown upon himself, thus uniting the domains of Barbarossa and Manuel. Manuel must have known that ascending to the lordship of Germany was a practical impossibility; what he likely hoped for was to detach Barbarossa’s Italian domains from the Holy Roman Empire and preside over a restored Byzantine hegemony in Italy with a title legitimized by the pope. As mentioned above, this request implies acknowledgement that the pope has the power to legitimize (or delegitimize) the imperial title.

Finally, what is pledges:

(1) Manuel pledges the submission of the Greek Church to the Church of Rome.

(2) He also pledges to offer material support to the papacy to defeat the forces of Barbarossa and the schismatic anti-pope, in money, soldiers, and arms. In essence, Manuel seeks to fund Alexander’s struggle against Barbarossa. He is willing to sacrifice the autonomy of the Greek Church to this cause if it will net him the acquisition of Italy under a title recognized and legitimized by the pope.

Alexander’s Response

Like his predecessor Adrian IV, Pope Alexander III was eager for reunification of East and West, but could see that Manuel’s proposal had the potential to exacerbate a conflict he was trying hard to defuse. The pope took counsel with his Cardinals, who shared his misgivings. In the end, Alexander rejected Manuel’s offer and sent him the following response, also preseved by Boso:

We give thanks to your lord the emperor as to a most Christian prince and a most devoted son of St. Peter, for his devout and persevering embassies, and for the display of the good will which he bears towards the Holy Roman Church. On these accounts we listen with pleasure to his most affectionate words. In so far as we can, in obedience to God, we wish with fatherly kindness to fulfill his requests. But what he asks goes very deep and is exceedingly complicated, and since the decrees of the holy fathers forbid such requests on account of their inherent difficulties, we neither can nor ought to grant our assent under terms of this sort, since by reason of the office entrusted to us by God it is fitting that we be the authors and guardians of peace. (3)

Pope Alexander rejects the proposal of Manuel on two grounds (1) that is is “exceedingly complicated”, and (2) that “the holy fathers forbid such requests on account of their inherent difficulties.”

It is unfortunate that Alexander did not elaborate his points, which leaves us to speculate. His first point likely referred simply to the infeasibility of the plan: the Greek bishops would have to ratify any union, which would they would be unlikely to support and the details of which would undoubtedly take years to hammer out. Military success against Barbarossa was questionable, even assuming Manuel held up his end of the bargain entirely. And the legal quagmire that would arise from establishing Byzantine hegemony in Europe probably gave Alexander a headache. In short, the plan had too many moving parts to be considered a reasonable course of action. We may further surmise that Alexander was not keen on exchanging subservience to one imperial family for another. It was better, if possible, to prevail over a humbled and weakened Barbarossa than to exalt Manuel.

Alexander’s second objection is more curious—that “the decrees of the holy fathers forbid such requests on account of their inherent difficulties.” What decrees of the holy fathers is he referring to? The only clue is the following explanatory clause, which says, “since by reason of the office entrusted to us by God it is fitting that we be the authors and guardians of peace.” Given his reference to guarding peace, we may therefore presume that Pope Alexander was concerned that acceptance of Emperor Manuel’s offer would lead to further wars and disorders whose magnitude would not be justified. Alexander is probably thus thinking of the principle, “one may not do evil so that good may come of it” (cf. Rom. 3:8), which was also affirmed in Gratian’s Decretals. (4) Declaring Barbarossa deposed and transfering the empire to Manuel would certainly not be acknowledged in Germany; such a provocation would clearly lead to fierce reprisals against the papacy from Barbarossa and no doubt prolong war in Italy—and, at the end of the day, the prospect of success was far from certain. Alexander likely concluded Manuel’s plan would unleash such disorders across the Christian world that it could not be justified on moral grounds, even for the sake of reuniting East and West.

Conclusion: The Battle of Legnano and Aftermath

Having rejected Manuel’s offer, Pope Alexander returned the amabassadors’ gifts and sent them back to Manuel, hoping to prevail over Barbarossa by other means. We know that Manuel did not give up right away; another offer of union followed in 1169, which was rejected on similar grounds. (5)

Manuel was not ready to abandon his ambitions in Italy, however. Instead of allying with the papacy, he began funding the Lombard League, a federation of northern Italian cities hostile to Barbarossa. His money was instrumental in maintaining their opposition; when Barbarossa destroyed the walls of Milan, for example, they were quickly rebuilt with gold from Manuel’s coffers. In 1176 the Lombard League won a decisive victory over Frederick Barbarossa at the Battle of Legnano. Manuel’s position improved substantially. Though he fell far short of any kind of restored Italian hegemony, several Italian cities on the Ligurian coast pledged fealty to Manuel, including Cremona and Pavia.

If there ever was a real chance of successful reunion of East and West during the Middel Ages, it was likely during reign of Manuel Komnenos, when the emperor eager to exchange the haughty independence of Constantinople for a stake in Italy. With the outrages of the Fourth Crusade still in the future and the schism scarcely more than a century old, the bonds of unity between Greek and Latin were not so far distant as to be beyond repair, and the common enemy of Norman and Hohenstaufen gave the papacy incentive to look outside Italy for material support. Though circumstance ultimately did not favor the plans of Manuel, his proposal of submission remains one of great “what ifs” of Church history.

(1) J. Duggan, The Pope and the Princes: Adrian IV, the English Pope, 1154–1159 (Ashgate Publishing: Farham, U.K., 2003), 122

(2) Boso, Life of Alexander III, trans. G.M. Ellis (Basil Blackwell: Oxford, 1973), 76-77

(3) Ibid., 77

(4) For example, in the chapter “Ne quis” (causa xxii, q.2)

(5) J. W. Birkenmeier, The Development of the Komnenian Army (Brill Academic Publishers: Leiden, 2001), 114

Phillip Campbell, “Emperor Manuel’s Submission to Alexander III,” Unam Sanctam Catholicam, Nov. 29, 2024. Available online at https://unamsanctamcatholicam.com/2024/11/manuel-komnenos-submission-to-alexander-iii