In the distressed years surrounding the Second Vatican Council, there was considerable debate among the “experts” on how a Conciliar vision of Catholic spirituality ought to look. We are familiar with the debates over Marian devotion between the so-called “Minimalists” and “Maximalists,” the former who effectively sought to suppress Marian piety as hyper-sentimentalism and dangerous to ecumenical progress. A similar though less intense dispute arose over the propriety of the Sacred Heart devotions. The progressives insisted that this devotion was too bound up with Baroque era piety, meaning it suffered from a kind of sappy sentimentalism that was not suitable for the “noble simpliicty” envisioned for the modern Church. Furthermore, it was argued that it was not fitting for such a devotion to have such a central place in the Church’s life, since it sprung from a mere private revelation and was not integral to the Gospel message. In this article, we will endeavor to show that the Sacred Heart devotion is no mere Baroque sentimentalism, and that far from originating in some private revelation, it is a devotion whose origins are found in the deepest Traditions of the Faith.

Devotion to the Christ’s Heart in the Patristic Era

Pope Pius XII gave us a masterfully concise definition of the devotion in his encyclical Haurietis Aquas:

“Devotion to the Sacred Heart of Jesus, by its very nature, is a worship of the love with which God, through Jesus loved us, and at the same time, an exercise of our love by which we are related to God and to other men” (1)

The holy pontiff wrote these words at a time when devotion to the Sacred Heart was being attacked by the progressives as unbiblical, inappropriate for the modern day, and as constituting an inappropriate exaltation of the human nature of Christ. As we will see, the venerable Pius XII was entirely correct in insisting on the theological and practical fittingness of this devotion for the modern age.

The origin of the devotion can be traced back to the patristic era. In the pre-Nicaean age, the heart of Christ was identified with the streams of water which flowed from His side at the crucifixion. Being that these waters were associated with the sacraments, the reception of sacramental grace was seen as a “drinking” from the heart of Christ. For example, Hippolytus in the mid-3rd century wrote:

“The stream of the four waters flowing from Christ we see in the Church. He is the stream of living waters, and he is preached by the four evangelists. Flowing over the whole earth, he sanctifies all who believe in Him. This is what the prophet heralded with the words: ‘Streams flow from his heart.'” (2)

This living water is the source of grace for the Christian. Recalling the martyrdom of a deacon called Sanctus during the Great Persecution, Eusebius of Caesarea explains the martyr’s constancy as due to his refreshment at the Heart of Christ:

“[Sanctus] remained unbending and unyielding, strong in his confession of faith, refreshed and strengthened by the heavenly spring of living water which comes forth from the Heart of Christ” (3).

We can see in these writings an implicit devotional consciousness of the Heart of Christ as the source of grace. But it is during the post-Nicene era of the great Christological heresies that the devotion took on real form. This was largely in response to various heresies that attempted to exalt the divine nature of Christ at the expense of the human. For example, Apollinaris of Laodicea denied that our Lord possessed a true human soul as the principle of all human activity. The attacks of these Christological heretics thus gave momentum to the rightful exaltation of Christ’s human nature. This in turn led to further meditation and loving devotion centered on the blood and wounds of Christ, particularly His pierced heart. Thus, the devotion to the Heart of Jesus finds its true origin in the desire of the Church to properly exalt our Lord’s human nature.

In focusing on our Lord’s human nature, we see in the post-Nicene period a development of the idea of Christ’s heart as the source of human compassion and human virtue. The attributes we would desire of our own hearts—meekness, constancy, wisdom, humility—are all found perfected in the human soul of Christ, as exemplified by His heart. Eusebius of Caesarea, in his exposition of the prophet Isaiah, wrote:

“Christ was never severe with the weak nor showed harshness, even to the arrogant and proud. His heart always showed itself full of sweetness toward all men without exception. To all He showed with authority the things of God.” (4)

St. Augustine, writing at the end of the same century, explains that all of the spiritual gifts God wants to bestow upon a Christian can be found in the heart of Jesus. He who wants to possess all of these gifts and graces needs only to possess the Heart of Christ and he possesses all:

“Are not all the treasures of wisdom and knowledge hidden in Thee reduced to this, that we learn from Thee as something great that Thou art meek and humble of heart?” (5)

The Heart of Christ in the Middle Ages

Moving into the Middle Ages, we see that this truth has blossomed into a tender piety towards the humanity of Christ, and to His heart in particular, which is the source of all grace, inasmuch as it is the fountain from which God pours them out upon mankind. St. Anselm of Canterbury, not usually associated with devotional writing, nevertheless has extremely pious words about our Lord’s heart:

“What sweetness in this pierced side! That wound has revealed to us the treasures of His goodness, that is to say, the love of His heart for us.” (6)

In the same meditation, St. Anselm teaches that those who stay near to Jesus will receive the treasures of His heart, wherein are stored up all the goodness of God:

“Jesus, dear as He inclines His head in death; dear, in the extending of His arms; dear in the opening of His side. Opened so that there is revealed to us the riches of His goodness, the charity, that is, of His heart toward us.” (7)

While this is not fundamentally different from the language we have seen in the patristic era, the concept has become more universal in the early Middle Ages. By the turn of the millennium we begin to see the Sacred Heart as the object of special devotion in monasteries and devotional literature.

For example, a German devotional book from the 12th century contains the following prayer:

“Lord Christ, Son of God, for the dread with which you Sacred Heart was seized when you, Lord Christ, surrendered your holy limbs to suffering, and for your love and loyalty towards men, I beg you to comfort the pain of my heart, as you comforted the pain of your disciples in the days of your resurrection” [8].

As early as the 12th or 13th century, the Praemonstratensian St. Hermann Joseph penned the hymn Summi Regis Cor Aveto in honor of the Royal Heart of Christ. (9) The first verse reads:

Hail Heart of the Highest King.

I salute Thee with a happy heart;

To embrace Thee delights me;

This affects (touches) my heart,

that You allow me to speak to Thee.

There are numerous examples from the period, especially in German speaking lands. These devotional materials use the terminology “Sacred Heart” and encourage meditation upon the graces found in Jesus’ human heart. In the above cited prayerbook, we are still four centuries before St. Margaret Mary. Clearly this devotion did not begin with her private revelation.

St. Albert the Great and the Scholastics also encouraged devotion to the Sacred Heart, as well. In one of many passages on our Lord’s heart, St. Albert says:

“The water from His side and that which He poured from His heart are witnesses of His boundless love” (10).

The great Franciscan theologian St. Bonaventure could hardly contain himself when speaking on the glories of the Heart of Jesus:

“The heart I have found is the heart of my King and my Lord, of my Brother and Friend, the most loving Jesus…I say without hesitation that His heart is also mine. Since Christ is my head, how could that which belongs to my Head not also belong to me? As the eyes of my bodily head are truly my own, so also is the Heart of my spiritual Head. Oh, what a blessed lot is mine to have one heart with Jesus! …Having found this heart, both yours and mine, O most sweet Jesus, I will pray to You O’ my God” (11)

If we did not already know this text was from the middle of the 13th century, our progressive critics might mistake it for some “sentimentalism” of the late Baroque!

It is plain that the devotion to the Sacred Heart was present many centuries prior to Margaret Mary’s apparitions. But not only was the devotion itself present, but the symbolism we use today had already taken on recognizable form. The Sacred Heart is depicted in art as a heart with flames pouring forth from the top, a symbol of the intense, burning love with which our Redeemer loves mankind. Even this association of the Sacred Heart with fire is found in the Middle Ages. Consider the writings of the German mystic Meister Eckhart (d. 1327), who said:

“On the cross His heart burnt like a fire and a furnace from which the flame burst forth on all sides. So was He inflamed on the Cross by His fire of love for the whole world” (12).

St. Catherine of Siena, a Doctor of the Church and one of the most authoritative mystics of the Middle Ages, also symbolically described the Sacred Heart of Jesus as pouring forth fire:

“Put your mouth at the heart of the Son of God, since it is a heart that casts the fire of charity and pours out blood to wash away your iniquities” (13).

Nor was St. Margaret Mary the first to have a vision or mystical revelation of our Lord’s heart. St. Peter Canisius had a mystical revelation of the Heart of Christ in 1549, a century before St. Margaret Mary. The Jesuit saint of the Tridentine era recorded the specifics of his encounter with our Lord’s heart in detail:

“My soul fell prostrate before thee, my dull deformed soul, unclean and infected with many vices and passions. But thou, my Savior, didst open to me thy heart in such a fashion that I seemed to see within it, and thou didst invite me and bid me to drink the waters of salvation from that fountain. Great at that moment was my desire that streams of faith, hope and charity might flow from it into my soul. I thirsted after poverty, chastity and obedience, and I begged to be clothed and adorned by thee. After I had thus dared to approach thy Heart, all full of sweetness, and to slake my thirst therein, thou didst promise me a robe woven of peace, love and perseverance, with which to cover my naked soul. Having this garment of grace and gladness about me, I grew confident again that I should lack for nothing, and that all things would turn out for thy glory.” (14)

The late Middle Ages were a time of robust devotion to the heart of Jesus Christ.

By the 15th century, it was rare to find prayer books without any reference to the Sacred Heart of Jesus. Numerous meditations on the sufferings of the Sacred Heart were widespread, charaterized by their depth and mystical warmth. As an introductory prayer to the 15 Pater Nosters offered in honor of the passion of our Lord, German Catholics would pray:

“Lord, remember the tearing pain as your veins were torn from your heart and the spear penetrated your Divine Heart, so that you, Lord, may tear and break my heart from all things that could separate me from you.” (15)

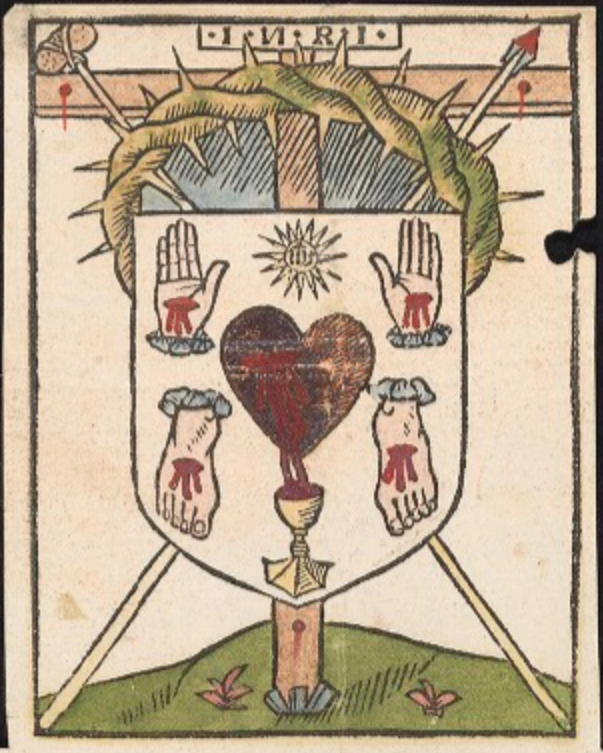

The late Middle Ages also saw the emergence of iconographical depictions of the Sacred Heart. The following English image, dating from around 1490-1500, depicts a familiar theme: the heart of Jesus bleeding into a chalice:

The image connects the Sacred Heart with the five wounds of Jesus, the traditional context for contemplation of His bleeding heart. It is believed to be the earliest artistic depiction of the Sacred Heart

Even in the decades immediately preceding the apparitions to St. Margaret Mary Alacoque, the Heart of Jesus as the symbol of God’s love for man and the source of all grace was a common theme in Catholic theology. St. Francis de Sales in his famous Treatise on the Love of God says that “God’s love is seated within the Savior’s heart as on a royal throne.” (16)

Sacred Heart Devotion: No Baroque Innovation

What, then, of the progressive critique that the devotion to the Sacred Heart is a relatively recent devotion based on a private devotion? Clearly the abundant testimony of the ante and post-Nicene Fathers as well as the medieval mystics, Scholastics, and Tridentine theologians contradicts this assumption. Devotion to the Sacred Heart goes back to the earliest centuries of the Church. Its theological foundation is extremely sound, being the focal point of the veneration of our Lord’s sacred humanity. Though not found explicitly in the Bible, the Fathers saw the devotion as steeped in biblical associations with the water that poured from Christ’s side at the crucifixion, the earliest association of the Heart of Jesus with grace. It is thus an integral component of the Catholic Faith and not a mere Baroque sentimentality, fit only for a more pious age but inappropriate today.

Thus, we ought to see the apparitions to St. Margaret Mary in 1673 in the same light as we see the definition of the Immaculate Conception in 1854: not as the creation of a new teaching or devotion, but as the formalizing or crystallization of a very potent devotional trend that had been present in various forms since the patristic age. Just as the progressives were wrong about Marian devotion, so are they wrong about devotion to the Sacred Heart. Thus, let us conclude with the words of the holy pontiff Pius XII, who teaches that devotion to the Heart of Jesus is the first step in spreading the Kingdom of Christ:

“…moved by an earnest desire to set strong bulwarks against the wicked designs of those who hate God and the Church and, at the same time, to lead men back again, in their private and public life, to a love of God and their neighbor, We do not hesitate to declare that devotion to the Sacred Heart of Jesus is the most effective school of the love of God; the love of God, We say, which must be the foundation on which to build the kingdom of God in the hearts of individuals, families, and nations” (17).

For further study, we recommend Heart of the Redeemer by Timothy O’Donnell, Foreword by Servant of God John A. Hardon, SJ. Click here to purchase the book from Amazon; it is only a few dollars used and a great resource on the theological and historical background of the devotion. Well worth the money and the read.

(1) Pius XII, Haurietis Aquas, 107 (1956)

(2) Hippolytus, Daniel, I,1

(3) Eusebius of Caesarea, Histor. Eccles. V.1,22

(4) Eusebius, In Isaim, XLII v.2-3

(5) Augustine, De Sancta Virginitate, 35

(6) St. Anselm, Liber Meditationem et Oratium, 10

(7) ibid.

(8) Timothy O’Donnell, STD, Heart of the Redeemer (Ignatius Press: San Francisco, 1992), 95

(9) https://www.deutsche-biographie.de/sfz30130.html. St. Hermann’s authorship is not certain; some also suggest this hymn was written by St. Bernard of Clairvaux as well.

(10) St. Albert, Sermon 27, De Eucharistia

(11) St. Bonaventure, The Mystical Vine, Ch. 3

(12) O’Donnell, 108

(13) St. Catherine of Siena, Letters, 97

(14) J. Broderick, St. Peter Canisius, (London: Sheed & Ward, 1938), 125

(15) Canon Dr. Médard Barth, “Zeitschrift für Aszese und Mystik” (1929), translated by Konstantin Staebler.

(16) St. Francis de Sales, Treatise on the Love of God, Vol. I, Book V, ch. 11

(17) Haurietis Aquas, 123

Phillip Campbell, “Devotion to the Heart of Christ Before St. Margaret Mary,” Unam Sanctam Catholicam, Dec. 29, 2013. Available online at https://www.unamsanctamcatholicam.com/2023/06/devotion-to-the-heart-of-christ-before-st-margaret-mary