One of the earliest engagements in the decade-long campaign to unify Italy under the House of Piedmont-Sardinia in the 19th century was the Piedmontese attack on Perugia in September of 1860. Perugia had been part of the Papal States since 1540 and was hence under the temporal administration of the papacy, at the time held by Bl. Pius IX. In 1859, however, revolutionary elements within Perugia had staged an uprising, temporarily throwing off the pope’s temporal power until Pius restored order with the help of the Swiss, retaking the city on June 20, 1859.

The papal recapture of the city was unfortunately accompanied by frightful massacres and atrocities, as the Swiss soldiers, unrestrained in their savagery, killed some 1,000 Peruginis. This slaughter would not soon be forgotten by the nationalist forces seeking to end the papacy’s temporal power in Italy. Perugia would subsequently be one of the first targets of King Victor Emmanuel II of Piedmont-Sardinia in his bid to unify Italy under his rule.

General Fanti’s Retaliation

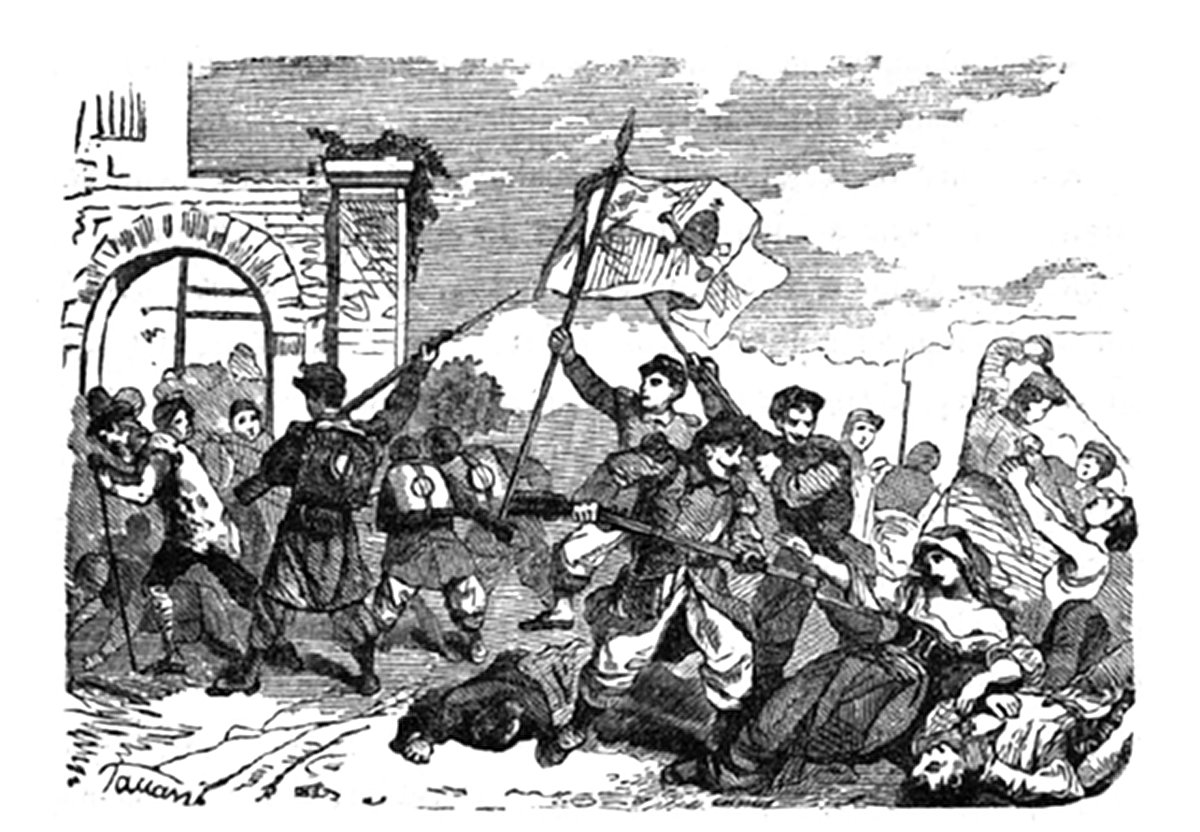

Retribution came in September 1860, when the Piedmontese army under General Manfredi Fanti—Victor Emmanuel’s Secretary of War—began the bombardment of Perugia. The Swiss garrison made a spirited attempt to defend the city, but were quickly overwhelmed by the power of the Piedmontese artillery. The Swiss retreated to the Rocca Paolina (Pauline fortress), a Renaissance-era fortification named for its patron, Pope Paul III. General Fanti thus entered the city, only the Rocca Paolina where the Swiss were holed up remained uncaptured. A truce was called so the papal troops and Piedmontese could negotiate a surrender.

The senior clergyman in the city at the time was none other than Joachim Pecci, the future Pope Leo XIII, who was Cardinal Archbishop-Bishop of Perugia. As the city’s handover to the Piedmontese was now inevitable, Cardinal Pecci’s job was to ensure the safety of Church property and personnel during the transition of power, inasmuch as possible. Unfortunately, among Fanti’s men were many rabid anti-clericalists who had no intention of respecting clerical property. While negotiations were pending for a suspension of arms, the Piedmontese seized the episcopal residence, the residence of the canons of the cathedral, and Cardinal Pecci’s seminary, under the allegation that bands of papal troops were finding a retreat there; gates and doors were broken open by the soldiers’ axes, and the main body of the advancing army posted their artillery forces in the porch of the cathedral and prepared to bombard the Rocca Paolina. The short truce ended, the bombardment commended. The humane entreaties of Cardinal Pecci and the mayor that the bombardment not be commenced were rudely repelled; of course, it only remained for the small garrison in the fort to capitulate, for if they returned the fire and resisted the assault, the city would become a scene of devastation. Before long the fortress fell; Schimdt, the leader of the Swiss, was carted off to Piedmont as a prisoner of war. The city was in the hands of General Fanti.

It would take Cardinal Pecci days to clear all the rubbish from the cathedral.

Fr. Baldassare Santi

One of Cardinal Pecci’s clerics was a priest named Baldassare Santi. A Perugian native born in 1821 and then 39 years of age, Don Baldassare had studied at Perugia’s Collegio della Sapienza Oradina. He was ordained a priest at the age of 22 and, in 1843, appointed parish priest of San Donato, a church located in the middle of the current Via Ulisse Rocchi, then called Via Vecchia.

The night the city was captured, September 14, Don Baldassare was arrested by the Piedmontese under an officer named De Sonntaz. He was charged with having killed the drum leader of the grenadiers, shooting him from the church while the former was approaching the building. Apparently, as the grenadiers stood about the front of the parish, a shot rang out from somewhere and the drum leader fell dead. The grenadiers shouted, “It was the priest!” They broke into the parish in a paroxysm of rage, where they found Don Baldassare hiding in a pile of firewood. They also claimed a warm rifle was found in proximity to the priest, which they claimed to be the murder weapon. Fr. Baldassare vehemently denied shooting the drum leader.

An improvised “court” was drawn up that very evening, presided over by one Colonel Gozzani and four other officers. Eyewitnesses were brought forward, testifying that the gunshot came from the rectory, and therefore the priest must be guilty. When it was objected that no one had actually witnessed Don Baldassare fire the fatal shot, it was responded that even had he not been the killer, he was undoubtedly an accomplice of whomever it was and thus still deserved punishment. As to why Don Baldassare was hiding if he was innocent, he replied that two religious sisters who were in the rectory advised him to hide himself when the church was broken into, as they suspected the grenadiers were after simple plunder when they entered the parish. It was they who suggested the priest conceal himself beneath the firewood.

Fr. Baldassare Santi was found guilty and sentenced to death that very night. General Fanti signed the death warrant, commenting that he wanted to make an example of Fr. Baldassare. As soon as the sentence was announced, the rectory was ransacked by looters who took away 2,500 lire belonging to the parish, along with silverware, linen, wheat, wine and wood. Oil and grain stores were spilled out along the way. None of the stolen goods were the property of Baldassare, but of the parish.

Cardinal Pecci’s Intercession

As soon as Cardinal Pecci heard of this outrage in the morning, he hastened to see General Fanti, but his intercession, even though it was accompanied with proofs of the rector’s good reputation for virtue and of his presumptive innocence, could not obtain even a suspension of the sentence of death or a review of the hasty findings of the court. More outrageous was the discovery that the murder weapon had not even been produced at the mock trial; in fact, no one could substantiate the claim that Don Baldassare was found with a firearm of any sort, the story of the warm rifle appearing to be mere rumormongering. Despite all this, General Fanti proved resolute. The sentence was to be a way of settling the accounts of the Piedmontese with the Church with Fr. Baldassare as a propitiatory immolation.

Don Baldassare Santi is Executed

On the morning of September 15, 1860, Fr. Baldassare Santi took communion, asked to read the breviary of the day, spoke to the religious sisters of the parish, and swore on the Blessed Sacrament that he was innocent. He was taken to Rocca Paolina, through the Corso Vannucci, a broad street through the heart of the old city center. The path to the gaol was filled with people who turned out just to hurl insults upon him. Being taken to the place of execution, the priest was permitted to read the Passion of Christ before facing the firing squad. Having finished reading the Passion of Christ, the priest kissed the image of the Crucified Jesus and said to the officer: “Thank you, I am ready.” The soldiers carried out the sentence, and Fr. Baldassare’s lifeless body collapsed on the ground of the fortress courtyard.

After the execution, the body was loaded onto a cart amidst the applause of the crowd. The place of Fr. Santi’s burial is not known. The trial documents were subsequently destroyed.

Incidentally, as a tragic postlude to the story, the two sisters who told Fr. Baldassare to hide were traumatized with the guilt of his death for the remainder of their lives. One of them eventually went mad and had to be admitted to the Santa Margherita Insane Asylum.

Modern Analysis of the Charges

Historians Maria Lupi and Count Luigi Rossi Scotti have demonstrated based on ballistics that it was impossible for the bullet that killed the drum leader to have been fired from the rectory window. The shot probably came from another window in Via Vecchia or from Piazza Ansidei, i.e. from the opposite side of the street. Assuming Fr. Santi was in the rectory complex at the time the shot was fired, he could not have been the killer. Furthermore, no murder weapon was ever produced.

Whatever the truth of the story, it is extremely likely that Don Baldassare Santi was the victim of a retaliatory killing by Piedmontese troops eager to make an example and strike a blow against the Church. The facts of the Baldassare Santi case have recently been compiled and examined exhaustively in Artemio Giovagnoni’s booklet, The Piedmontese Troops in Perugia and the Santi Case.

Phillip Campbell, “The Killing of Fr. Baldassare Santi,” Unam Sanctam Catholicam, June 2, 2024. Available online at https://unamsanctamcatholicam.com/2024/06/the-killing-of-fr-baldassare-santi