St. Junipero Serra (1713-1784) was a Spanish Franciscan missionary who played a pivotal role in founding the Spanish missions of California which would become the backbone of European settlement in the region. While he is best known for his evangelistic efforts in California, Fr. Serra spent two decades as a missionary in Mexico before he began his celebrated missions in the north. During his time in Mexico, Fr. Serra developed an evangelistic strategy centered on liturgical pageantry that would become a hallmark of his missionary work.

Fr. Serra in the Sierra Gorda

In 1750 Junipero Serra was still new to the Spanish Americas. Having arrived in Veracruz in 1749, he spent five months in the Franciscan missionary college of San Fernando in Mexico City before being entrusted with leadership of the Franciscan missions in the Sierra Gorda. The Sierra Gorda is a region north of Mexico City characterized by rugged, mountainous landscapes with steep slopes, deep canyons, and a wide diversity of climates. Today it is roughly contiguous with the Mexican state of Querétaro, but in Fr. Serra’s day it was the home of the Pames natives, a fierce tribe who had successfully resisted Spanish rule for centuries. Protected by strong natural barriers and secluded in their jagged mountain fastnesses, the Pames roamed the Sierra Gorda freely, occasionally venturing out to pillage nearby Spanish villages in the valleys. The Spaniards simply went around the Sierra Gorda in their subjugation of the land, leaving this mountainous region as an unsettled island in the midst of Spanish Mexico.

At the time, the Franciscans had made only nominal inroads into the Sierra Gorda. In fact, four priests sent there before Fr. Serra had all died in quick succession. But with the arrival of Fr. Junipero, the college’s guardian Fray Joseph Ortés de Velasco thought he had finally found the man to head up the mission to the Pames. Fr. Serra possessed a unique blend of talents: a penetrating intellect as a philosopher and theologian, a guileless, childlike disposition that would endear him to the natives, and a hardy constitution able to bear the rigors of missionary life in the Mexican backcountry. Serra was accordingly commissioned to go to the Pames and establish the missions in the Sierra Gorda on a firm foundation.

Fr. Serra and his companions arrived in the Sierra Gorda in mid-June, 1750, under escort of the Spanish soldiery. Serra came to the village of Jalpan, the home of the impoverished Franciscan mission in the Sierra Gorda. Jalpan was a settlement on the edge: barren and struggling, the mission church was a primitive structure of adobe and cane with a thatched roof. The people were poor and the land unproductive. On paper, the mission claimed one thousand parishioners among the Pames, but in realtiy Catholic life in Jalpan was anemic. Of the thousand Christian Pames, not a single one went to confession or Holy Communion even once per year, the bare minimum the Church requires of all Catholics. The mission structures were dilapidated and scarecly suitable for divine worship.

Fr. Serra and his companions had a substantial challenge ahead of them in Jalpan: to enkindle devotion among the region’s existing Catholics while spreading the faith to those not yet converted, as well as building up the physical infrastructure of the mission in the most desolate material conditions. It was a task that would tax Fr. Serra’s resolve to the fullest.

Fr. Serra’s Devotional Pageantry

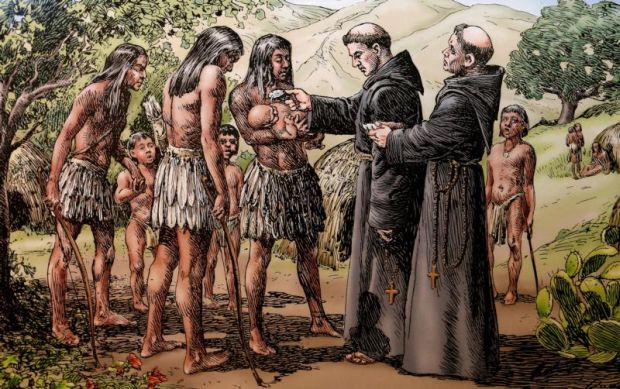

After prayerful reflection about the condition of the Jalpan mission, Fr. Serra decided that the way to draw the natives to faith was through the splendor of dramatic worship. Serra observed that the natives were impressed by pageantry, drama, and symbolism. He therefore determined on an evangelistic battle plan centered on bold, even ostentatious displays of piety that would cater to the natives’ inherent attraction to the theatrical.

Serra inaugurated his program with a bold gesture to persude the natives to return to confession and communion. One day after Mass, with the entire congregation present, Fr. Serra knelt before his companion Fr. Palóu and made a sacramental confession in front of the entire parish. The effect was stirring. “If the good padre needs to go to confession, who am I to abstain?” the Pames reasoned.

St. Junipero Serra would craft a liturgical year that accentuated the splendor of the liturgy. He believed that the visual representation of the faith was especially important to simple people like the Pames, counting on the sensory richness of Catholic piety to convert his people. During Advent, Serra created lavish Natvity Plays with the roles played by local children (this was in imitation of St. Francis, who had once converted the people of Greccio with his living Nativity plays). Lent was marked by high liturgies celebrated with as much pomp as Serra could muster given his limited resources, with the majority of his efforts going into the Holy Week liturgies. On Holy Thursday Serra would wash the feet of twelve elderly men from the congregation and then dine with them, afterwards preaching on the significance of the ceremony. The evening of Holy Thursday was the occasion of a lavish parade through Jalpan bearing the crucifix at the head of the procession. Serra also organized a similar procession for Good Friday, in which Christ’s descent from the cross and the sorrows of the Blessed Virgin were theatrically reenacted, with the roles of Christ and the Blessed Mother portrayed by the Pames. The principal feasts of Mary and the saints were the occasion of similar pageantry.

Serra also inaugurated the public recitation of the Stations of the Cross. Serra’s Stations were splenderous affairs, elaborate public processions led by the Franciscan padres and followed by the throngs of natives. After the procession, Fr. Serra would preach a sermon on the death of Christ on the hill of Jalpan within sight of the church. Between each station, Serra would carry a lifesize wooden cross upon his shoulders in dramatic imitation of Our Lord. This cross was no mere prop. Fr. Palóu—who was a decade younger than Serra and in the prime of life—reported that even he could scarecly lift it.

Saturday nights were the occasion of regular processions in honor of the Blessed Virgin Mary. These processions must have been magnificent, as Fr. Serra had taught the Pames to sing the prayers of the Rosary in their native tongue while carrying lanterns.

Fr. Serra’s Efforts Yield Abundant Fruits

Word of St. Junipero Serra’s impressive public devotions, drawing both natives and Spaniards to Jalpan to witness Serra’s services. The missions in Sierra Gorda were invigorated, yielding fruits both spiritual and material. The Pames repudiated their pagan goddess, Cachum, and demonstrated their sincerity by removing her idol from its hilltop shrine and giving it to Fr. Serra (who in turn presented it to the College of San Fernando for its archives). The spiritual life of the community was greatly enriched, which in turn enabled a fruitful relationship to blossom between the padres and the natives. Soon the Pames’ harvests were not only sufficient, but abundant. The impoverished region began to flourish. The population grew and living conditions improved drastically.

Junipero Serra would spend eight years in Jalpan. By the time he left in 1758, the meager adobe church had been replaced by the impressive Mission Santiago de Jalpan church, a massive Churrigueresque style structure that still exists today. The ornate church was funded by donations from the Pames made possible by the profits they had made from the sale of livestock and crops. The magnificence of Mission Santiago on display today is a testimony to the success of Fr. Serra’s program among the Pames.

Fr. Serra’s strategy of evangelization through lavish displays of pageantry would be used again with great success during his more well-known missionary adventures in Alta California. Fr. Junipero Serra’s time in the Sierra Gorda stands as a testament to the transformative power of faith wedded to ingenuity. Through his innovative strategy of evangelization—centered on the splendor of liturgical pageantry—he not only kindled devotion among the Pames but also forged a flourishing community from the ashes of a struggling mission.

I am indebted to the work of Don DeNevi and Noel Francis Moholy, whose scholalry book Junipero Serra (Harper Row, 1985) provided the details for this article. The relevant passages on Fr. Serra’s work in Jalpan can be found on pages 49-52.

Phillip Campbell, “Pageantry in the Missions of St. Junipero Serra,” Unam Sanctam Catholicam. May 30, 2025. Available online at https://unamsanctamcatholicam.com/2025/05/pageantry-in-the-missions-of-st-junipero-serra