The Catholic religion has always left in its wake monuments of great artistic and historical value. Cathedrals, paintings, statuary—all inspired by the Gospel and executed by men and women over the centuries whose love of God has left an enduring mark on human civilization. But while there have always been Catholic monuments, there has not always been a systematic study of these great emblems of faith. We are speaking here of the discipline of Christian archaeology. The father of Christian archaeology was the great Italian Giovanni Battista di Rossi (1822-1894). During his life, and largely because of his work, the piles of ruins scattered around Rome went from become curiosities for antiquarians to objects of serious archaeological inquiry. Di Rossi’s claim to fame is bound up with one of greatest and first discoveries of the age of Christian archaeology: the finding of the famous Catacombs of Callixtus.

The year was 1849. The great Di Rossi was at the time only twenty seven years old, and all of his greatest discoveries still lay ahead of him. He was not yet the foremost doctor of epigraphy in Rome or the father of Christian archaeology; in 1849 he was a mere clerk of the Vatican library with an interest in antiquities. Di Rossi’s job in the Vatican library was the cataloging of manuscripts, but in his personal time he was fond of wandering around the ruins of Rome and studying ancient Christian inscriptions. One day in 1849, Di Rossi happened to poking around a rubbish pile on the Appian Way about an hour outside Rome. There he found a marble slab with the inscription NELIUS MARTYR. The slab was discovered in a long abandoned chapel that had once been dedicated to the martyr Pope Zephryinus but which was then being used as a tool shed. The shed-chapel was situated in a large vineyard.

Having never heard of a martyr by the name of Nelius, De Rossi was puzzled – until he surmised that the inscription was most likely incomplete, and that the completed inscription ought to read [Cor]NELIUS MARTYR. If this reading was accurate, he was holding in his hands an ancient inscription from the tomb of the martyr Pope St. Cornelius (d. 253).

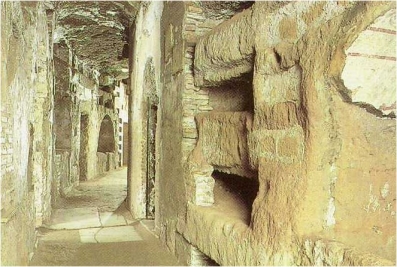

Using a combination of scholarly knowledge and a hunch, he reasoned that this slab of marble had not been moved too far from its original location and reasoned that the tomb of the martyr was somewhere in the vicinity. His natural conclusion was that the vineyard – enclosed within a sharp angle formed by the Via Appia and the Strada della Sette Chiese – actually sat over a hitherto unexplored cemetery. This deduction was verified when Di Rossi found a light shaft near the old chapel of Zephryinus which led down into a series of corridors.

Going back to his manuscripts, Di Rossi knew that Pope Cornelius was supposed to be buried in this vicinity in a cemetery which the ancient Christians referred to as the cemetery Callixtus, but which had not yet been discovered. If this vineyard did indeed contain the catacomb Callixtus, this was a particularly exciting prospect, as Di Rossi knew that the ancient sources all agreed that the tombs of many of the eminent popes of the third century were located there.

Unfortunately, the property was privately owned. The only one with the resources and the clout to push such a purchase through and get excavations going was none other than Bl. Pius IX himself. Di Rossi knew Pius from his work in the Vatican Library and had a personal interview with Pio Nono in which he detailed his discoveries and begged the Holy Father to purchase the property. Pius IX was a joker by nature and took pleasure in chiding the zeal of Di Rossi, who was apparently a very high strung sort of fellow. The humorous pontiff feigned little interest in the project, told Di Rossi he must be imagining things, and led him on to believe he would not support the project. Finally, after the audience came to an end, Pius IX told his aid, Monsignor Merode, “I’ve chased Di Rossi like a cat, but I will buy the vineyard.” (1)

How overjoyed Di Rossi was to find that Pius IX had purchased the vineyard and given Di Rossi authority to conduct excavations! Excavations began at once, and all Di Rossi’s expectations were fulfilled. He found the missing part of the slab with the phrase COR, as well as another which read EP, so that the completed inscription read CORNELIUS MARTYR EP [iscopus]. He also discovered the chapel tomb of St. Cornelius itself. But that was only the beginning of the marvel.

As excavations continued, Di Rossi uncovered the tombs of nine pontiffs, including Pontian, Anterus, Fabian, Lucius I and Eutychian. In the far wall was entombed the martyr Pope Sixtus, killed during the persecution of Valerian. In a crypt adjoining the papal tombs Di Rossi uncovered the original tomb of St. Cecilia (Cecilia’s relics had been removed in the 9th century); the tombs of the pope saints Miltiades, Gaius and Eusebius were uncovered in subsequent excavations, as were the crypts of the martyrs Calogerus and Parthenius, the double cubiculum of Severus, and the tomb of Pope St. Marcellinus. A treasure trove of Christian art was discovered as well, including frescoes in the Byzantine style, decorated sarcophagi, and depictions of the Good Shepherd and images of loaves and fish dating back to the time of Marcus Aurelius. Eventually, Di Rossi would conclude that the cemetery he had stumbled upon by accident had at one time contained the tombs of sixteen popes and fifty martyrs buried in 12 miles of corridors. The earliest papal burial in Callixtus was that of Pope Anicetus (r. 155-166); the last was that of pope Damasus (366-384), whose empty sarcophagus was found in the catacomb.

New of Di Rossi’s discoveries aroused considerable enthusiasm throughout Italy. After a time, Pius IX himself decided to come view the site and see the papal crypts for himself, although personally he seemed skeptical that the catacomb contained as many treasures as Di Rossi claimed. At breakfast the day he came to visit the site, he told his aides that “Archaeologists are dreamers and poets. They weave together so many fantastic ideas that ordinary mortals can’t even understand them.” (2) Di Rossi, who was present at the papal breakfast and overheard the comment, kept his peace. He would let his discoveries speak for themselves.

During his visit to the subterranean galleries and crypts, Pius IX was moved deeply. The reality of what Di Rossi had found slowly overcame him. When Di Rossi showed him some inscriptions from a third century papal tomb which he had reconstructed, tears welled up in the eyes of Pius IX, who asked, “Are these really the tombstones of my predecessors who were buried here?” Di Rossi could not stop himself from paying the pope back for his earlier jests. “It’s all a hallucination, your Holiness,” Di Rossi said. “Di Rossi,” Pius retorted while gazing in awe at the tombs, “you are a rascal!” (3)

The Catacomb of Callixtus was certainly not the last discovery Di Rossi was to make in his long and illustrious career, but it was certainly the most important. Pius IX, a scholarly pope with a love of Christian antiquities, knew how important the physical monuments of the saints and martyrs are to the life of the Church, as they help establish that living historical bond between ourselves and the renowned progenitors of our holy religion. The tombs and galleries of the catacombs become aids to faith, and their art and inscriptions become doorways into the thought, discipline and beliefs of the earliest Christian communities.

Di Rossi, who died in 1894, would go on to catalog over 12,000 catacomb inscriptions, which provide a source of immense knowledge about Christianity during the earliest centuries. Unfortunately, none of Di Rossi’s work has been translated directly into English, but one of Di Rossi’s disciples, Fr. James Spencer Northcote, did produce an English summation of Di Rossi’s most important insights in a splendid work titled Epitaphs of the Catacombs: Christian Inscriptions in Rome During the First Four Centuries. Published in 1878 at the height of Di Rossi’s career, Northcote’s book pulls together the historical, spiritual and apologetical value of Di Rossi’s finds, together with scores of illustrations, to be the most exhaustive study of the catacombs in the English language. It is an invaluable resource for anyone interested in learning more about the Roman catacombs.

(1) This quote and all of the material for this story is taken from The Roman Catacombs and Their Martyrs by Kertling and Kirschbaum, translated by Joseph Costelloe, SJ (Bruce Publishing; 1956). The tale of Di Rossi’s interview with Pius IX can be found on page 8.

(2) Ibid.

(3) Ibid., 8-9

Phillip Campbell, “Di Rossi Finds the Catacombs of Callixtus,” Unam Sanctam Catholicam, March 23, 2014. Available online at http://unamsanctamcatholicam.com/2022/05/de-rossi-finds-the-catacombs-of-callixtus