What do Catholics believe about the Virgin Mary? In this essay we will go back to the basics of Catholic Mariology, with an aim towards explaining Catholic beliefs about the Blessed Virgin Mary to a Protestant audience. Catholic Mariology has traditionally been a fundamental obstacle to Protestant acceptance of the Church’s claims. For many Protestants, every other Catholic teaching can be accepted with the proper education and the working of grace. But aversion to the Catholic veneration of Mary is so strongly ingrained in Protestant tradition as to be extremely difficult to overcome for some Protestants, even when they positively will to join the Catholic Church.

It is not possible to treat every aspect of Mariology in an article like this; in many places, our treatment of the issue will be cursory and will refer the reader to other sources. We will progress along the following outline:

I) Theology of Marian Veneration

a) Definitions

i. Communion of Saints

ii. “Veneration” and “Adoration”

b) Rationaleof Marian Devotion: Divine Maternity

II) Biblical Background

a) Old Testament

b) New Testament

III) Patristic Considerations

a) Ante-Nicene

b) Post-Nicene

IV) Developments in Theology and Devotions

a) Theology: Four Marian Dogmas

b) The Propriety of Marian Devotion

V) Glorification of Mary

I. THEOLOGY OF MARIAN VENERATION

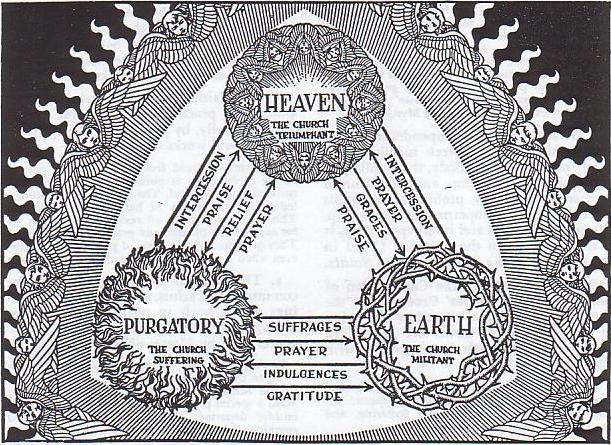

In the Communion of Saints

What does it mean to offer “veneration” to the Blessed Virgin Mary? Understanding Marian veneration depends in a large part upon understanding the doctrine of the Communion of Saints. The Communion of Saints is the idea that the Church exists in three states: the Church Militant, Church Suffering and Church Triumphant, encompassing those believers who are on earth, in purgatory and in heaven. Since there is only one Church, the Church remains one despite its existence in these three states. Therefore, all the members of the Church are capable of sharing in spiritual goods and graces. The fact of physical death is no barrier to this; just as Christ overcame death by His perfect love, so in Christ death is no longer a barrier for the believer. We can pray for one another on this earth, and in the Spirit, pray for those in purgatory, as well as solicit the prayers of those members of the Church already in heaven, whether they be saints or angels. The interrelationship of the Church in her three states is illustrated aptly in this picture:

St. Thomas Aquinas explains the dogma this way:

“We must also know that not only the efficacy of the Passion of Christ is communicated to us, but also the merits of His life; and, moreover, all the good that all the Saints have done is communicated to all who are in the state of grace, because all are one: “I am a partaker of all them that fear Thee.”[Ps 118: 63] Therefore, he who lives in charity participates in all the good that is done in the entire world; but more especially does he benefit for whom some good work is done; since one man certainly can satisfy for another. Thus, through this communion we receive two benefits. One is that the merits of Christ are communicated to all; the other is that the good of one is communicated to another.” (1)

A good introductory book that helps Protestants get an understanding of the Communion of Saints is Patrick Madrid’s work Any Friend of God’s is a Friend of Mine, but it is easiest to see the Communion of Saints as the practical implication of Christ’s teaching that the Church is one, and that this oneness is the very oneness that the Son and the Father share (cf. John 17:21). Death cannot disrupt this oneness anymore than death was able to keep Christ in the tomb.

Veneration and Adoration

So members of the Church Militant (us on earth) are capable of having communication in grace with the members of the Church Triumphant (those in heaven). When dealing with the various types of communication the Church has between its three states, it is important to get some terminology correct. When we petition for the intercession of the saints in heaven, we are venerating them. This is because our petition is, in a sense, a two-fold act: in the first place, we rejoice in what God’s grace has wrought in the saint and honor the saint for their virtues; second, by virtue of what God has made of that saint in grace, and by the union we have with them in the Communion of Saints, we ask their intercession for a particular intention. We do not recognize them as the ultimate source of our blessings, but as a means to obtaining graces from God. Furthermore, we understand that to the degree that they are empowered to answer our petitions, that in itself is a work of God’s grace, that it is God Himself who has placed them in that position of authority, as “we shall also reign with Him” (2 Tim. 2:12).

Therefore, the veneration is not absolute, but relative, and this relative veneration has gone by the name dulia in Catholic Tradition and is best defined as the reverence that is due to saints and angels. This is to be distinguished from the adoration which is due to God alone and which goes by the name latreia, which is best defined as an act of worship offered to God in acknowledgment of His supreme perfection and dominion, and of the creature’s dependence upon Him. So the honor accorded a saint is different from the honor accorded to God not only in degree but in kind as well.

Therefore, any saint who is reverenced, venerated, honored or petitioned is done so in a relative manner (dulia), while the honor due to God (latreia) is absolute.

Rationale of Marian Devotion: Divine Maternity

So it is a good and praiseworthy thing for the members of the Church on earth to have recourse to the prayers of the saints in heaven and the graces obtained therefrom. Marian devotion is nothing other than the same principle applied to one saint in particular (the Blessed Virgin Mary) by virtue of her special relationship and intercessory power with God.

But does the Blessed Virgin, in fact, possess some special relation and intercessory power before God different than any other saint or angel?

Catholic Tradition unanimously answers in the positive, due to the fact that her relationship with Christ is fundamentally different than that of any other creature. While all believers are united to Christ in the Holy Spirit, Mary alone had a union with Christ that was physical. She physically bore God the Son in her body for nine months, nourished Him at her breast, raised Him in her home, and continued with Him His entire life all the way to the Cross. No other person had such intimate contact with our Lord as Mary did. Her relationship with Him was truly motherly, and inasmuch as Christ was God the Son, truly is Mary called Mother of God. We will not here debate the propriety of calling Mary “Mother of God”; for more on this title, Catholic Answers has a pretty good tract here.

Mary was called to be the earthly mother of God the Son. Every other prerogative the Church attributes to her flows from this fact of her Divine Maternity and is merely an extrapolation of this fundamental dogma.

II. BIBLICAL BACKGROUND

Old Testament

This Divine Maternity was not incidental; it was something preordained from the very beginning of salvation history. Let us recall God’s original words to the serpent, “And I will put enmity between you and the woman, between your seed and her seed; you shall strike his heel, but He shall crush your head” (Genesis 3:15). The antagonism between the Woman and the Devil goes back to the beginning, as well as the prophecy that the Seed of the Woman would crush the head of the Devil. Now, the son of Eve did not crush the head of the devil; this prophecy referred to a time far off, when the New Eve, Mary, would bear a Son who would crush the serpent’s head forever.

This is also why in every story in the Old Testament in which a woman defeats a stronger, male aggressor, she does so by crushing his head; see here for more on this phenomenon. There woman-heroes are types of Mary, the Woman whose Seed destroys the head of the devil.

Another important insight into Mariology comes from the episode of Solomon and Bathsheba in 1 Kings 2. In this passage, Bathsheba, mother of Solomon, is established as Queen Mother of ancient Israel and has a throne set up for her at the right hand of the king (1 Ki. 2:19). This signifies Bathsheba taking on the formal office of Queen Mother in the kingdom of Solomon, for in ancient royal houses where a king may have had dozens, even hundreds of wives (like Solomon), the Queen was not the wife of the king but his mother. This office of Queen Mother is mentioned many other places in the Old Testament (1 Ki. 15:13, 2 Chr. 15:16), and every time a king of Judah or Israel is mentioned in the Book of Chronicles, the sacred author takes care to point out who his mother was.

The import of this is that the Davidic Kingdom of ancient Israel was ruled by a series of kings (sons of David) at whose right hand sat a Queen Mother. She was an important person in the royal house and was seen as an intercessor with the king (1 Ki. 2:13-18). In the New Testament, Christ is the true Son of David, the heir of the Kingdom of David, and even as the Davidic kingdom of old Israel had kings from the line of David and Queen Mothers in the royal household, so the Messianic kingdom is ruled by the Son of David who has the Queen Mother at his right hand.

This identification of the Virgin Mary as the Queen Mother is well established in the Church’s tradition and liturgy and is the reason why Psalm 45—”at your right hand stands the queen in gold of Ophir” (v.9)—is read on the Feast of the Assumption.

Thus the Old Testament is replete with types of the Blessed Virgin, both as the New Eve whose Seed will destroy the serpent, as well as the Queen Mother who sits beside the throne of the Son of David. Both types shed light on the role of Mary in the New Covenant.

New Testament

An exposition of New Testament Mariology is probably beyond the scope of this article, but it is sufficient to note two points for further study: (1) The implications of Mary’s sinlessness from the angelic greeting in Luke 1, and (2) Mary’s close connection with the Holy Spirit.

In Luke 1, Gabriel greets Mary with the phrase “Hail, full of grace,” or in Greek, Chairō, Kecharitomene. This greeting signifies that Mary is superior to the angel, but also that she has been perfected in the grace of God, which is why Kecharitomene is so frequently rendered as ‘full of grace’. Please see here for a much more thorough treatment on the meaning of the phrase Chairō, Kecharitomene.

This “fullness” of grace has always been understood in Catholic Tradition to mean that Mary is perfected in God’s grace—i.e., that she is without any trace of sin and is overflowing with God’s grace in an exceptional manner. While it may not have been strictly necessary, this divine favor was fitting, seeing as Mary was the vessel who bore God the Son in her womb. Here we see a connection with the ceremonial of the Old Covenant: Just as it was fitting that the Ark that carried the word of God on stone in the Old Testament should be covered with gold within and without, so it is fitting that the new Ark that carried the Word of God made flesh should be all pure within and without. Hence, the traditional teaching that Mary is completely sinless, both of actual and original sin, what Catholics call Mary’s privilege of being immaculately conceived.

Protestants will often argue that this was unnecessary, as Christ could have been brought forth perfect, divine, and sinless without necessitating an Immaculate Conception of Mary. The Church’s Tradition argues in favor of the Immaculate Conception based not on necessity, but on fittingness. For much more on the rationale for the Immaculate Conception and the concept of fittingness, please see this article from the Unam Sanctam Catholicam blog.

Note that, as we mentioned above, Mary’s Immaculate Conception and her subsequent sinlessness are founded upon her Divine Maternity—her mission of being God the Son’s mother on this earth.

It is also worth noting that Mary is very closely bound with the Holy Spirit in the New Testament. In Luke 1, the Incarnation is effected by the Holy Spirit. When Mary visit’s Elizabeth, it is the Holy Spirit that causes John the Baptist to leap in his mother’s womb; on the day of Pentecost, when the Spirit is poured out upon the Church, vivifying it and causing it to become the Mystical Body of Christ, Mary is there in the midst of the Apostles. In short, whenever Mary shows up, the Holy Spirit shows up as well. This is because, being sinless and full of grace, she is in constant communion with God through the Spirit and perfectly mediates the Holy Spirit. This is why Tradition calls her “spouse of the Holy Spirit” and why her intercession is so powerful; in her perfect submission to God’s will, she is the perfect daughter of God the Father; in her intimate union with the Spirit, she is rightly called His spouse; in bearing the Son of God, she is Mother of the Son: Daughter, Spouse, Mother. Her union with the Trinity is profound, and therefore her intercession with God is powerful.

III. PATRISTIC CONSIDERATIONS

Ante-Nicene Fathers

It is not feasible for us here to explore the full development of Mariology in the patristic period, either ante- or post- Nicene, although we will mention a few of the more famous citations. The importance of the Church Fathers here cannot be understated; the Fathers reveal to us how the earliest generations of Christians thought about the Blessed Mother, and the seeds of patristic Mariology would blossom forth into a fuller exposition of Marian dogma during the medieval period. Thus there is a continuous line of development from the Fathers to the medievals to the early modern and modern Mariological teachings in Catholicism.

In the ante-Nicene period, we see three main developments in Mariology: (1) Mary as the New Eve (2) the sinlessness of the Blessed Virgin, and (3) Mary as the Mother of God (this conception comes later, during some of the early Trinitarian controversies and is not definitively defined until the post-Nicene period. A famous passage comes from St. Irenaeus of Lyons (c. 180), who wrote of Mary:

“[Eve] having become disobedient, was made the cause of death, both to herself and to the entire human race; so also did Mary, having a man betrothed [to her], and being nevertheless a virgin, by yielding obedience, become the cause of salvation, both to herself and the whole human race…The knot of Eve’s disobedience was loosed by the obedience of Mary. For what the virgin Eve had bound fast through unbelief, this did the virgin Mary set free through faith.” (2)

Thus, from an early time, Mary was seen as the antitype of Eve, who through faith worked salvation whereas Eve, through unbelief, worked death. A connection is established between Eve’s virginity and Mary’s virginity, and a contrast between Mary’s faith and Eve’s lack of faith; a connection was also made between the sinlessness of Eve (originally) and the sinlessness of Mary, and the freedom of Mary from any sin is well established in the ante-Nicene period. Thus, references to Mary as “pure” and “stainless”, much of these coming from devotional poetry. For example, this hymn from the Coptic Church of Alexandria, c. 250:

“Beneath thy tenderness of heart

we take refuge, O Theotokos,

disdain not our supplications in our necessity,

but deliver us from perils,

O only pure and blessed one.” (3)

The core of Mariology is present here; Mary understood as Theotokos (Mother of God), her eminent blessedness above other saints, her unique purity (“O only pure”), denoting sinlessness, and finally, by virtue of all of these, her power as an intercessor before God.

We could give many more ante-Nicene examples, but these are sufficient to show the fundamental tenets of Mariology are firmly established prior to Nicaea.

Post-Nicene Fathers

In the post-Nicene Fathers, we see a further development of Mariology as the concepts of the ante-Nicene period are unwrapped with all their implications. For example, belief in Mary’s Assumption into heaven, which is implied in the dogma of Mary’s sinlessness; for more on how the doctrine of sinlessness implies the Assumption, see here. It is not unnatural that this great flowering of dogma should happen with the legalization of Christianity; there was a general blossoming in all categories of theology during the 4th century, as Christians finally had the luxury of working out the implications of their beliefs in the open without having to worry about being imprisoned or killed. In the decades immediately following Nicaea, we see testimonies of the Perpetual Virginity of Mary (see here) and the further development of her public devotion and private veneration. The increase of devotion to Mary followed upon the declaration of the Council of Ephesus (431) that Mary should be venerated as Theotokos, Mother of God.

IV. DEVELOPMENT OF THEOLOGY AND DEVOTIONS

The Four Marian Dogmas

As the ancient world gave way to the Middle Ages, we see that the corpus of the Church’s Marian teachings crystallized into what are called the Four Marian Dogmas. These dogmas are: Mary’s Divine Maternity, her Immaculate Conception, her Perpetual Virginity, and her Immaculate Conception. The fact that two of these dogmas (Immaculate Conception and Assumption) were not formally defined until relatively recently (1854 and 1950, respectively) is a source of confusion to many non-Catholics, who assume the definitions of the papal extraordinary Magisterium constitute the date the dogmas were “invented” or when they became part of Catholic teaching. In fact, as we have seen, these dogmas were all present in Catholic teaching for many centuries, sometimes back to the ante-Nicene period. They were all believed by all Christians throughout the Middle Ages. With the solemn definitions of 1854 and 1950, the popes proclaimed that the teachings of the Immaculate Conception and the Assumption belonged to the deposit of faith (depositum fidei); i.e., that they are part of divine revelation, and therefore must be definitively held by all Catholics. Prior to the definitions, there had been some discussion as to whether these teachings were actual dogmas of the faith or whether they were certain theological opinions—that is, teachings whose authority is not part of divine revelation but are bound up with divine revelation.

Propriety of Marian Devotion

Thus, we see a smooth and continuous development of Mariology from the teachings of the Church Fathers on her sinlessness and perpetual virginity through the Middle Ages and on into the modern period. Marian dogma has been central to the development of Christianity.

And, following the principle lex orandi, lex credendi (the law of prayer is the law of faith), the development of Marian dogma spawned a vast and rich tradition of Marian devotion. Thus, it is not sufficient to simply give assent to the Church’s teachings on Mary if one cannot bring oneself to appropriate these teachings into one’s own spiritual life and derive benefit from them. This is why the Church has always encouraged Marian devotions as proper to the Christian life.

Because of Mary’s privileged status, she has a unique intercessory power. We mentioned above that the devotion and veneration of the saints is referred to as dulia, whilst the adoration of God is called latreia. The veneration due to Mary as the greatest of all the saints and the most perfect of all God’s creations is called hyperdulia, which both reaffirms that the veneration of Mary is ultimately the veneration of a creature, not God, as well as that the veneration of Mary is higher than that due to any other saint or angel by virtue of her absolutely unique position in relation to God, Christ and the Holy Spirit. There is no more powerful intercessor than Mary, and in knowledge of this, Christians have not hesitated to invoke her by means of a rich variety of traditions: the Rosary, the Little Office of the Blessed Virgin, May crownings, the Brown scapular, the Green scapular, the Miraculous Medal, the Perpetual Help devotions, and so on.

It could also be mentioned, as recent papal Magisteriums have emphasized, Mary’s value as a role model. In the manner in which she has perfect faith in God’s promises despite the apparent impossibility of their fulfillment on a natural level, she perfectly embodies the faith of Abraham and is a model of Christian faith. In the manner in which she keeps God’s word in her heart and ponders it (Luke 2:19) she is the model of contemplation; in her journey with Christ to the cross she models Christian suffering, for when we suffer we do so with and in Christ our Lord, and in being taken into the home of the Beloved Disciple (John 19:26-27), we are shown that if we would be beloved disciples, we too, ought to take Mary into our home, for as to us as much as to St. John, our Lord says, “Behold, your mother!” Thus, there is a great propriety in devoting ourselves to Mary, and all of the saints recommend devotion to Mary as the surest way to holiness.

V. GLORIFICATION OF MARY

St. Bernard of Clairvaux, one of the greatest theologians of the Middle Ages who was renowned for his love of the Blessed Mother, coined the phrase, De Maria Nunquam Satis, translated, “About Mary, one can never say enough.” As the mysteries of her life and the graces given to her are wrapped up with the very Incarnation itself, it is impossible to exhaust the richness of her life and destiny. It is important to acknowledge, as the popes do and as the famous Marian saint, Louis de Montfort does, that Marian devotion is not an end in and of itself. Only God is worshiped for His own sake. Mary is venerated as a means of bringing us closer to Christ and making us more Christlike. One may question why one “needs” to go through Mary to get to Jesus; it can be retorted that one does not “need” to so much as one ought to, and that this must be grounded in the larger context of the communion of saints to have a proper understanding of it. The saints and angels are means of grace to us, and Mary in an exemplary way. They do not stand between us and God; rather, they facilitate a more perfect union between us and God by their intercession, and among the members of the Church themselves.

For further reading on Marian devotion, I highly recommend the classic work by St. Louis de Montfort, True Devotion to Mary, available here on Amazon.

O Virgo splendens, hic in monte celso

Miraculis serrato fulgentibus ubique,

Quem fideles conscendunt universi.

Eia pietatis oculo placato

Cerne ligatus fune peccatorum

Ne infernorum ictibus graventur

Sed cum beatis tua prece vocentur.

O resplendent Virgin,

here on the miraculous

mountain cleft everywhere

by dazzling wonders,

and which all the faithful climb,

behold them with your merciful eye of love.

(14th Century Hymn from Montserrat, Barcelona, Spain)

NOTES

[1] Catechism of St. Thomas Aquinas, Sec. 1, Art. 10

[2] Adversus Haeresies, Book III, Chap. 22, 4

[3] John Ryland’s Papyrus #470, available online at: http://theoblogoumena.blogspot.com/2007/08/john-rylands-papyrus-470.html

Phillip Campbell, “Fundamentals of Mariology,” Unam Sanctam Catholicam, October 24, 2013. Available online at http://unamsanctamcatholicam.com/2022/06/fundamentals-of-mariology