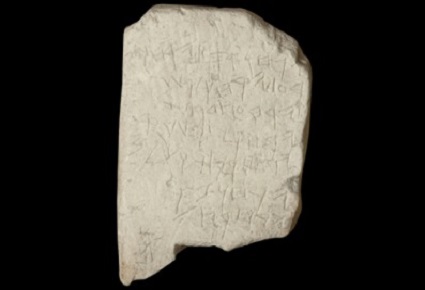

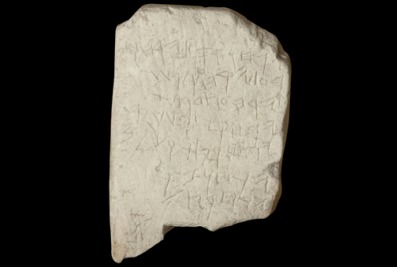

In excavations carried out in 1908 in the city of Gezer, twenty miles west of Jerusalem, Irish archaeologist R.A.S. Macalister unearthed a limestone tablet containing seven lines of inscription written in a script that is known as paleo-Hebrew. Subsequent investigation revealed that the tablet was a sort of rudimentary calendar of the agricultural year, beginning with the Israelite month of Tishri. The name Abijah appears vertically on the side of the tablet, probably indicating name of the tablet’s owner. The calendar was dated to the middle 10th century B.C., probably during Solomon’s reign, when Gezer was under the control of the Israelites (1 Kings 9:16). To date, the Gezer Calendar is the earliest extant example of a Hebrew inscription and is an important piece of evidence in the debate surrounding the Documentary Hypothesis of the form critics.

The calendar goes through each of the Hebrew seasons and designates what agricultural work is proper to each. Roughly translated, the text of the Gezer Calendar reads:

Two months gathering [September, October]

Two months planting [November, December]

Two months late sowing [January, February]

One month cutting flax [March]

One month reaping barley [April]

One month reaping and measuring grain [May]

Two months pruning [June, July]

One month summer fruit [August]

Scholars debate the meaning of the calendar, but a commonly accepted view is that this is a schoolboy exercise and that “Abijah” is the name of the student to whom the tablet belonged. Experts in ancient epigraphy presume it is the work of a child because of the wide, almost sloppy script. This suggests it was an exercise in engraving, perhaps from an apprentice in stone masonry.

As mentioned above, the script is something called paleo-Hebrew. Paleo-Hebrew is a predecessor to the classical Hebrew of the latter Jewish kingdom and is derived from the Canaanite alphabet of Phoenicia that originated in the mid-second millennium B.C. It represents a phase in the development of the Hebrew script when it had broken off from Phoenician but still retained many important similarities, not unlike the difference between classical Latin and the vulgar Latin of late antiquity.

The Gezer Calendar is important because it testifies to the veracity of the Biblical narrative on several points. First, the historical reality of the United Monarchy, which many modern historical form critics deny. Gezer was a Canaanite city for most of its existence; yet in 1 Kings 9:16 we read that the Pharaoh of Egypt—probably Pharaoh Siamun—had “come up and captured Gezer; he destroyed it by fire, killed the Canaanites who dwelt in the town, and gave it as dowry to his daughter, Solomon’s wife.” Thus Gezer became an Israelite city in the period shortly before the Calendar was carved, which would explain the presence of Hebrew writing in what had, until then, been a Canaanite city. The narrative of 1 Kings and these details of the early years of Solomon’s reign are thus verified.

Also the name of the person who owned the tablet, “Abijah”, is a common Hebrew name of the 10th century. In fact, Abijah was the name of both the son of Jeroboam and the grandson of Solomon (1 Kings 14:1, 1 Ch. 3:10), both also living in the middle-to late 10th century The name on the tablet thus serves as a further verification of its origin in the time of Solomon.

But most importantly, the Gezer Calendar attests to the widespread use of writing in ancient Israel. According to the modernist Documentary Hypothesis, writing was a late development in Israel, not present until the 8th century at least. Yet in the Gezer calendar we see that not only was writing present in Israel as far back as the time of Solomon, but that it was widespread enough that it was being taught to children. In other words, Israelite society of the early United Monarchy was highly literate.

Some scholars debate the the Calendar is a schoolboy exercise and suggest it might be a tool for collection of taxes from farmers. This would further strengthen the case for the appearance of writing early among the Israelites, as it suggests that by the middle 10th century the kingdom already possessed a highly literate bureaucracy capable of complex accounting—complex at least relevant to that age. Like the existence of the massive 11th century fortress of Khirbet Qeiyafa, this would attest to the power and centralization of the Israelite monarchy under David and Solomon, a far cry from the scattered band of nomadic raiders envisioned by the form critics.

Writing does not develop and permeate a society overnight. Whether schoolboy exercise or tax collector’s aid, the Gezer Calendar testifies to the early existence and wide diffusion of writing in Israelite society at least back to the turn of the 1st millennium and probably earlier.

Phillip Campbell, “The Gezer Calendar,” Unam Sanctam Catholicam, September 4, 2014. Available online at http://unamsanctamcatholicam.com/2022/06/the-gezer-calendar