If one were to have a basic literacy of the most important dates in the history of Christendom, undoubtedly Christmas Day of the year 800 would take pride of place. This was the date that King Charles of France was crowned Emperor by Pope Leo III. This event was of pivotal importance in both the history of Europe and of the Catholic Church. It is probably the single most important moment in Europe between the Fall of Rome and the Protestant Revolt, as it established Italy and the Papal States as parts of western Europe, made Charlemagne the most renowned king of the Middle Ages, and was fundamental in creating the contours of medieval and even modern Europe. In this article, we will examine the background of Charles’ coronation, Pope Leo’s motivation in offering him the imperial crown, and the short and long term results of the translation of the imperial title to the West. Indeed, there have been view events in European history with such far-reaching consequences.

The Imperial Title in the West

It was the Roman Emperor Diocletian (285-305) who first divided the Roman Empire into two halves, East and West—or, more specifically, four parts, as the system of government envisioned by Diocletian was a Tetrarchy, a “rule by four.” The East and the West were the two principal divisions of the empire, each ruled by an Augustus. Each division was then subdivided into two additional regions, one under the control of the senior Augusti, the other under the jurisdiction of a junior emperor called a Caesar. In theory, each Caesar would “move up” and replace each Augusti as they died or retired. The new Augusti would then appoint new Caesars.

The division of the empire in the time of Diocletian can be seen below:

The purpose of the Tetrarchy was two-fold: to provide the empire with a stable plan of imperial succession that had been wracked by civil war for fifty years, and to make government of the sprawling empire more manageable by breaking it up into smaller administrative chunks.

The Tetrarchy was ultimately a failure, and by 325 the first Christian Emperor Constantine had again centralized all power under a single head, governing from the new capital of Constantinople. While the succession problem was temporarily solved by the advent of the Constantinian dynasty, the administrative burdens remained, and the Constantinian rulers frequently elevated other junior members of their house to de facto co-emperors, even if the empire was not technically divided. The Emperor Theodosius (379-392) was the last emperor to preside over at least a nominally united empire; after his death, the Roman Empire was again split between East and West, power going to the two sons of Theodosius.

The 5th century was a time of crisis for both halves of the empire, as barbarian incursions and military insurrections stressed the empire on all fronts. But while the Eastern Empire was ultimately able to ride out these challenges and survive for another thousand years, the Western Empire was not. With a lower population density, less material wealth, and less defensible borders, the Western Empire fell prey to the barbarian hordes. The last western emperors came to rely too heavily on barbarian foederati (barbarian army units) for military aid; by the 450s the most important men in the Western Empire were themselves of barbarian or half-barbarian blood.

In 476, a band of mixed barbarian foederati and mercenaries, led by the military leader Odoacer, captured the western capital of Ravenna and compelled the last western emperor, Romulus Augustulus, to abdicate the imperial office. Rather than declaring himself emperor in his place, Odoacer sent the imperial insignia to the Eastern Roman Emperor at Constantinople and told them that Italy no longer needed an emperor. Odoacer took the title King of Italy—a title confirmed by the Roman Senate. He ruled nominally on behalf of the eastern Emperor Zeno but in reality was an independent monarch.

Thus, while 476 does not necessarily mark the fall of the Roman Empire (it had practically collapsed in the west decades before), it does represent the extinction of the imperial title in the West. In the East, the empire continued on as it always had, although eventually losing its connection to the West as well as its veneer of Latinization. By the late 6th century it had assumed all of the foundational characteristics of the medieval Byzantine Empire, which it was rapidly transforming into. Its monarchs, ruling from Constantinople and speaking Greek, were no longer known as imperator but as basileus, the Greek word for emperor.

The Barbarian Kingdoms

Since the imperial title was allowed to go extinct in the west, hegemony passed to the new barbarian kingdoms. Italy was torn between the Arian Ostrogothic Kingdom (493-553) in the north, regions nominally under Byzantine suzerainty in the south, and then a fairly large chunk of land in central Italy that was more or less under the jurisdiction of the pope, although even here the Byzantine emperors claimed a very nominal authority—as late as the reign of Phocas (d. 610), the Byzantine Emperors still had their legislation posted in the Roman Forum as a claim to continued jurisdiction in the west.

In Hispania, the old Roman government had given way to the Kingdom of the Visigoths. The Visigoths had initially converted to Arianism, but in 587 their King Reccared I had converted to Catholicism under the influence of the famous bishops Leander and St. Isidore. The church in Visigothic Spain was vigorous; the canons of the many councils of Toledo on diverse matters of clerical discipline and doctrinal orthodoxy are among the toughest in the west. It is unfortunate that the secular rulers of Visigothic Spain were unable to mimic the energetic organization of their ecclesiastical counterparts, for the political situation in Spain under the Catholic Visigoths was always in disarray due to the constant internecine struggles of the nobility. This would lead to the fall of Visigothic Spain to the Muslims in 711, save for the tiny Kingdom of Asturias in the far north.

England had been Christianized during the first few centuries of the Christian era, but following the chaotic Anglo-Saxon invasions of the 5th century it had reverted back to a state of paganism under their Anglo-Saxon masters. Pope St. Gregory the Great sent St. Augustine of Canterbury to establish Christianity among the pagan Anglo-Saxons in 597, and the baptism of King Ethelbert of Kent followed soon after. The English, even as they accepted the faith throughout the 7th century, remained politically divided, their domain divided up into seven kingdoms called the Heptarchy. Thus, though Christianity flourished in the fertile soil of England, the affairs of that realm were for a long time of little importance outside the island of Britain.

Germany at the time was a hodge-podge of petty barbarian kingdoms, some Christian, some pagan. The Burgundians in what is now southern France, Switzerland, and west Austria were probably the most Christianized and civilized of these realms, but the Thuringians, Saxons, and Lombards also had potent kingdoms. Further east were the loose confederations of the Slavs, Gepides, Alans, Avars and other pagan nomadic tribes. Many missionaries labored among these peoples, both Greeks like Sts. Cyril and Methodius as well as westerners such as St. Boniface and St. Willibrord.

France was under the burgeoning Kingdom of the Franks, who had converted to Christianity beginning in 497 with the famous conversion of King Clovis, founder of the Merovingian house. The Frankish church boasted some of the greatest intellectual luminaries of the early medieval church, but like the Visigoths, the Merovingian government left much to be desired. The Merovingian kings waned in power until the most powerful men in the realm were not the kings but the Mayor of the Palace (maior palatii), and manager of the royal household, akin to a chief steward. As the Merovingian kings weakened this office became more important, as well as the family that held the office by hereditary right, the Carolingians.

By the 8th century the Carolingians were the power behind the throne. When the Muslims who had overrun Spain invaded France, it was to the Carolingian Mayor of the Palace, Charles Martel, that the Franks looked. Martel won a smashing victory over the Moors in 732 at the famous Battle of Tours. This epic battle not only broke the strength of the Muslim conquests, but it established the Franks as the most powerful barbarian kingdom in the west, and Martel as the single most powerful man in Latin Christendom. The Franks would be powerful allies of the papacy.

The Papal Dilemma

While the pope had exercised some temporal jurisdiction over central Italy since the mid-5th century, in practice central Italy was governed by the Church. This was always a hazardous proposition. The Church was an effective administrator, but it had very little by way of military power. If threatened, the popes had little recourse other than to hope another political entity stepped in to help. Until the 8th century, this tended to be the Byzantine Emperor. The largest occasion of eastern intervention was Emperor Justinian’s (527-565) twenty-year war in Italy to break the power of the Arian Ostrogoths, who were persecuting the Church. There were various other military incursions into the west, usually small and ineffective, for the Byzantines were wary of getting bogged down in military quagmires in the west. Sometimes they were totally inactive if there was no compelling political advantage to involvement; during the pontificate of Gregory the Great (590-604), the Lombards were making major military advances in northern Italy. The Byzantine exarch at Ravenna chose to do nothing and allowed the Lombards total freedom of movement, compelling Pope Gregory to take matters into his own hands and negotiate a separate peace with the Lombards (592). And after Gregory solved the problem, the exarch was enraged that the pope had taken this initiative.

This was compounded by the fact that when the Byzantines did choose to intervene, they often tried to exact concessions from the popes regarding the political and supposed ecclesiastical primacy of Constantinople in exchange. This dated back to the time of the Council of Constantinople (387) but especially since the time of John the Faster, Patriarch of Constantinople, who was the first to assume the title “Ecumenical Patriarch”; Pope Pelagius II would annul his acts. During the 8th century, the iconoclast emperors Leo the Isaurian and Constantine Copronymous tried to compel the pope to enforce their iconoclast edicts in the west, but to no avail. Indeed, the Iconoclast heresy had been a source of constant friction between the pope and the Byzantine Emperor.

By the mid-700s, the papacy was fairly exasperated by their dealings with Constantinople. Iconoclasm had come to an end with the reign of the Byzantine Empress Irene (r. 775-803), but relations with the Byzantines remained poor as the popes were caught in the middle of a war between the Franks and the Byzantines over the territories of Benevento in southern Italy and Istria on the east coast of the Adriatic.

Thus the popes were in a very difficult spot. Traditionally trying to maintain their traditional ties to the Byzantine court at Constantinople was marred by recurrent heresy, Byzantine inactivity, political pressure, and a growing cultural divide between the Latin west and the Greek east. But if the pope abandoned Rome’s ties with Constantinople, where could the pope turn in times of crisis when military aid was necessary?

The Coronation of Charlemagne

Charlemagne (Charles the Great) was the grandson of Charles Martel, the savior of Europe. After Martel’s victory at Tours in 732, the stature of the Carolingian family was so great that Martel’s son, Pepin, was able to peacefully overthrow the last Merovingian king and assume the kingship of the Franks in 751. Pepin’s son Charlemagne came to the throne in 768.

The Carolingian family had already had a history of strong ties to the papacy. In 754, King Pepin brought his Frankish armies into Italy to drive out the Lombards, who had demanded tribute from the pope. Pepin was successful, and confirmed that the lands of central Italy should be under the exclusive temporal rule of the Bishop of Rome. This established the legal framework for the future “Papal States” and gave the other barbarian kingdoms a warning that central Italy was off-limits – and that any violence against the Church’s holdings there would be answered by the Franks. The so-called “Donation of Pepin” established the independence of the Church from the meddling of the Lombards, but it also secured central Italy’s unquestionable autonomy from Byzantium and won the Carolingians the good will of the popes. The pope would soon need to put this good will to the test.

In 799, a Roman mob stirred up by opponents of the reigning pontiff – Leo III – endeavored to kidnap the pope with the intention of gouging his eyes out and pulling out his tongue. This was not mere malice; the intention was to render the pope physically incapable of holding his office and thus necessitating a resignation and new papal election. Pope Leo fled from Rome and went north to Spoleto, where he was told that Charlemagne was holding court at the German city of Paderborn. Leo presented himself to Charlemagne, who was indignant at the pope’s adversaries. On December 23, 800, Pope Leo III swore an oath of innocence to all the accusations against him and was escorted back to Rome by Charlemagne and his army.

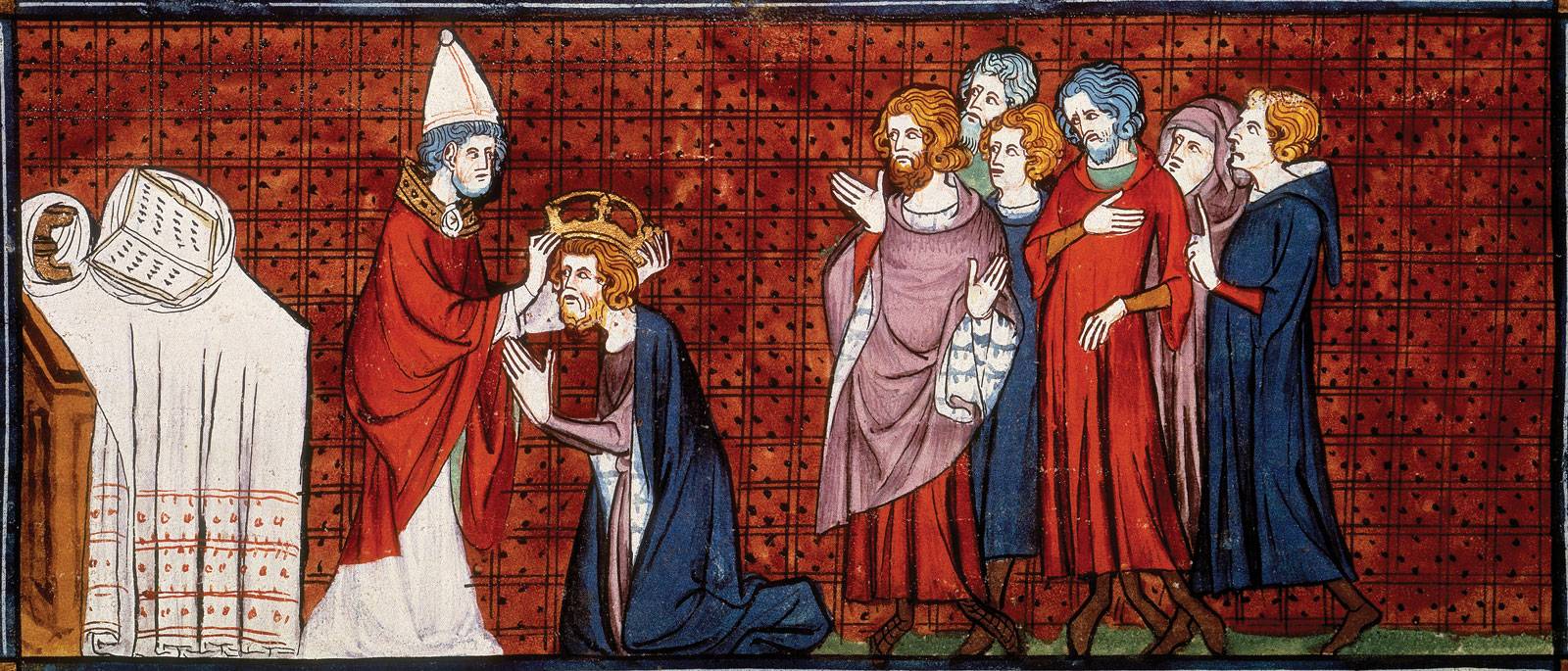

Since he was in Rome, Charlemagne took the opportunity of hearing Christmas Mass in St. Peter’s basilica. As he was praying at the altar, Pope Leo approached Charlemagne with a crown and placed it upon his head, declaring him to be Imperator Romanorum (“Emperor of the Romans”). Charlemagne later claimed that he had no idea that the pope intended to crown him, and that had he known he would not had set foot in the basilica that day; other historians, skeptical of this story, note that Charlemagne could not have failed to notice the large crown sitting beside the altar.

The Translatio Imperii

The motives and foreknowledge of Charlemagne are known to God alone. The coronation was of pivotal importance in the history of Christendom and Europe—probably the most monumental event to happen on Christmas since the birth of Christ. How did the imperial coronation of Charlemagne affect the subsequent development of Europe?

When Charlemagne was crowned Roman emperor by the Pope in the year 800, his kingship took on a much more sacral identity than any previous European kingship in the Latin west. The coronation of Charlemagne as Roman emperor was seen by contemporaries as falling directly in line with the imperial tradition of ancient Rome; thus, Charlemagne is crowned as “Imperator and Augustus,” as his biographer Einhard tells us. This is the beginning of the medieval notion of the translatio imperii, the idea that the imperial authority, the highest secular power in Christendom, had been “transferred” from the Byzantines to the Germans by the Pope.

This concept of translatio imperii is of supreme importance. In bestowing the imperial title upon Charlemagne, the pope was not claiming to resurrect the imperial office of the west, extinct since 476. Rather, he was “translating” or “transferring” the imperial title from Constantinople. The Byzantine Empress Irene was considered a usurper because there had been no custom in the Roman Empire—legal or otherwise—of a woman wielding imperial authority. Irene had succeeded her son Constantine VI to the Byzantine throne, a succession neither the pope nor the Franks regarded as valid. In giving the imperial authority to Charlemagne, the pope was proclaiming Charlemagne the successor not of Romulus Augustulus, but of Constantine VI. The imperial authority, though divided in the late empire, was ultimately one. The pope, as Vicar of Christ, claimed the authority to be able to “translate” this one authority back to the west when the line of succession died in the east. Charlemagne became the imperial authority in Latin Christendom.

The Byzantines obviously disagreed with the pope’s theory, and the subtleties of it were probably lost on Charlemagne. Even so, the bestowal of divine imperium from the hands of the Pope gave him new incentive to portray his power as sanctioned by God. Thus began what may have been the Middle Ages’ most intensive and effective propaganda campaign, with the goal of establishing the Carolingians as the God-ordained rulers of the new Roman Empire. Charlemagne carried out this project by assembling at his court a vast array of scholars and intellectuals from around Europe, partly to consolidate and legitimize the authority he claimed, partly out of a genuine love of learning and scholarship.

This had profound ramifications for both Church and the Frankish kingdom. It had benefits and drawbacks. On the one hand, the papacy finally had a defender upon which it could depend. The Frankish dominions extended right into Italy, and as long as it endured the Carolingian Empire was faithful to the arrangement of Charlemagne. This ultimately meant that Italy and the papacy became west-ward looking; instead of turning to the east and the court of Byzantium, they pivoted west, casting their lot in the French. It is because of this that Italy is considered part of western Europe and not the east. It also granted a kind of divine sanction and aura of sanctity on Charlemagne.

Charlemagne’s legacy in France and all of Europe was immense; all future Christian kings would look back on him in some way or another as an exemplar. Charles the law-giver, Charles the protector of local rights and charters, Charles as an ancestor of the Hapsburgs, and Charles even as a saint: these conceptions show how much of the destiny of the German people turned upon his influence and achievements. Even the map of Europe as we know it today goes back to the divisions of the Carolingian kingdom stemming from the Treaty of Verdun in 842.

But on the other hand, the imperial coronation of Charlemagne meant that the imperial authority in the west would always be, in some way, beholden to the pope. In the 10th century, when the imperial authority passed to the house of Otto the Great and the Germans, no emperor could claim the imperial title until it was conferred by the pope – and if the pope disapproved of his actions, the emperor-elect might have his imperial coronation held up for years, as was the case with Frederick II, who became king in 1196 but was not crowned emperor until 1220, a full twenty-four years later. Thus the imperial coronation became a kind of political tool in the strife between papacy and empire that characterized the high Middle Ages.

The popes, too, experienced negative ramifications from the arrangement inaugurated on Christmas Day in the year 800. By wedding themselves to the Carolingians and the western imperial authority, the popes implicitly acknowledged a special right of those rulers to meddle in the affairs of the Church by virtue of their special guardianship over the pope. Emperor Otto I (d. 973) would exploit this right by taking advantage of a chaotic period in the papal government to claim the right of choosing the pope, the so-called “Ottonian Privilege.” This state of affairs led directly to the Investiture Controversy, the nearly fifty-year conflict between the pope and the Holy Roman Emperors over whether bishops could be invested with the signs of their ecclesiastical office by secular lords. Though the Church emerged victorious, this imperial-ecclesiastical conflict was incredibly destructive and sowed the seeds of secular antipathy to the papacy that would rear up in the 14th century.

Conclusion

But that was all still a long way off on that happy Christmas Day in the year 800. The imperial coronation of Charlemagne by Pope Leo III secured his place as the greatest of all Christian monarchs and gave his rule the popular support he needed to extend Carolingian dominions across Europe, thus carving out the boundaries of the European kingdoms as we know them. All students of Catholic or just European history should have Christmas Day of the year 800 anchored in their minds as one of the most important moments in Christendom.

If you’d like to learn more about this subject or the issue of Church-State relations in the Middle Ages in general, please see Phillip Campbell’s book Power from On High: Theocratic Kingship from Constantine to the Reformation (Cruachan Hill Press, 2021).

Phillip Campbell, “The Coronation of Charlemagne,” Unam Sanctam Catholicam, December 22, 2015. Available online at http://unamsanctamcatholicam.com/2022/06/coronation-of-charlemagne