Every time there is a papal conclave you can be sure the internet will be flooded with articles on the prophecies of St. Malachy, the 12th century Irish bishop who allegedly prophesied the succession of popes untilt he end of time. These article usually from mainstream Catholics commentators who are bent on convincing people that the prophecies are forgeries that serious Catholics need give to credence to. The authors usually state that they are writing for the purpose of addressing the St. Malachy/Petrus Romanus “hysteria” that has attended papal interregnums as of late—although ironically most of the hysteria about the prophecies seems to be from those bent on debunking them.

As two examples of the sorts of articles I am talking about, take this article by Dr. Donald Prudlo published on the Truth and Charity Forum at Human Life International, which basically denigrates the prophecies as “papal campaign literature from the 1590’s” and says they are “vague utterances that a local horoscope page would be embarrassed to print.” Or we could take this one by Gerald Korson from Catholic Online, who feels the need to “debunk” the prophecy and says they are “about as reliable as the Mayan calendar.” These are some of the most recent examples, but there have been many others as well.

There is nothing wrong with engaging in argumentation about the credibility or incredibility of private apparitions or prophecies about which we are permitted to disagree. We should, however, tread lightly here, as these prophecies of Malachy were prognostications attributed to a canonized saint that have been believed by many scholars and even popes for at least four centuries; they should not be summarily dismissed with such a cavalier attitude.

Malachy’s prophecies have always been questions, but the approach was traditionally one of respectful and reserved skepticism. For example, the 1913 Catholic Encyclopedia mentions the arguments against the authenticity of the prophecy, but it also points out that none of these arguments are conclusive and that the jury is still out. Historically, the prophecy has always been approached in this “jury is still out” manner. However, now that we are up to the end of the sequence (the pontificate of “Peter the Roman”) the attitude has changed to one of outright hostility and ridicule by people who are horrified any time any Catholic starts thinking seriously about eschatological fulfillments—as if the worst possible thing a Catholic could do would be to think we could be on the verge of a divine chastisement. But like it or not, the Malachy prophecies have a very long pedigree in the western Church, and we should not be so quick to mock them or speak derisively about them.

Are there arguments against the prophecy of Malachy? Absolutely there are, and they are strong; but there are also arguments in favor of its authenticity. Regardless which position we take, neither is conclusive, and the strongest arguments against their authenticity are ultimately based on mere speculation, as we shall see. Therefore, since St. Malachy was in fact a canonized saint, and remembering St. Paul’s admonition “Do not despise prophecy”, (1 Thess. 5:20), let us take a more objective look at the case of St. Malachy’s prophecy.

The Authenticity of the Prophecies of St. Malachy

When discussing whether the prophecies of St. Malachy are authentic, what do we mean by these words authentic and authenticity? There are two ways in which we can speak of “authenticity” relating to these prophecies:

(1) Whether or not the prophecies were in fact uttered by Malachy or at least date to the 12th century. If they can be traced back to Malachy or his era, they are considered “authentic.”

(2) Whether or not the prophecies are divinely inspired and can be expected to be fulfilled. If they are divine and can be expected to be fulfilled, they are “authentic.”

Of course, we have no way of conclusively proving the second meaning of authenticity one way or another; no Catholic can have absolute certainty about any private revelation, and the timeframe of Malachy’s prophecy has not yet run its course. This discussion will be therefore be confined to considering the first definition of authenticity: whether or not the prophecies are actually from the 12th century as they purport to be, or whether they are in fact 16th century forgeries.

St. Malachy the Prophet

Let us remember, first off, that St. Malachy (d. 1148), was a legitimate prophet. The Breviary entry for his feast day notes that he was gifted with prophecy, and St. Malachy is also remembered for a very famous prophecy that Ireland would be oppressed by England for seven centuries, at the end of which time England would suffer a chastisement and Ireland would help restore the Faith to England. Much of this prophecy has come true and has been authenticated, a manuscript of it having been found at Clairvaux dating from the time of Malachy. Thus, if Church tradition records he was a prophet, and if he made other accurate prophecies of events centuries to come, why is it implausible that the prophecy of the popes is not similarly authentic?

The Simoncelli Hypothesis: Origins and Problems

The writings of those bent on disproving the prophecies the Malachy tend to object that the prophecies are probably spurious because the text of the prophecies do not show up until around 1595, over 450 years after their alleged authorship in 1143. In the two articles cited above, Mr. Korson and Dr. Prudlo both state that the late discovery of the text authorship is enough to throw them out as a forgery. Dr. Prudlo considers this to be the strongest argument against them and states that this fact alone is “enough to discount the story even before considering the internal evidence.” So, without even considering the content of the prophecy, the fact that they do not enter the historical record until 450 years after their alleged authorship rules out their legitimacy entirely. Prudlo and Korson both use different dates; Dr. Prudlo says they are not mentioned until 1590; Korson says 1595.

These dates are based on the assumption that the prophecies were actually written by the party of one Cardinal Girolamo Simoncelli, a cardinal-elector in the conclaves of 1555, 1559, 1566, the two in 1590, 1591 and 1592. The theory is that the prophecies were written to bolster the candidacy of Cardinal Simoncelli (who was a strong papabile in the conclaves of 1590-92) by depicting Simoncelli as a pope prophesied from centuries back.

Korson, Dr. Prudlo and other detractors of the prophesy take the Simoncelli thesis for granted and assume its truth. But where does the Simoncelli hypothesis come from? This theory can be traced back to Fr. Claude-Francois de Menestrier, S.J. (1631-1705), an antiquarian who published nine volumes on medieval heraldry and emblems. Menestrier was the first proponent of the Simoncelli hypothesis, which he formulated based on his opinion that the prophecies before 1590 are very specific while those after 1590 are disappointingly vague. He therefore cites the party of Simoncelli as the forgers and even names a specific forger, but regrettably does not furnish us with any evidence whatsoever in support of the opinion, leaving us to understand that his opinion is simply a theory. This is the ultimate origin of theory that the prophecies are a 1590 forgery.

Why 1590? According to Dr. Prudlo, the year 1590 refers to the first publication of the prophecies by Benedictine historian Arnold Wion. The 1595 date cited by Korson is the year Wion republished the prophecies in his book Lignum Vitae. Regarding Wion’s book, he was assisted in his translation of the prophecies from a medieval manuscript by the Spanish monk Alfonso Chacon, a renowned antiquary and scholar of medieval texts. To Chacon fell the important task of authenticating the manuscript and making sure it was not a forgery, and it is noteworthy that the manuscript did pass the scrutinizing eye of Chacon and was authenticated. It was Chacon who rendered many of the prophecies into the phrases we are familiar with today.

We should note, however, that the 1590 date assigned by Menestrier is misleading, which is unfortunate since this is the date that has been subsequently repeated by commentators. The prophecies were not discovered in 1590, but in 1556 by Augustinian historian and antiquary Onofrio Panvinio, who apparently published the first edition of the prophecies in Rome around 1557. Wion’s inclusion of them in the Lignum Vitae was more well known, but came thirty-three years after the publication by Panvinio. We shall say more on Panvinio later, but it is sufficient here to note that the true discovery of the text in 1556 is seriously problematic to the theory that the prophecies were created by Cardinal Simoncelli, who was only thirty-three at the time, had only been a Cardinal for three years, and was not considered a papabile until almost three decades later. Fr. Menestrier did not deduce the prophecies as a forgery based on the 1590 date; rather, he started with the assumption the prophecies were false and then hypothesized the 1590 date to justify his theory about Cardinal Simoncelli. This is not sound methodology.

Another edition of the prophecies was published by Girolamo Muzio in 1570. Muzio, likewise, believed in their authenticity. Muzio’s 1570 edition of the prophecies was written in Italian and cumbersomely named Il Choro Pontifico Nel Qual Si Leggono Le Vite Del Beatissimo Papa Gregorio& Di XII Altri Santi Vescoui. Thus we have two editions of the prophecies in circulation prior to the 1590 date cited by Prudlo and the 1595 date preferred by Korson.

Even if we grant this, however, we merely exchange one problem for another; instead of a 450 year silence, we have a 413 year silence. Is the 413 year silence about the prophecies problematic? Yes. Is it damning? No. The question really is not whether or not the text was “missing” for 413 years, but whether or not there is a good explanation for it—and whether we accept it or not, there is in fact a traditional explanation for this lacuna. The French Abbe Cucherat, in an 1871 work on the prophecies, repeats an older tradition that the prophecies were in fact legitimate and were delivered by St. Malachy to Pope Innocent II in 1143 in order to comfort the Holy Father during a time of discouragement and illness, but that the pope subsequently filed the manuscript away at the Vatican where it remained lost until its discovery in the late 16th century. This would explain the 413 year absence of the manuscript from the historical record. Cucherat unfortunately gives no evidence for his hypothesis, so it remains as theoretical as that of Menestrier.

Even if Cucherat gives no evidence to back up his assertion, the simple fact that a text allegedly went missing for four centuries is not enough to discount the story prima facie, as Dr. Prudlo would have it. There are multiple well-known examples of texts getting lost at the Vatican for centuries. It is actually quite common. People tend to forget how voluminous the archives of the Vatican are, where documents have been amassing since the pontificate of Pope St. Damasus I in St. Jerome’s day (see the book Vatican Secret Archives by Terzo Natalini for an excellent history of papal record keeping). For example, the oldest extant copy of the Scriptures, the Codex Vaticanus, came to the Vatican sometime in the late 4th century and was lost for over a thousand years, rediscovered only in the early 15th century; if the disappearance of the obscure text of St. Malachy’s prophecy for four centuries is problematic, the disappearance of the Codex Vaticanus for a thousand years is immensely more so. The Dead Sea Scrolls and the Codex Sinaiticus share similar histories, each of which were lost for almost two thousand years. And, lest we doubt how easy it is to lose stuff in the Vatican, let us not forget that the tomb of St. Peter himself was lost in the Vatican until discovered during the reign of Pius XII (1953) and only positively identified as that of Peter by Paul VI in 1968. If the Church can even lose the tomb of St. Peter for two thousand years, then it is not at all unbelievable that the text of Malachy’s prophecy could be lost for 413. This of course does not prove its authenticity, but at the very least, it should allow us to admit that this problem does not amount to an ipso facto declaration of invalidity, as Dr. Prudlo would have.

Arguments from Authority

Another argument in favor of authenticity is that two of the greatest scholars and exegetes of the Tridentine period considered the prophecies completely authentic: Cornelius Lapide (1567-1637) and Onofrio Panvinio (1529-1568). As we have seen above, it was Panvinio who first discovered the manuscript in the Vatican archives and remained one of the firmest believers in the prophecies. Panvinio was no novice; the chief librarian and editor of the Vatican Library, he authored over 16 major works on history and archaeology and was considered the foremost authority in medieval and ancient Roman history. It is unfortunate that we know nothing of the manuscript that Panvinio worked from save that it was discovered in the Vatican, but Panvinio’s magnificent work and spotless reputation should preclude any assumptions of fraud on his part. So renowned was Panvinion that during his lifetime he was called pater omnis historiae (“father of all history”).

Cornelius Lapide (1567-1637) was a universally acclaimed student of scripture and prophecy whose works are still being translated and circulated today. Lapide studied the prophecies of Malachy extensively, believed in them, and wrote a tract attempting to establish a chronology to identify the approximate time we could hope to see Peter the Roman.

Other scholars who published, or commented, or otherwise supported the authenticity of the prophecies were Giovannini de Capugnano (d. 1604), Jean Boucher (1623), Chrisostomo Henriquez (1626), Thomas Messignham (1624), Angel Manrique (1659), Michel Gorgeu (1659), Claude Comier (1665), Giovanni Germano (1675), Louis Morerl (1673), John Toland (1718), the latter of whom wrote a treatise on the destruction of Rome during the pontificate of Petrus Romanus. We have already mentioned the Abbe Francois Cucherat (1871), who wrote extensively on the prophecies. It is worth mentioning that despite the assertion of Dr. Prudlo, who claims that the manuscript disappeared in the 16th century, Abbe Cucherat reports having seen the original manuscript in the Vatican in the 1860’s, though this is disputed.

All of these authorities were men of erudition, most of them scholars, historians, and antiquarians familiar with medieval heraldry and the procedures of humanist textual criticism. None of them had any doubt about the authenticity of the manuscript. Granted, arguments from authority are not the strongest, but when so many luminaries of Catholic scholarship spanning so many years wholeheartedly accepted the prophecies, we should at least do them the courtesy of not rejecting them out of hand.

Fr. Menestrier (d. 1705) was the first one to suggest the prophecies were a forgery. However, Menestrier apparently never knew of the study of Alfonso Chacon, the expert paleolographer who subjected the original manuscript to rigorous scrutiny in the 1590’s and proclaimed it authentic. Chacon’s entire profession consisted in sorting out fraudulent texts from the authentic, and he proclaimed Malachy legitimate. However, as stated above, Menestrier had no knowledge of this study, which should be taken into account when evaluating the merits of his skepticism.

Evidence of Malachy’s Prophecies before 1556

Even if we were to throw out the testimony of Lapide, Panvinio, and all the others, we might still make an argument for authenticity based on the bits and pieces of Malachy’s prophecy that seem to have been circulating around as far back as the 13th century. There is the interesting case of the thirteenth century De Vaticina Summis Pontificibus. De Vaticina Summis Pontificibus is a collection of two manuscripts of papal prophecies later joined into one. The first part was written around 1280 and contains fifteen papal prophesies beginning from the pontificate of Nicholas III (1277-1280); the second part was composed around 1330 and contains an additional fifteen prophecies. Around the time of the Council of Constance (1414), the manuscripts were combined into one for a total of thirty papal prophecies. The prophecies consist of very short Latin phrases using plays on words, puns, and allegories, as do the Malachy prophecies, and are strikingly similar in many respects. In the 14th and 15th centuries, these prophecies were even more well-known than the prophecies of St. Malachy would be in the 16th and 17th. It could of course be reasoned that Malachy was inspired by this earlier work, but it could just as easily be asserted that the vignettes of De Vaticina Summis Pontificibus represented hastily copied portions of Malachy that were circulating around and thus provide evidence that the prophecies of Malachy did in fact exist prior to 1556.

It is also interesting that, even before the appearance of the texts published by Panvinio and Wion, badges or medals with enigmatic engravings were circulated during papal conclaves, at least going back to the high Renaissance in the 1400s. These badges were used to influence several conclaves, and these medallions are described briefly in the work of the French author Roger Duguet in his book Around the Tiara (1997). Thus, even if the text of St. Malachy was not published until 1590, the people living at Rome in the previous century were familiar with these sorts of papal “prophecies”, which again could be evidence of the circulation of earlier fragments of Malachy.

Are Malachy’s Prophecies Too Vague?

The reason Fr. Menestrier originally settled on 1590 as the date for the prophecies creation was because he opined that the prophecies before 1590 were incredibly accurate while those after 1590 were disappointingly vague. This criticism has been repeated ever since, and appears in both of the current articles of Korson and Dr. Prudlo.

A reading of the actual text, however, does not bear this out. Some of the pre-1590 prophecies certainly are specific; for example, Concionator Gallus (“French Preacher”), referring to Pope Innocent V (1276), who was both a Frenchman and a member of the Dominicans, the Order of Preachers; likewise, many post-1590 prophecies are vague, for example, Rastrum in Porta (” The Rake of the Door”) referring to Innocent XII (1691-1700), of whom no interpreter has found a satisfactory link to the title in Malachy.

But this tendency is not at universal, as many of the pre-1590 prophecies are just as vague as the post-1590 collection. In addition to this, many of the post-1590 prophecies are remarkably accurate. To give an example in the first case, Ex Ansere Custode (“From the Guardian Goose”), applying to Pope Alexander III (1159-1181), which is horrendously vague and can only be connected to Alexander III by the tortuous argument that the Pope must have been descended from the patricians who saved the Capitoline citadel from Brennus and the Gauls in 390 BC when a flock of geese sacred to Juno warned the Roman guards of a secret attack. This convoluted interpretation was put forward by Cucherat in 1871 and is the only attempted explanation to date. So clearly not all of the pre-1590 prophecies are recorded with “relative accuracy” (Korson) or are even close to “spot-on accurate” (Prudlo).

Conversely, many of the post-1590 prophecies are strikingly appropriate. This is even noted by the 1913 Catholic Encyclopedia, a text not at all given to superstition or unwarranted credulity. It states:

Those who have lived and followed the course of events in an intelligent manner during the pontificates of Pius IX, Leo XIII, and Pius X cannot fail to be impressed with the titles given to each by the prophecies of St. Malachy and their wonderful appropriateness: Crux de Cruce (Cross from a Cross) Pius IX; Lumen in caelo (Light in the Sky) Leo XIII; Ignis ardens (Burning Fire) Pius X. There is something more than coincidence in the designations given to these three popes so many hundred years before their time. We need not have recourse either to the family names, armorial bearings or cardinalatial titles, to see the fitness of their designations as given in the prophecies. The afflictions and crosses of Pius IX were more than fell to the lot of his predecessors; and the more aggravating of these crosses were brought on by the House of Savoy whose emblem was a cross. Leo XIII was a veritable luminary of the papacy. The present pope is truly a burning fire of zeal for the restoration of all things to Christ. (source)

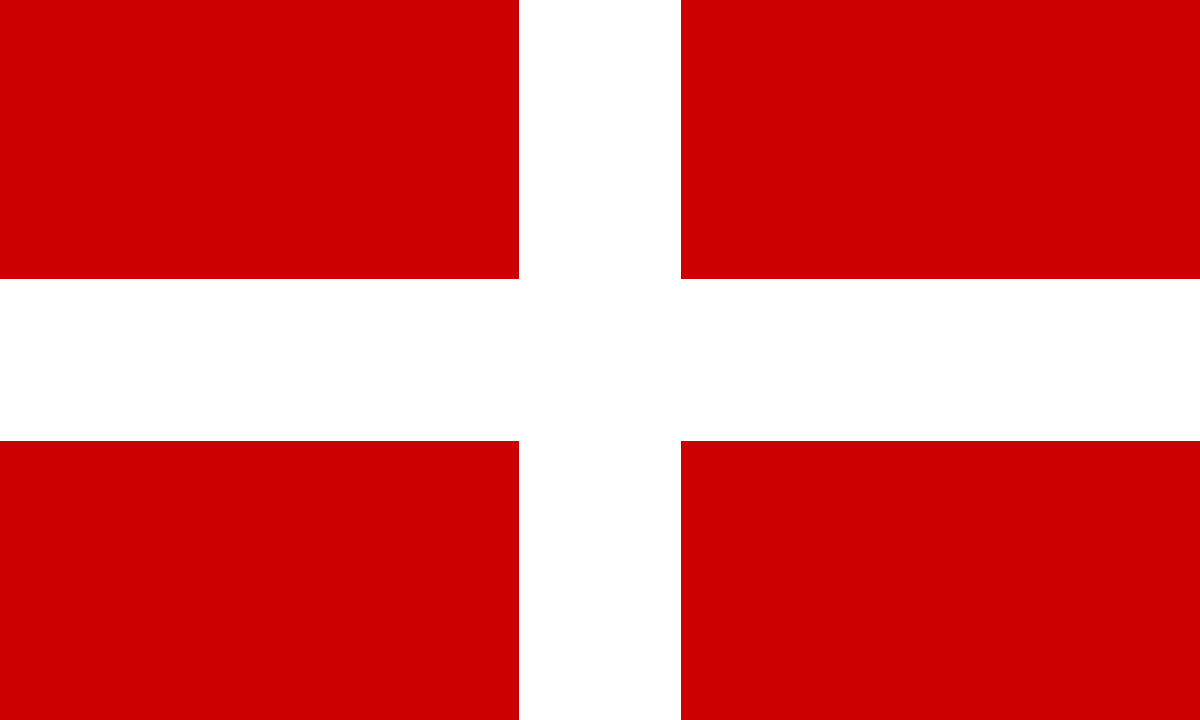

The case of Pius IX is particularly striking: Cross from a Cross. In losing the papal states and facing the atheist risorgimento, he suffered greater crosses than any other pope of the modern period. Furthermore, these sufferings were brought about by the attempts of the House of Savoy to unify Italy; the emblem of the House of Savoy was a large white cross emblazoned on a red shield. Thus the title “Cross from a Cross” for Pius IX is beautifully appropriate. Equally accurate is Aquila Rapax, “A Rapacious Eagle”, applied to Pius VII (1800-1823), who was actually kidnapped by Napoleon Bonaparte, one of the most rapacious conquerors in all of history, whose emblem was an eagle. The title for Benedict XV (1914-1922) is also amazingly accurate: Religio Depoulata (“Religion Laid Waste”); the pontificate of Benedict XV was overshadowed by the deaths of millions of Christians in World War I, the slaughter of millions more in the Turkish genocide, the outbreak of the Communist revolution in Russia that would lead to millions more dead and the spread of atheism around the world. This prophetic title was fulfilled to the very letter.

Clearly there is not the strict pre/post-1590 division in the quality of the prophecies that Menestrier imagined—remember, Menestrier died in 1705 and thus never witnessed the spectacular events of the above mentioned modern pontificates and their marvelous correlation with the titles found in Malachy.

Are the prophecies less precise than we would like? Granted; most of them are two or three words at most. But are the explanations and correlations always as torturous as critics state? Not at all, as we have seen. Let us also remember that vagueness is not necessarily an argument against the authenticity of a prophecy. Many legitimate prophecies from Sacred Scripture are extremely vague. Let anyone to go back and read Hosea 11:1 (“out of Egypt I called my son”) in context and see how one could possibly deduce the Flight into Egypt from it before the fact. Likewise, can anyone honestly say that the election of Matthias to replace Judas in Acts 1 is clearly and evidently found in Psalm 109:8 (“May his days be few, and may another his office take”)? Not likely. Yet Divine Revelation tells us they are authentic prophecies nonetheless. These biblical prophecies are vague, even vaguer than the ones found in St. Malachy. It often happens that vagueness is a trait of genuine prophecy; in fact, extreme specificity is often times a sign that a prophecy is false.

The Inclusion of Antipopes

One problem often brought up with the Malachy prophecies is their inclusion of several anti-popes. Korson sees this as a strong indictment against the legitimacy of the prophecies. He says, “[The] list in itself is erroneous; in several instances, it leaves out legitimate popes in favor of anti-popes, those false claimants to the papacy who surfaced at various troubled moments in the history of the Church.”

Here we have a case of wanting to have our cake and eat it, too. Remember, if we are asserting that the prophecies were not written in 1143 but sometime around 1590, then we are presuming that the author had the benefit of retrospect; that is, though there frequently were anti-popes during the period of the Western Schism, by 1590 that would have all been resolved, and we could presume our forger in 1590 to have a single, accurate list of legitimate popes at his disposal. The fact that the Malachy prophecy contains anti-popes is actually a point in favor of legitimacy, not against it. Malachy scholar Peter Bander puts it this way:

“I consider those objections quite unreasonable…These antipopes are historical characters, they all held high episcopal offices before claiming the supreme title to the See of St. Peter and, they were, within limits, accepted as real popes by a large section of Catholic followers; the fact that events proved them wrong or even schismatic does not belittle the important function and position they commanded at the time. Giacconius, who in his commentary on Malachy’s prophecy lists only canonically elected popes, quarrels with Panvinio for ranking popes and antipopes next to one another. This great schism in the Catholic Church, when popes and antipopes existed side by side, lasted for almost three centuries [reckoned from the time of Celestine II, within Malachy’s life, to Felix V, 1449]. St. Antoninus himself comments on this and points out that much is written by different parties in defense of the one or the other ecclesiastical dignitary. All sides were well defended by excellent theologians and canon lawyers, and in the end, the argument was settled by establishing the rightful successor of St. Peter as the one who was canonically elected to the office. St. Antoninus goes further by saying that ordinary people could not possibly partake in such difficult and delicate discussions as they did not understand canon law; they followed the advice of their spiritual fathers and superiors. Personally, I consider the fact that antipopes are included in the list as a point in favor of Malachy” (The Prophecies of St. Malachy, edited by Peter Bander, Tan Books, 1973, pg. 14).

Since the line of succession had been clarified by 1590, we should assume that had the prophecies been forged, there would be no incentive to include anti-popes in the list. However, if at the time of authorship these anti-popes were still to come, it makes perfect sense that their names would have appeared in the prophecy as at least putative holders of the See of Rome. To put it another way: A Englishman in 2023 reciting a list of the kings and queens of his kingdom would not include in the list usurpers such as Lady Jane Grey (d. 1554) and Edgar the Aetheling (d. 1126); they would only recite the officially established succession that had been settled by law over the the course of the centuries, omitting those who aspired, but never managed to retain, the throne. It would make sense that a list written in 2023 would omit these disputed claimants. However, suppose an Englishman living back in 1066 had a vision of all the men and women to sit on the throne of England until the end of time. In his case, it would make perfect sense that usurpers like Jane and disputants like Edgar would appear in the vision, since both claimed the royal authority and were acclaimed as monarch by large segments of the population for a time. Furthermore, if the vision was for a time yet to come, it makes sense that the recipient might not know whether one in the vision was a true monarch or not. Similarly, the presence of anti-popes in the list of St. Malachy is an argument in favor of a 12th century composition, not against it.

But, just to be clear, many of the anti-popes in Malachy are in fact specifically called out as anti-popes, such as Corvus Schimaticus and Schisma Barchinonicum (Nicholas V and Clement VIII), so it is not as if the anti-popes are ranked exactly side by side with legitimate popes, as the historian Giacconius opined.

Incorporation by the Popes

Finally, we come to what may be the most overlooked and strongest pieces of evidence in favor of the authenticity of the prophecies of St. Malachy: the indisputable fact that for hundreds of years the popes themselves have taken the prophecy seriously and have gone out of the way to make sure they fulfilled it.

Carlo Marcora, an Italian historian who did an exhaustive six volume study on the papacy published from 1961 to 1974, noted that many of St. Malachy’s titles were applied to specific pontificates with papal approval. Thus Pius VI allowed himself to be referred to as the Peregrinus Apostolicus, Lumen in Caelo was applied to Leo XIII, and Pastor Angelicus to Pius XII; Pastor Angelicus was even the name of the officially sanctioned 1942 biographical documentary of the life of Pius XII and book published posthumously in 1958. If Pius VI, Leo XIII or Pius XII thought the prophecies of Malachy were forgeries, allowing themselves to be publicly identified with them throughout their pontificates was a strange was to show it.

Popes have also intentionally tried to show that a particular prophecy was fulfilled in them. Take Clement XI (1700-1721), who in Malachi’s prophecy is Flores Circumdati (“Surrounded by Flowers”). When no one of the new pope’s party could figure out how to connect the phrase with Clement, the pope had a coin struck which bore the motto Flores Circumdati on it. The pope and his circle were clearly trying to show the prophecy was fulfilled, which means they took it seriously. There are many anecdotal tales of popes consulting the prophesy upon their election and choosing their papal coat of arms accordingly in an attempt to fulfill it. Consider that since 1590, popes Urban VIII, Paul V, Alexander VII, Clement IX, Gregory XVI, and Leo XIII all apparently incorporated elements of Malachy’s prophecies directly into their coat of arms; many more if you include pre-1590 popes.

It can be objected that this sort of thing is self-fulfilling prophecy, but the point is irrelevant. We are not here seeking to prove that the prophecies are true, but that the successive popes have believed or acted as if they were true, which they clearly have right down to our own day. Even Joseph Ratzinger, clearly not ignorant that he was supposed to be Gloria Olivae and knowing the speculation connecting the name with the Benedictines, obliging chose the papal name Benedict. The popes have clearly taken this prophecy seriously over the years and incorporated it into the emblems and symbolism of the papal office. Does this give the prophecy some sort of papal sanction? No. But it should give us pause—modern Catholic pundits blast the prophecies as fraudulent while for centuries pope after pope has given credence to them by going out of their way to make sure they are fulfilled. If the Vicars of Christ on earth take St. Malachy seriously, how do we fare when we recklessly toss them aside and speak so derisively about them?

Conclusion

We have reviewed numerous arguments in favor of the historical authenticity of Malachy’s prophecies. But are they true? Do they accurately portray the succession of popes till the Second Coming? The jury is still out, which remains the best approach to this question. But clearly the evidence presented above should rule out any sort of automatic dismissal of the prophecies. Many erudite scholars have spent a long time studying these prophecies and have given them credence. Many of the prophecies have been eerily fulfilled in very literal ways, and the popes themselves have given a nod to them. The prevailing hypothesis that they were forged by someone in the pay of Cardinal Simoncelli at the 1590 conclave is manifestly false, as the manuscript was discovered 34 years before the conclave of 1590—and there is good evidence to suggest that parts of the prophecy were known as early as 1280. While the scholars who fully believed in the authenticity of Malachy were legion, the dismissal of the text as a fraud can be traced to a single Jesuit scholar (Fr. Menestrier) who did not have all the facts at his disposal.

This is not to argue that the prophecies of St. Malachy are inpsired by God, but the case is by no means closed on them. Fortunately, we are at a point in history where we will not need to wait too long to find out.

Phillip Campbell, “Prophecies of Malachy: Case for Authenticity,” Unam Sanctam Catholicam, Feb. 1, 2013. Available online at https://unamsanctamcatholicam.com/2023/04/prophecies-of-malachy-case-for-authenticity