So long as you have not been living in a cave for the past thirty-years, you have most likely noticed some of the bizarre fads in hair and clothing that have come and gone. How about loose pants sagging down below the buttocks? Or the Goth look of wearing pounds of metal chains dangling off of everything? Or what about the unfortunate “skinny-jeans” fad of recent years? Or the long, claw-like artificial nails preferred by young women today? Or the unanticipated resurgence of the mullet among young men?

As long as we are in the world, we will always deal with goofy fads in clothing and hairstyles. When I was young it was ponytails and tons of hairspray with bright neon colored clothing; later it was mohawks and grunge flannels. In my father’s day it was all the nonsense associated with the Hippie movement and the fashion-blight that was the 1970’s. As long as human beings exist in this world, each generation will have its own things that it considers fashionable. And each fad and fashion will, to a certain degree, provoke a backlash against it by those who consider it improper or simply ridiculous.

While much about fashion is subjective, there is a strong core of objective guidelines relating to what is and is not acceptable fashion for a Christian. No matter what age we look in, we can always find exhortations from the saints to dress in a manner that is not too showy, modest, appropriate for one’s state in life, and so on. In the 20th century, as modesty began to disintegrate, many of the popes tackled this issue in great depth, giving extremely explicit condemnations of certain trends in fashion, condemning immodesty and calling for very specific guidelines, such as how low and dress can be cut and so forth.

In areas where there has never been any official guidance and modesty is not an issue, however, it has often been difficult to draw a firm line. For example, in the Early Church it was expected that men would have facial hair; St. Cyprian famously encouraged men to refrain from shaving and tried to argue it was a biblical precept. But in the early 20th century in the West, beards were looked upon as sloppy and the Roman rite actually forbid clergy from wearing them. What about long hair on men? This was a fashion for centuries in France and a sign of nobility; again, in the 20th century, as the culture shifted, long hair came to represent something quite different and was seen as a sign of a dissolute. The history of hair in the Christian west has been varied and contradictory.

In many situations, the propriety of a certain styles changed as time passed. Sometimes it is amusing to see where the clergy of any given age fell on these questions of style. In this article, we will look at the writings of the 12th century monastic chronicler Orderic Vitalis and his railings against the fashions of his day.

Who is Orderic Vitalis?

Orderic Vitalis was an English Benedictine who lived from 1075-1142, during the period of the Norman ascendancy. His monastic life was uneventful; he is best remembered for his historical writings, the Historia Ecclesiastica, which was a general history of his own age focusing in on the affairs of the Norman nobility. He is acclaimed as a trustworthy and objective source of information for the goings on of Normandy in the early 12th century.

The span of Orderic’s life saw some truly remarkable events. Born only nine years after the Conquest of England, Orderic was acquainted with many of the men of the previous generation who had participated in the Conquest. He also witnessed the First Crusade unfold before him shortly after he took his monastic profession and was personally familiar with some of the great names of the First Crusade. He lived long enough to witness the Cistercian reform and the fame of St. Bernard of Clairvaux.

Those Medieval Shoes!

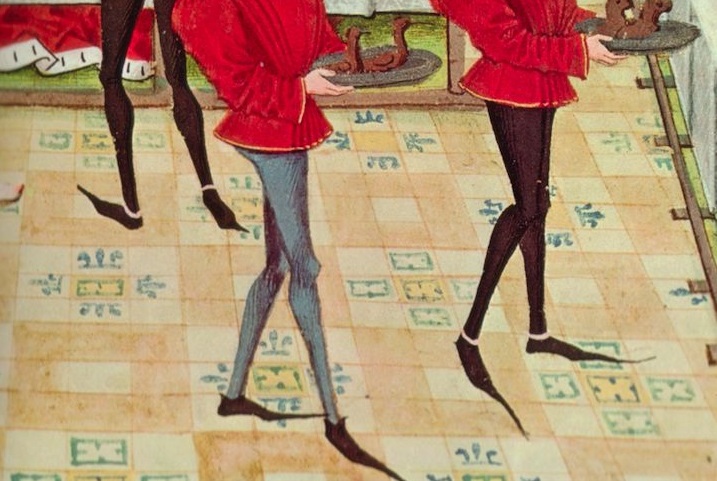

Though there is much of value in Orderic’s writings, here we focus in on an interesting little aside he notes in his Historia Ecclesiastica on the dress of the Norman lords around the year 1100. Orderic believed the male dress of his day expressed a detestable effeminacy that he felt was undermining the role of men in society. He begins his attack on the effeminate fashions of the day by launching a broadside against long-toed medieval shoes:

A debauched fellow named Robert was the first, about the time of William Rufus, who introduced the practice of filling the long points of the shoes with tow [fibers], and of turning them up like a ram’s horn. Hence he got the surname Cornard; and this absurd fashion was speedily adopted by a great number of the nobility as a proud distinction and sign of merit. At this time effeminacy was the prevailing vice throughout the world…” (1)

He goes on to critique the styles of robe and tunic, of parting of the hair, and the wearing of gloves, all of which he associates with effeminacy:

They parted their hair from the crown of the head on each side of the forehead, and their locks grew long like women, and wore long shirts and tunics, closely tied with points…In our days, ancient customs are almost all changed for new fashions. Our wanton youths are sunk in effeminacy. They insert their toes in things like serpents’ tails which present to view the shape of scorpions. Sweeping the dusty ground with the prodigious trains of their robes and mantles, they cover their hands with gloves…Their locks are curled with hot irons, and instead of wearing caps, they bind their heads with fillets [headbands]. A knight seldom appears in public with his head uncovered and properly shaved according to the apostolic precept.” (2)

While we may understand the curling of hair with irons, why shoes with curly toes should be considered effeminate, or wearing gloves for that matter, is inaccessible to us nine centuries out. Obviously it would need to be studied in the context of the fashions and assumptions of that day and age. Perhaps there was a very legitimate reason why Orderic considered these trends unacceptable; or, perhaps like many modern Christians who admit a bit too much of a puritanical strain, Orderic wanted to absolutize what were merely his tastes. We don’t know, and I will refrain from passing any judgments on Orderic’s opinion.

It is very interesting to note, however, that the generation Orderic is condemning for effeminacy is the same generation that went on the First Crusade and stormed Jerusalem. The furious Norman knights who marched to the Holy Land, struck the Muslim kingdoms like lightning, and raised the cross over Jerusalem, proclaiming the Latin Kingdom—these are the same men Orderic considers effeminate. Some of these men may have been old enough to have fought with the Conqueror at Hastings in 1066.

If Orderic considered the Norman barons of the First Crusade effeminate, what then was his model of manliness? Looking back from nine centuries, the Normans of the First Crusade are some of the most manly-men most Catholics can imagine. What did Orderic imagine as his model of Catholic manhood? He unfortunately did not tell us, but it is a fascinating question to think upon.

(1) Orderic Vitalis, Ecclesiastical History, quoted in Henry Adams, Mont-Saint-Michel & Chartres (Anchor Books: 1959), 221

(2) Ibid., 221-222

Phillip Campbell, “Orderic Vitalis on Curly-Toe Shoes,” Unam Sanctam Catholicam, Apr. 25, 2015. Available online at https://unamsanctamcatholicam.com/2023/11/orderic-vitalis-on-curly-toe-shoes