Servant of God Blandina Segale, S.C. (1850-1941) was a Sister of Charity out of Cincinnati who was sent to the western frontier in 1872 as a missionary. Between 1872 and 1893 she bounced around between Trinidad, Colorado, and Santa Fe and Albuquerque, New Mexico, founding schools and hospitals. She had many adventures in the old west, including run-ins with Billy the Kid and other notorious outlaws. She advocated for the rights of Native Americans against American exploitation, and on more than one occasion saved accused persons from lynch mobs. She recorded her adventures in the west in great detail in a diary to her sister, which has been published by the Sisters of Charity out of Cincinnati in a book called At the End of the Sante Fe Trail. It is fantastic reading for anyone interested in the history of the American missions or the Wild West in general.

There are many stories that could be told about Sr. Blandina, but in this essay we will concern ourselves with the attempts of certain anti-Catholics in New Mexico and Colorado to either bring the Sisters of Charity under state guidelines or expel them entirely from public education. But before we tell that story, we must explain how an order of Catholic nuns became involved in the public schools to begin with.

Religious in Public Schools

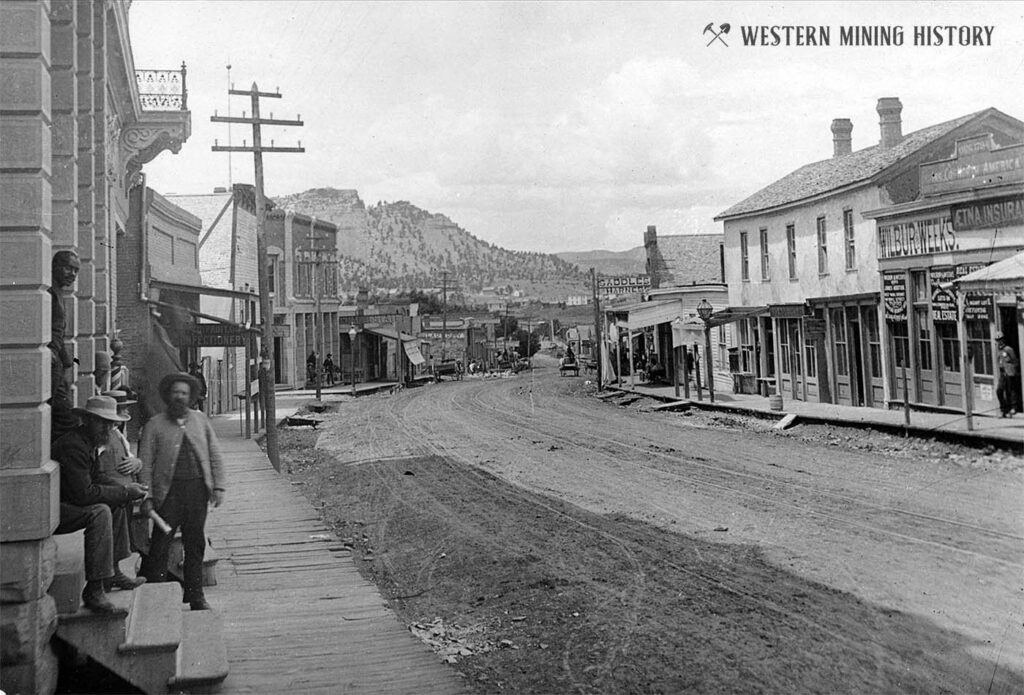

Education was tricky in the days when the frontier was just opening to settlement. One of the first acts of any local government on the American frontier was to open a public school—generally a one room structure where both sexes of all ages were educated in common. But while building the school was one thing, staffing it was another. The sparse population, challenging living conditions, and thin municipal budgets made it difficult to attract teachers to frontier towns.

In these circumstances, lcal governments sometimes turned to religious orders as a means of providing necessary education. As missionaries like the Jesuits, Franciscans, and (in our story) the Sisters of Charity were a common pillar of frontier communities, public authories contracted with them to provide certain services for the public good. Since religious congregations were highly educated, disciplined, and of high moral character—and, as they had no profit motive—they were ideal candidates to teach in frontier schools. Typically the school district would engage their services to teach foundational courses like spelling, reading, and arithmetic (religious classes could be offered to students but had to be taught elsewhere). The religious would be paid a wage out of the public coffers for their time. The arrangement was mutually beneficial: the school district got qualified teachers, and the religious received a steady income stream which could be used to fund their missions, hospitals, etc.

Sr. Blandina’s Sisters of Charity had this arrangement in various of the frontier towns they operated in. Blandina’s sisters managed the public education in Trinidad as well as old Albuquerque, where Sr. Blandina Segale had a reputation for being a kind of educational wonder-worker whose hard work and generosity won the esteem of the entire community. This sort of arrangement was not only sought for education, but other types of public work as well; for example, Sr. Blandina had an agreement with Santa Fe County for the service of burying the dead. She records that the County Commissioners of Santa Fe County paid the Sisters of Charity a stipend of $8.00 per burial in the late 1870s. A lot went into this. Sr. Blandina explains what that $8.00 entailed in a diary entry:

The county has been allowing us $8 for every indigent patient who dies and whom we bury…that is, we prepare the deceased for burial, procure the grave and have it dug, make the coffin and transport the body to its resting place. To this I add a wreath of flowers, and when I return from the graveyard, I invariably write to those connected with the deceased, mentioning the fact that, in lieu of his having passed to God among strangers, we endeavored to supply the place of those who loved him by giving full attention to his needs, after which we placed a wreath of flowers on his coffin and accompanied him to his place of rest. (1)

The problem, of course, was what to do when these settlments grew and the municipal government no longer needed the sisters’ assistance. Sometimes local governments attempted to use the growing population as leverage to force the sisters into accepting lower wages. Sr. Blandina records that in 1880, she entered into a dispute with the County Commissioner of Santa Fe over the cost of burials. The rising population of the county and increasing pressures on the sisters’ time made it more difficult to do all this work for $8.00. Sr. Blandina insisted that the Commission raise the stipend to $15.00, but the Commissioner fought to keep the previous rate of $8.00 (Blandina believed this was because a certain amount was allocated for every burial, and the Commissioner got to pocket the difference between the line item expense and whatever he paid the sisters). The Commissioner refused to budge until Blandina threatened to have the dead bodies dumped at his office, after which he quickly acquiesced to $15.00. (2)

The Albuquerque Teachers’ Public Examination

By 1891, the community of Albuquerque had grown considerably. Whereas it was once difficult to find qualified teachers, the school board now had more options. Furthermore, as the town expanded, there came with it an increasing formality of management by the new generation of administrators, who did not approve of the contract with the sisters. Part of this hostility was simply the mistrust that administrators have for outside contract help they cannot fully control, but it was also due to the emergent educational reform movement that would dominate American education at the turn of the 20th century. The education reform stressed credentialing, systemization, and protocol. They were suspicious of Blandina and her sisters since they were not formally trained teachers. And—though it’s harder to quantify—we must also mention recurrent bouts of anti-Catholic bigotry, the idea that it was somehow un-American for Catholic nuns to be teaching in public school.

Consequently, the Superintendent of Schools made a concerted effort to get Sr. Blandina and her nuns out of Albuquerque’s public education. The efforts were led by an unnamed opponent of the sisters whom Blandina describes as “habitually intoxicated.” The effort seems to have had the backing of a considerable number of Albuquerque’s residents. Blandina was back at her mission in Trinidad, Colorado when the attack came. She wrote:

Mother Blanche received wires and letters from Albuquerque to have me there for a few weeks. The reason is most laughable. A young man whom I prevented from being sent to the penitentiary by adjusting his case out of court , and who is habitually intoxicated, is leading a faction of our natives to compel the sisters to give up the public schools of Old Town! (3)

When Blandina arrived in Albuquerque, she found that the attempt to eject the sisters took the form of a law mandating a compulsory examination to be taken by every public school teacher. Since the Sisters of Charity had no formal educational training, it was assumed that they would fail the exam, or likelier, not turn up for the exam at all. “That young inebriate counts upon the idea that the Sisters will not go to a public assembly to take the Teachers’ public school examination,” Blandina wrote in her diary. “In this case, I clearly see it is of vital importance for the Sisters to take the examination, wherever it will be held.” (4)

Blandina records that on the day of the examination (which was held publicly in the court house), the entire community had turned out to witness the spectacle:

The Teachers Examination today. The Court House is filled to capacity. There are three tables in the enclosure usually occupied by Court officials and separated from the audience by a neat wooden railing. The Sisters—four of us—were assigned to one oblong table. Next to us were placed a number of young ladies—most of them former pupils. Parallel to their table sat a goodly number of teachers and aspiring teachers. The examination papers were distributed. (5)

The examination had a reputation for being difficult. Blandina had scarcely begun when former Congressman and Bernalillo County Commissioner Mariano Otero walked over to Blandina to, as she put it, “condole with me over the difficult examination questions.” (6) Blandina at first though this was a comment of derision, for she found the questions easy enough that “any fourth year high school pupil could answer them” (7). But the comment was in earnest, for as the test went on she noticed several other examinees give up and walk out in frustration at the apparent difficulty of the questions.

A few days after the exam, the President and members of the Examination Board came to Sr. Blandina’s convent in a group to present their certificates, saying, “We want the pleasure of personally handing you the first four Number One teachers’ certificates issued in Albuquerque under the new school law.” (8) Sr. Blandina and her sisters were thus the first certified public school teachers in the New Mexico Territory.

Though Blandina had successfully navigated this first attempt to get the sisters out of the public schools, she knew the age of this sort of public-religious collaboration was drawing to a close. Education was becoming too highly politicized. She wrote to her sister after the affair:

You must take into account, Sister Justina, that thi is the first Teachers’ Public Examination ever held in this Territory. This covers all territory, but does not hide from me the fact that before long all school funds will be diverted into channels dug out by politicians. The only available public school funds for nuns will be the country schools where politicians will not find persons to teach except the “benighted Catholics.” (9)

The School Board of Trinidad, Colorado.

The Sisters of Charity had taken on the responsibilities of public education in Trinidad, Colorado under the the auspices of Sr. Blandina early in the 1870s. Trinidad was Sr. Blandina’s first mission, when she was only twenty-two. The Sisters of Charity continued on in the Trinidad public schools for years after Blandina moved on to Albuquerque, becoming an integral part of the community and a pillar of the school system.

In 1892 Blandina was back in Trinidad and found problems with the school board similar to what she experienced in Albuquerque. Sr. Blandina attributed this to sheer anti-Catholic bigotry. As early as 1889 she had predicted trouble in Trinidad. On August 11, 1889, she wrote her sister explaining her misgivings:

I am to resume my first school work in the Southwest, Number One School in Trinidad. I’m a false prophet if the Sisters of Number One public school in Trinidad, Colorado, will not be forced to resign. I’ve watched the trend of bigotry. We have set the example of liberality and blazed a path or morality and self-sacrifice—all that remains to us now is to be sacrificed. (10)

Blandina was prescient on this account. Like the Persian satraps of old who said, “We shall not find any ground for complaint against this Daniel unless we find it in connection with the law of his God” (Dan. 6:5), so the enemies of the sisters’ teaching in public schools devised an attack that struck at the very heart of their religious identity. The schools in Colorado had recently been made subject to a new rule prohibiting the wearing of religious habits by teachers. The law compelled all religious to either resign their teaching offices, or else adopt secular dress.

In summer of 1892, Blandina was brought before the school board of Trinidad to discuss the matter. The school board notified her that “under no circumstances does the school board want to lose your services, but we ask you to change your mode of dress.” (11) Sister Blandina needed but a moment to formulate her response. In her own words, she told the school board:

The Constitution of the United States gives me the same privilege to wear this mode of dress as it gives you to wear your trousers. Good-bye.” (12)

And with that she left the meeting. The school board was flabbergasted, having assumed that Blandina would not so swiftly walk away from an educational apostolate she had nurtured for two decades. But for Sr. Blandina Segale, the religious habit was integral to her identity as a consecrated woman and she was willing to part with anything in order to preserve it. She tells us that when a week went by and the school board realized she would not compromise, the board secretary sent her a tersely worded telegram reaffirming their demands for compliance:

Sister Blandina June 17, 1892

Trinidad, Colorado

Dear Madam,I am requested by the School Board—as Secretary of the Board—to notify you and Sister Rose Alexius that your applications as teachers in the public schools of Trinidad, Colorado, for the coming year can only be accepted upon the condition that you shall lay aside your dress of black, peculiar to your church and office, and be willing to comply with all the rules of the Board and Superintendent—the same as is required of all other teachers in the Trinidad Schools.

Very respectfully,

Trinidad School Board

Per E. Brigham, Secretary (12)

It seems that Mr. Brigham and the Trinidad School Board were not entirely behind the new regulation, enforcing it only of reluctant necessity, as the telegram contained the following post-script, wherein we see the Board attempting to assure Sr. Blandina that they are forcing her out only in order to avoid their own difficulties:

P.S. Sister Blandina, you understand full well that your qualifications as a teacher are not questioned, and also those of Sister Alexius are quite satisfactory. But you understand full well our position and that anything in a public school that savors of sectarianism brings us into trouble and is directly in opposition to all our school laws, and the duties required of School Directors, hence there is but one course of action, and that must be in the line of our duty and you can but say that we are justified in this matter. (13)

It seems clear that the school board would have preferred to keep Blandina teaching if they could, just under their terms. But Blandina would have none of it. When she communicated the matter to her Mother Superior, she was lovingly told, “You foresaw this. God ever bless you. St. Patrick’s School in Pueblo, Colorado needs a principal—fill the vacancy.” (14) Blandina and her sisters clearly believed their identity as religious—as exemplified by their habits—took precedence over any sort of active work in the community.

Though Sister Blandina dutifully obeyed, she did so with a broken heart. In a letter to her sister, she pours out the distress at walking away from a two decade apostolate under such ignominious circumstances. The pain is clearly discernible in her words, which, speaking of herself in the third person, read rather more like a eulogy:

So this is the end of twenty-two years’ work in Public School Number One, opened in 1870 when Trinidad was mostly governed by the best shotmen and sheriff’s lead, mobs to hang murderers, and jail birds never come to trial, and the life of a man was considered a trifle compared to the possession of a horse. Jesuits and Sisters used every effort to quell the daily storms—while School Room in School Number One exerted an influence over the pupils—grown men and women—attending Room Number One that often astonished its teacher.

Money considerations never entered the mind of her who had early in life evaluated money and eternity. We supplied the school building, janitor, and made repairs, and daily from the one story adobe building went forth cleaned hearts that had entered with murderous thoughts and designs; hearts filled to overflowing with the desire to get rich quick; hearts whose morality was fit companion to the beasts of the plains; and these spasmodically agitated hearts were quelled to calmness by her whose sole thought was peace—the path to Heaven…Adios, Trinidad, of heart-pains and consolations! (15)

Sister Blandina would go back to Albuquerque in 1901 where she oversaw the construction of St. Joseph Hospital. Eventually she returned to Cincinnatti to minister to the Italian Catholic community there. She lived till the ripe old age of 91, dying on February 23, 1941. Her cause was opened in 2014 by the Archdiocese of Sante Fe, New Mexico. Blandina Segale, ore pro nobis!

(1) Blandina Segale, At the End of the Santa Fe Trail (Sisters of Charity: Cincinnatti, 2014), 150

(2) Ibid., 151-152

(3) Ibid., 279

(4) Ibid.

(5) Ibid.

(6) Ibid.

(7) Ibid.

(8) Ibid., 280

(9) Ibid.

(10) Ibid., 273

(11) Ibid., 281

(12) Ibid., 282

(13) Ibid.

(14). Ibid.

(15) Ibid., 281, 283

Phillip Campbell, “Sister Blandina vs. the Public Schools,” Unam Sanctam Catholicam, Mar, 10, 2024. Available online at https://unamsanctamcatholicam.com/2024/03/sister-blandina-vs-the-public-school