The discipline of clerical celibacy is a common point of dispute between the Latin Church and the Eastern churches, both those in and out of union with Rome. Eastern Christians allow a married, sexually active priesthood while the Latin Church has always insisted on sexual continence from its clerics. This discussion is often framed in such a way that the East is said to be preserving a very ancient tradition in the while the West is maintaining a tradition that “only” dates from the 10th century. Implicitly, the Eastern discipline is given a more credible historical pedigree, as if a sexually active priesthood is the more ancient custom. In fact this is not the case. The Latin custom of perfect continence for clerics is actually much more ancient than the current Eastern tradition, which dates from the Quinisext Council of 691-692. In this article, we will examine the historical and canonical questions surrounding this council and demonstrate that the Quinisext Council in Trullo represented a major rupture with tradition. A married priesthood was not, in fact, the Eastern tradition, but a compromise and a novelty introduced at the end of the 7th century.

Priestly Celibacy in the Early Church: Preliminary Reading

Before delving into the details of the Quinisext Council, we recommend some preliminary reading to get acquainted with the particulars of priestly continence in the early Church. Unam Sanctam Catholicam articles dealing with this topic are “Truth About Priestly Continence and Celibacy in the Early Church“, our book review of Apostolic Origins of Priestly Celibacy by Fr. Christian Cochini, S.J., and our article “Council of Ancyra and Celibacy.” Although this essay can stand alone, we recommend reading the above-mentioned articles to get a better grasp of the subject matter, which is by no means simple.

The Historical Context of the Quinisext Council

It is very important to understand the Quinisext Council in its historical context. The Quinisext Council—sometimes called the Council in Trullo (“under the dome”, referring to the domed hall in which it was held), was summoned in the year 691 during the reign of Justinian II. The council was attended by 215 fathers, mainly Greeks with a smattering of Armenians and other easterners. The purpose of the council was to attend to urgent disciplinary matters, for the affairs of the Eastern Church were then in disarray.

There are two fundamental historical considerations that must inform our study of the Quinisext Council: first, the rapid disintegration of the Byzantine Empire in the 7th century; second, the Byzantine animus against Rome, which had come to a head by the time of the Quinisext Council.

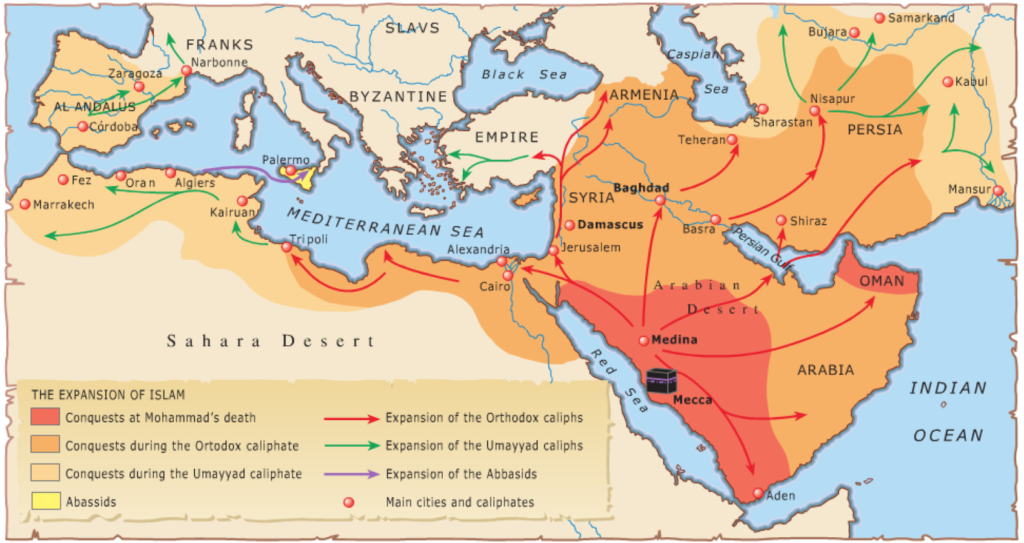

The Byzantine Empire in the 7th century was in a state of disarray approaching total collapse. This was due in part to the explosion of the Islamic hordes out of Arabia, which in the seven short years from 635 to 642 had wrested Egypt, Syria, Palestine, and Mesopotamia from the Byzantines. Nor were the north and western frontiers safe, for the Slavs and Bulgars had seized Illyria and were rampaging around Macedonia and even pillaging Greece itself. Byzantium was pressed by enemies on all sides and had not a moment to rest or gather her wits; by the time she had a blinked, 60% of Byzantine territory was irretrievably lost.

The chaos of the period is reflected in decline in all the major indicators of culture. Except for a few monastic hagiographies, there was a cessation of writing. No major architectural projects are known from the period. Art went into regression. The era was characterized by a deep malaise and gloom which seemed to cast an uncertain shadow over the future. The condition of the East in the late 7th century can probably be compared to the Western Roman Empire in the decades before its collapse. To those Christians living in the Byzantine Empire at the time, it must have seemed that the Christian world itself was coming to an end.

This had obvious reprecussions on clerical discipline. Historically, ecclesiastical discipline is only able to be maintained in conditions of temporal peace. It is evident that clerical discipline cannot be upheld when the future of civil society itself is uncertain; chaotic historical epochs, while not without instance of individual heroism and sanctity, are generally periods when laxity and abuses creep into the clergy. This was certainly the case in the East in the 7th century, if only because communication between the churches was cut off as vast swaths of territory were swallowed beneath the Muslim tide. Of course, such a breakdown in communications also meant a breakdown in oversight, which in turn wore down discipline.

By 691 the situation had partly stabilized, enough at least for the fathers of the East to gather in the Quinisext Council and discuss remedying the abuses that had arisen over the past fifty years. The chaos of this period should be kept in mind when examining the details of the canons of the Quinisext Council.

The second historical consideration in discussing the Quinisext Council in Trullo is the ever-widening breach between East and West, or more particularly, between the See of Constantinople and the See of Rome. Though the fractious history between the Greek and Latin Churches is too voluminous to attend to here, one point at least must be considered as an immediate precursor to the Quinisext Council: the 7th century disputes between Rome and Constantinople over the heresy of Monothelitism.

The background of the Monothelitist heresy is long and convoluted, as one can tell by even a cursory perusal of the Catholic Encyclopedia’s entry on the issue. We can scarcely hope to explore it here, but it suffices to say that the heresy had its origin in the attempts of the Byzantine Emperor Heraclius (r. 610-641) to reach some sort of theological compromise with the Monophysites, who in the 7th century had strong majorities in Egypt and Syria. Monothelitism was a sort of middle ground between orthodoxy and Monophysitism, which, instead of positing one will in Christ (Monophysitism) agreed in professing two wills but stated there was only one action or “energy” (energeia) for both wills.

This doctrine was officially promulgated by Heraclius in a document called the Ecthesis issued in 638. After some turmoil, the Ecthesis was accepted by all of the Patriarchs of the East. The document, however, was rejected by Pope Severinus and condemned outright by Pope John IV in a solemn synod. This outraged Heraclius; his grandson and successor Constans II initiated a ferocious persecution of the orthodox which only ended with his death in 668. After this, the Monothelitist moment ended and Monothelitism was formally condemned in the Third Council of Constantinople (681-681). Nevertheless, there was a lingering attitude of resentment towards Rome for what many bishops believed was an unwarranted interference of the west upon the affairs of the east. Rome was instrumental in resolving the Monothelitist schism, yet the prominent role Rome played in the affair only strengthened the resolve of the Eastern sees to assert their independence, fearing the prestige of the Roman See detracted from their own autonomy.

The Quinisext Council was summoned by Justinian II in 691 was thus convened in an atmosphere of open hostility towards Rome. The disciplinary collapse in the frontiers of the Byzantine world offered the council fathers the occasion they needed to legislate in such a manner that would assert their independence from the See of Rome. Hence, the legislation that came out of the Quinisext Council in Trullo would go out of its way to emphasize and even promulgate disciplines which were in open rupture with those of the West and, as we shall see, even with the Eastern tradition itself.

Clerical Continence in the Byzantine Empire

It is important to note that, contrary to what the Orthodox will claim, a married priesthood was not the tradition in the East, at least not in the way that current apologists of the Orthodox discipline mean. Everybody knows that East and West both admitted married men to Holy Orders in the Early Church. What is not so widely understood is that the universal discipline was that once a man was admitted to the diaconate (or in some instances, even the subdiaconate) he was expected to remain continent, whether he was married or not. This means that while married men were often admitted to Major Orders, they were expected to forgo sexual relations with their wives once they were ordained. This was practiced not only in the West but in the East as well, as is attested by Origen, Eusebius, St. Cyril of Jerusalem, the Council of Nicaea, the Council of Ancyra, St. Ephrem the Syrian, St. Gregory the Illuminator, St. Jerome, St. Epiphanius, and St. John Chrysostom—all Easterners.

Thus the East and the West both ordained married men to the priesthood, but there was never tolerance for a sexually active priesthood. Clerical continence was the norm in both East and West. We will not take the time now to establish this point; it is already well established historically, and for readers who want more background on this discipline we recommend the three articles linked above at the top of this essay.

The question was what to do when this discipline broke down, as it often did in periods of confusion. In Spain, the observance of the discipline faltered in the midst of the chaos that attended the conversion of the Visigoths to Christianity and again during the conflict between the Arian and Catholic factions. In Gaul, the discipline broke down in the midst of the wars that cut her off from the failing Western Roman Empire and saw the emergence of the Merovingian kingdom in the late 5th century. In both cases, once peace was restored, the bishops of Spain and Gaul restored the ancient discipline of clerical continence with utmost severity, even resorting to banishment or imprisonment of offenders. Eventually the discipline of clerical continence was restored in both Spain and Gaul.

In Byzantium, however, the problem was handled differently. Like Spain and Gaul, Byzantium had suffered a breakdown of discipline. In the chaos attendant upon the Muslim invasions, many married priests in the East began to illicitly resume conjugal life with their wives. The Quinisext Council, rather than take the rigorous approach of Spain and Gaul, chose a compromise approach which would reconcile these priests while simultaneously allowing them to maintain conjugal lives with their spouses, as we shall see. So while the problems were the same in the East as in the West, the approach taken in Byzantium was one of compromise rather than rigor.

What accounts for Byzantium’s divergent approach? This is a matter of conjecture, but it may have been due to the prevalence of other heresies in the East. Whereas all the early heresies had died out in the West by 691, the East at the time was still rent asunder by heretical sects. The Armenians adhered to the newly formed gnostic Paulicians. Large tracts of Mesopotamia, Palestine, and Syria had been lost to the Nestorians. Egypt was entirely Monophysite, while the theological meddling of Emperor Heraclius left a considerable smattering of Monothelitists scattered throughout the East. Without exception, all of these other sects allowed married priests full use of their conjugal rights.

Thus, while lax clerics in the West really had no other parallel church to turn to, the plethora of schismatic churches in the East meant that the lax cleric had many options if he fell afoul of Orthodox discipline. If the See of Constantinople would not sanction his common life with his spouse, the Nestorian, Monophysite, Paulician or Monothelitist congregations would. In other words, the Western bishops had a stronger hand in the enforcing of the discipline than did those of the East.

The Eastern bishops thus faced a strong pressure to compromise on this issue that the Latins did not. And recall, this is all against the backdrop of the dismemberment of the Byzantine Empire by the Islamic hordes, which would have given an added sense of urgency to finding a compromise that would allow the clergy to continue to minister without burdening them unnecessarily.

This is not to excuse the Eastern bishops for seeking a compromise; we seek here only to understand the rationale for what occurred at the Quinisext Council, to which we will now turn.

The Canons of the Quinisext Council in Trullo

We have already noted that the discipline in the universal Church was that clerics should be sexually continent. This means that bachelors ordained observed celibacy, while the married ordained abstained from sexual relations with their spouses. When looking at the canons of the Quinisext Council, we can see that they attempted to maintain continuity with this tradition in several respects. For example, canon 12 prohibits a married bishop from cohabiting with his wife. Canon 12 states:

Moreover this also has come to our knowledge, that in Africa and Libya and in other places the most God-beloved bishops in those parts do not refuse to live with their wives, even after consecration, thereby giving scandal and offense to the people. Since, therefore, it is our particular care that all things tend to the good of the flock placed in our hands and committed to us—it has seemed good that henceforth nothing of the kind shall in any way occur. And we say this, not to abolish and overthrow what things were established of old by Apostolic authority, but as caring for the health of the people and their advance to better things, and lest the ecclesiastical state should suffer any reproach. For the divine Apostle says: Do all to the glory of God, give none offense, neither to the Jews, nor to the Greeks, nor to the Church of God, even as I please all men in all things, not seeking my own profit but the profit of many, that they may be saved. Be imitators of me even as I also am of Christ. But if any shall have been observed to do such a thing, let him be deposed.

This problem is again taken up in canon 48:

The wife of him who is advanced to the Episcopal dignity, shall be separated from her husband by their mutual consent, and after his ordination and consecration to the episcopate she shall enter a monastery situated at a distance from the abode of the bishop, and there let her enjoy the bishop’s provision. And if she is deemed worthy she may be advanced to the dignity of a deaconess.

The canons do not mention sexual abstinence specifically. It is cohabitation that is a problem and which is presumed to be a scandal to the faithful, as canon 12 mentions. But common sense dictates that the reason cohabitation is a scandal is because of the presumption of conjugal intercourse. The canons of Quinisext obviously want to protect the faithful from the scandal of their bishops having sexual intercourse with their spouses and hence mandate the physical separation when a married man is advanced to the episcopate. In these two canons, there is a striking continuity with the Latin discipline, which also favored physical separation of married bishops from their spouses in legislation from the same period.

Canon 3 deals at length with the particulars of clerical marriage:

Since our pious and Christian Emperor has addressed this holy and ecumenical council, in order that it might provide for the purity of those who are in the list of the clergy, and who transmit divine things to others, and that they may be blameless ministers, and worthy of the sacrifice of the great God, who is both Offering and High Priest, a sacrifice apprehended by the intelligence: and that it might cleanse away the pollutions wherewith these have been branded by unlawful marriages: now whereas they of the most holy Roman Church purpose to keep the rule of exact perfection, but those who are under the throne of this heaven-protected and royal city keep that of kindness and consideration, so blending both together as our fathers have done, and as the love of God requires, that neither gentleness fall into licence, nor severity into harshness; especially as the fault of ignorance has reached no small number of men, we decree, that those who are involved in a second marriage, and have been slaves to sin up to the fifteenth of the past month of January, in the past fourth Indiction, the year six thousand one hundred and nine [AD 692], and have not resolved to repent of it, be subjected to canonical deposition: but that they who are involved in this disorder of a second marriage, but before our decree have acknowledged what is fitting, and have cut off their sin, and have put far from them this strange and illegitimate connection, or they whose wives by second marriage are already dead, or who have turned to repentance of their own accord, having learned continence, and having quickly forgotten their former iniquities, whether they be presbyters or deacons, these we have determined should cease from all priestly ministrations or exercise, being under punishment for a certain time, but should retain the honour of their seat and station, being satisfied with their seat before the laity and begging with tears from the Lord that the transgression of their ignorance be pardoned them: for unfitting it were that he should bless another who has to tend his own wounds.

But those who have been married to one wife, if she was a widow, and likewise those who after their ordination have unlawfully entered into one marriage that is, presbyters, and deacons, and subdeacons, being debarred for some short time from sacred ministration, and censured, shall be restored again to their proper rank, never advancing to any further rank, their unlawful marriage being openly dissolved. This we decree to hold good only in the case of those that are involved in the aforesaid faults up to the fifteenth (as was said) of the month of January, of the fourth Indiction, decreeing from the present time, and renewing the Canon which declares, that he who has been joined in two marriages after his baptism, or has had a concubine, cannot be bishop, or presbyter, or deacon, or at all on the sacerdotal list; in like manner, that he who has taken a widow, or a divorced person, or a harlot, or a servant, or an actress, cannot be bishop, or presbyter, or deacon, or at all on the sacerdotal list.

The text of the canon is long, but the import is simple. First, second marriages among the clergy are absolutely forbidden. Those who have entered into second marriages (i.e., widowers who have remarried) are “slaves to sin.” They are called to return to continence and can be restored to ministry after a period of penitence. Those who refuse will be deposed. Second, it is unlawful for priests, deacons and subdeacons to contract marriage. Those who have done so have their marriages declared null and will be restored to ministry after a period of penance. Finally, no man who has been married twice or who is married to a disreputable woman can ever be advanced to Major Orders.

Note also, however, that the canon also admits that the council is taking a route of moderation. The See of Rome is said to “keep the rule of exact perfection” in this matter; the Byzantines, by contrast, take an approach of “blending both” leniency and rigor together. (1) The Byzantines are thus arguing their discipline is more moderate and balanced than the “rule of exact perfection” observed by the Latins. This is the blending that the Quinisext fathers speak of.

Canon 13 of the Quinisext Council in Trullo

Henceforth we have seen how much of the teaching of the Quinisext Council is actually in harmony with the traditions of the West, as well as with previous Eastern traditions. It is in canon 13, however, that we see the introduction of a great novelty with the allowance of married priests and deacons to use their conjugal rites, something unknown in antiquity but the result of the council’s approach of “blending” severity with lenience in order to stop her priests from hemorrhaging over to the heretical sects. Canon 13 states:

Since we know it to be handed down as a rule of the Roman Church that those who are deemed worthy to be advanced to the diaconate or presbyterate should promise no longer to cohabit with their wives, we, preserving the ancient rule and apostolic perfection and order, will that the lawful marriages of men who are in holy orders be from this time forward firm, by no means dissolving their union with their wives nor depriving them of their mutual intercourse at a convenient time. Wherefore, if anyone shall have been found worthy to be ordained subdeacon, or deacon, or presbyter, he is by no means to be prohibited from admittance to such a rank, even if he shall live with a lawful wife. Nor shall it be demanded of him at the time of his ordination that he promise to abstain from lawful intercourse with his wife: lest we should affect injuriously marriage constituted by God and blessed by his presence, as the Gospel says: What God has joined together let no man put asunder; and the Apostle says, Marriage is honourable and the bed undefiled; and again, Are you bound to a wife? Seek not to be loosed. But we know, as they who assembled at Carthage (with a care for the honest life of the clergy) said, that subdeacons, who handle the Holy Mysteries, and deacons, and presbyters should abstain from their consorts according to their own course [of ministration]. So that what has been handed down through the Apostles and preserved by ancient custom, we too likewise maintain, knowing that there is a time for all things and especially for fasting and prayer. For it is meet that they who assist at the divine altar should be absolutely continent when they are handling holy things, in order that they may be able to obtain from God what they ask in sincerity.

If therefore anyone shall have dared, contrary to the Apostolic Canons, to deprive any of those who are in holy orders, presbyter, or deacon, or subdeacon of cohabitation and intercourse with his lawful wife, let him be deposed. In like manner also if any presbyter or deacon on pretense of piety has dismissed his wife, let him be excluded from communion; and if he persevere in this let him be deposed.

First, note the anti-Roman orientation of this canon; the tradition of the Roman Church is acknowledged, but the council fathers go to great lengths to distance themselves from the Latin tradition, which they implicitly condemn. Their citations of Mark 10:9, Heb. 13:4 and 1 Cor. 7:27 are all inapplicable, since separation of bed and board for the purpose of keeping clerical continence is not to dissolve the marriage bond.

The teaching of Quinisext allows married subdeacons, deacons and priests (but not bishops) to use their conjugal rights “at a convenient time”, by which is meant when they are not ministering at the altar. Despite its novelty, the council still sees continence as a prerequisite for serving at the altar. Hence it prescribes periods of continence surrounding a priest’s service at the altar interspersed with allowable use of conjugal intercourse “at a convenient time.” The tradition, on the other hand, both in East and West, saw the priest’s necessity of abstinence as perpetual. Because he was praying and offering sacrifice or administering sacraments continually, the priest was expected to observe perpetual continence.

Canon 13 bases its teaching on two authorities: the Apostolic Canons and a vague reference and paraphrase of “they who assembled at Carthage.” The former is a reference to the Apostolic Canons, a 5th century forgery that was widely accepted in the late patristic era. The specific reference is to the sixth Apostolic Canon, which reads “Let not a bishop, presbyter, or deacon, put away his wife under pretense of religion; but if he put her away, let him be excommunicated; and if he persists, let him be deposed.”

Setting aside the spurious nature of these canons, it must be noted that the text of the sixth Apostolic Canon does not in any way preclude clerical celibacy. It merely stipulates that a married cleric cannot, under the pretense of piety, divorce his wife, but must continue to care for her. Pope St. Leo the Great had noted the same thing in his letter to Bishop Rusticus of Narbonne:

The law of continence is the same for the ministers of the altar, for the bishops, and for the priests; when they were still lay people or lector, they could freely take a wife and sire children. But once they have reached the ranks mentioned above, what had been permitted is no longer so. This is why, in order for their union to change from carnal to spiritual, they must, without sending away their wives, live with them as if they did not have them, so that conjugal love be safeguarded and nuptial activity be ended.” (2)

We see that respect for the marital bond demands that the wife not be dismissed or sent away. The married cleric remains a married man with all the duties to care for his spouse. Only the conjugal rights of marriage are now prohibited; the sexual relationship of the man and his wife is considered elevated “from carnal to spiritual”. This balanced approach allows “conjugal love to be safeguarded” even while “nuptial activity be ended.” Clearly this is not a violation of the sixth Apostolic Canon.

We should note, however, that the sixth Apostolic Canon seems to contradict canon 12 of the Quinisext Council, which we cited above. The former canon prohibits even a bishop from “putting away his wife” under the pretense of piety, while the 12th canon of Quinisext mandates just the same. It could be objected that “putting away” one’s wife means divorce, while clearly canon 12 merely envisions a separation of spouses without dissolving the marriage bond. If this be granted, then the scriptural arguments cited against the Roman custom in Quinisext canon 13 fail because they are based on the same supposition. Thus, either the arguments against the Roman practice in Quinisext Council canon 13 are faulty or canon 12 of Quinisext is in contradiction to the sixth Apostolic Canon.

Misrepresenting the Carthaginian Canons

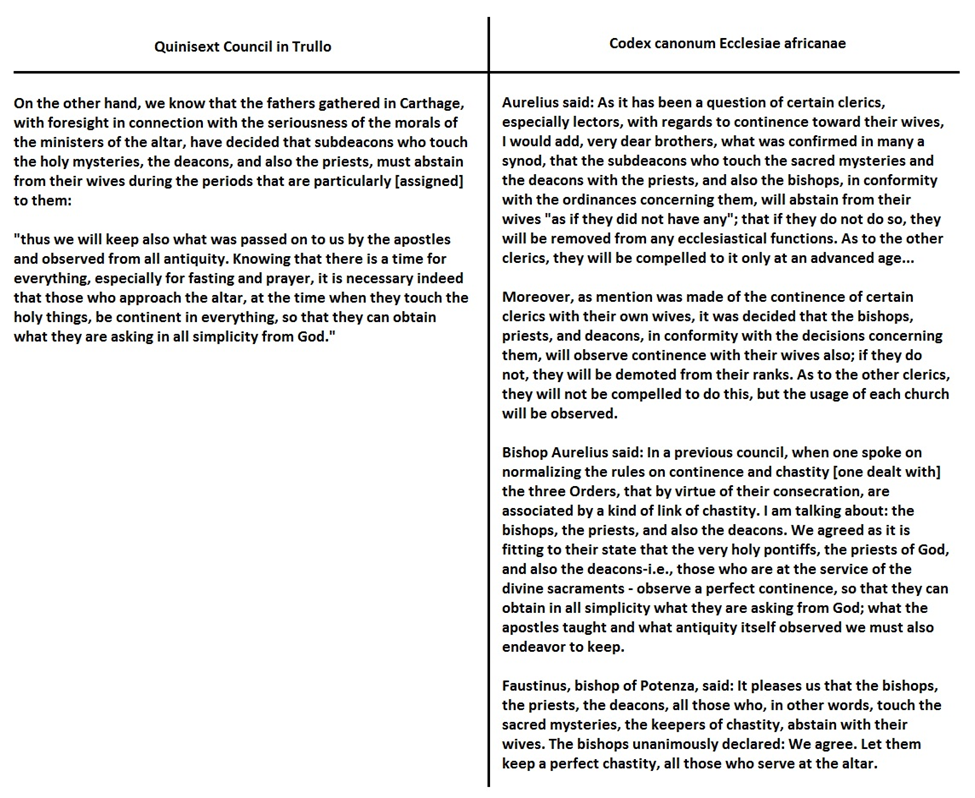

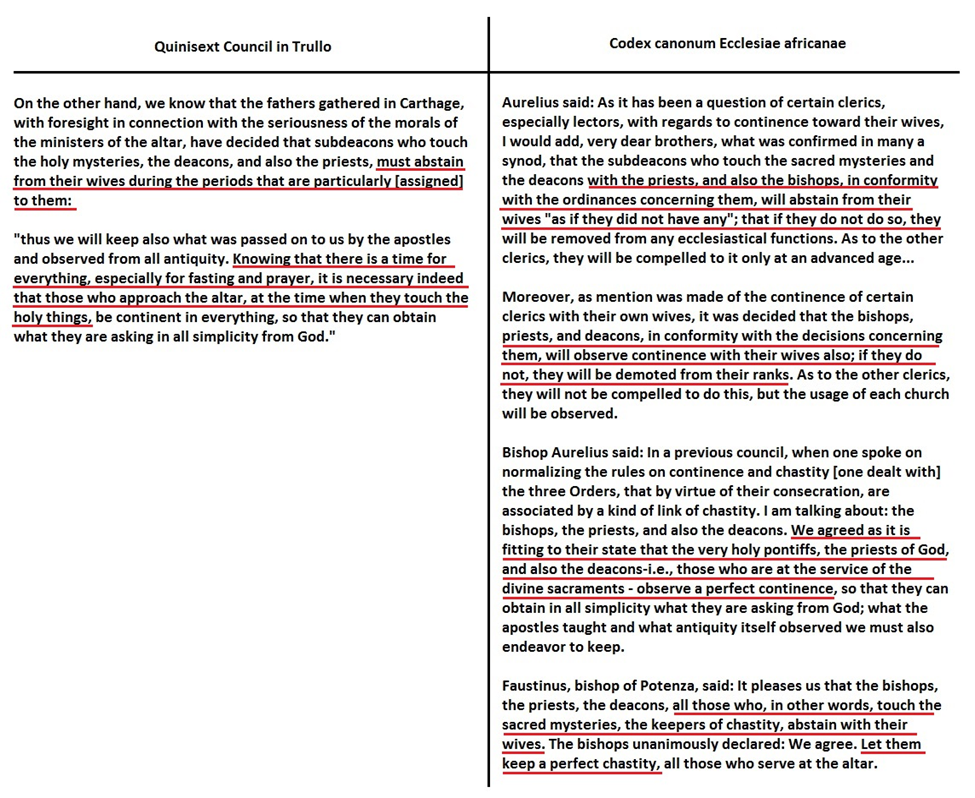

There are greater difficulties, however, when we turn to the council’s citation of the “they who assembled at Carthage.” The reference is to a collection of North African canons called the Codex canonum Ecclesiae Africae, assembled in 419 and themselves consisting of a compilation of canons from two earlier councils held at Carthage in 401 and 390. Here we see the Quinisext Council fathers engaging in blatant misrepresentation of the canons promulgated at Carthage.

Remember, the teaching of Carthage, as summarized by the Quinisext Council’s canon 13, is that clerics should observe a temporary chastity when serving at the altar. In the words of canon 12, it has been

“handed down through the Apostles and preserved by ancient custom, we too likewise maintain, knowing that there is a time for all things and especially for fasting and prayer. For it is meet that they who assist at the divine altar should be absolutely continent when they are handling holy things, in order that they may be able to obtain from God what they ask in sincerity.”

This purports to be a loose citation of the Codex canonum Ecclesiae Africae of Carthage. However, in fact the canons of Carthage make no such provision for any temporary chastity. In fact they call for nothing less than perfect and perpetual continence for all clerics in Major Orders. The teaching of Quinisext canon 13 represents not only a blatant and intentional rupture with the West, but with a universal custom that was observed even in the East until the 7th century.

To make it clearer in what way canon 13 misrepresents the canons of Carthage, consider the relevant texts side by side:

As the text of the Carthaginian is somewhat more verbose than the Quinisext summary, let us look at them again, this time with the pertinent sections underlined in red. Compare the red sections in the left with those from the right:

The phrase “at the time when they touch the holy things” is not found in the Carthaginian canons. There is no hint of a temporary continence in the canons of Carthage; on the contrary, clerics are enjoined to “keep a perfect chastity,” to “abstain with their wives,” to “observe a perfect continence” which is “fitting to their state” and to “observe continence with their wives” or else face demotion from their rank! In other words, the canons of Carthage are in perfect harmony with the discipline as it existed throughout the entire Church until the Quinisext Council.

Clearly the fathers of the Quinisext Council are guilty of taking the canons of Carthage out of context—and not only out of context, but of actually fabricating an exception (“at the time when they touch the holy things”) that did not exist in the original text. We do not here speculate on the degree of malice or culpability involved, but it is undeniable that a fraud was perpetrated in basing the concept of temporary chastity on the canons of Carthage.

In case there be any doubt that this represented a novelty, we need only look at the response of the papacy to the canons of Quinisext. The pope at the time was Pope Sergius I (687-701), who when he heard about the canons, stated that he preferred “to die rather than consent to erroneous novelties” and wrote that the Eastern bishops were the emperor’s “captive in matters of religion.” (3) It is important to note that Sergius himself was a Greek pope, hailing from Syria. If anyone knew the Eastern tradition, it was Pope Sergius. And yet he recognized that the canons of Quinisext were not in continuity with the Eastern tradition but rather represented “erroneous novelties.” He refused to sign the canons when presented to him, for which Justinian II ordered his abduction, although the pope managed to escape.

Were a sexually active married priesthood a legitimate expression of the Eastern tradition, Pope Sergius, a Greek, would certainly not have condemned it as a novelty.

Conclusion

The canons of the Quinisext Council were the most influential disciplinary canons in what would become Eastern Orthodoxy. To this day they remain the framework for Orthodox discipline. Many in the East and West, ignorant of history, have parroted the talking point that a married, sexually active clergy is an ancient tradition in the East while the Western custom of clerical celibacy did not arise until the Gregorian Reform, that the East maintain the ancient tradition while the West are innovators. In fact the opposite is true: the discipline of the Latin rite is more faithful to the practice and mind of the patristic Church, while the Eastern discipline today can be traced back only to the Quinisext Council, which represents a marked departure from earlier customs.

Quinisext canon 13 allows married priests and deacons to use their conjugal rights. It bases itself on the sixth Apostolic Canon and on the Codex canonum Ecclesiae Africae of Carthage. The invocation of the sixth Apostolic Canon is problematic, not only because the canons are entirely spurious, but because doing so involves one in a series of contradictions, as we have seen above. The canons of Carthage do not in any way support the conclusion of Quinisext. In fact, they say quite the opposite, and it is only by omitting the most relevant portions and inventing additional qualifications that the fathers of Quinisext were able to torture out the meaning they wanted.

A married, sexually active clergy is not the ancient Eastern custom. In an age when discipline was breaking down and heresy threatened the Church on all sides, the Easterners, fueled by a desire to flaunt their independence from Rome, adopted a novel position they thought would win them the loyalty of their beleaguered clergy while simultaneously snubbing the West. Knowing this position was pure novelty, they cloaked it in apostolicity by citing a spurious canon and misrepresenting the councils of Carthage, as well as by citing Scripture entirely out of context while concurrently ignoring all subsequent legislation throughout the centuries (both East and West) which inconveniently contradicted their narrative. They thus compromised with the lax morals of the time by placing their accommodated discipline in opposition to the universal tradition.

In concluding, it must be noted that when we discuss the issue of a married and sexually active priesthood, which Pope Sergius called “erroneous novelties,” we are not talking merely about what would become Eastern Orthodoxy. Eastern Catholics in union with Rome also have a married and sexually active priesthood and are in good standing with Rome, which respects the tradition of their churches. The point of this article is certainly not to say that Rome should try to impose its disciplines on the Eastern Catholic Churches at this point, nor is it to deny the tradition of married priests in Eastern Christianity. Rather, the point is that this is not an ancient, apostolic custom. It is a custom, yes, but one that dates from the 7th century and was grounded on a novelty—a compromise born out of an atmosphere of flagrant enmity with Rome. The point of this article is that Rome, not the Eastern Churches, preserves the apostolic custom.

Apologists of clerical celibacy are on firm ground when they assert that this was the discipline of the ancient Church. The patristic Church never accepted the idea of a sexually active priesthood, and the Quinisext Council in Trullo certainly does not represent apostolic teaching.

(1) Fr. Christian Cochini follows Joannou’s translation of the canons, in which the phrase “keep the rule of exact perfection” is rendered “follow the very severe discipline.” We cite the translation found in the Post-Nicene Fathers. We are not competent to examine the merits of each translation but merely note the difference.

(2) Leo the Great, Letter 167, Q. 3

(3) Andrew J. Ekonomou, Byzantine Rome and the Greek Popes (Lexington Books 2007 ISBN 978-0-73911977-8), p. 222

Phillip Campbell, “The Quinisext Council in Trullo and Priestly Celibacy,” Unam Sanctam Catholicam, Feb 23, 2015. Available online at https://unamsanctamcatholicam.com/2024/04/the-quinisext-council-in-trullo-and-priestly-celibacy