The origin of the Feast of All Saints dates to the late 4th century in the eastern Roman Empire. Syria, Pontus, and Constantinople all attest to feasts for the martyrs in common as early as 373; such a feast is attested in Constantinople in sermons of Chrysostom, in Pontus in the acts of St. Basil of Caesarea, and in Antioch during the time of St. Ephrem the Syrian (c. 370). The Chaldean Christians attest to the celebrations in Mesopotamia (modern Iraq) as early as 411.

After the 5th century, the growing number of saints and martyrs necessitated a single feast to commemorate them all in common. By this time, every local church seemed to have some feast for all the saints, though on various days; the Christians of Edessa observed it on May 13th, while the Syrians observed it on the Friday after Easter, with the exception of the ancient church of Antioch, where it was celebrated on the Sunday after Pentecost. St. Maximus of Turin (d. 465), too, appears to have preached on the theme of all martyrs on the Sunday after Pentecost. The oldest extant Roman lectionary, the Würzburg Lectionary (700), likewise assigns the Sunday after Pentecost to the “dominica in natale sanctorum”, that is, the Nativity of the Saints.

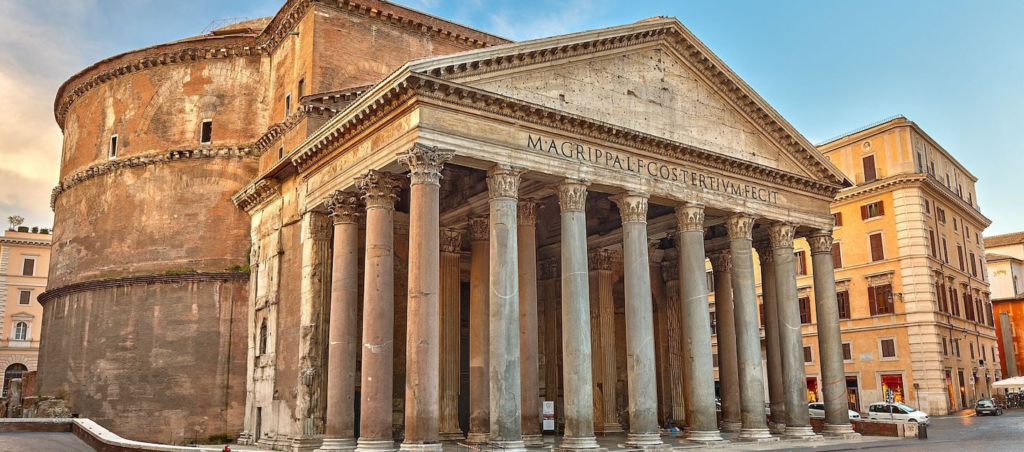

The year 609 was the pivotal moment in the history of All Saints, for it is ever connected with the re-dedication of the Pantheon in Rome as a Christian Church—the first example of an old pagan temple in Rome being repurposed for Christian worship. Many are unaware of the rich political and religious history behind the dedication of this building and the institution of the universal feast that would become so formative in the Christian west (and which would morph into Halloween in the modern times). We will first focus on the political background of the era and the events that culminated in the granting of the Roman Pantheon to the Catholic Church in the year 609 with its subsequent re-dedication as a place of worship dedicated to all the saints.

Political Background: Maurice and Phocas (582-610)

Ever since the death of Emperor Justinian in 565, the Byzantine Empire had been in a state of disarray. The Justinian dynasty ended in 569 with the death of the short-lived Justin II, who was succeeded by Tiberius, one of his commanders. This Tiberius, however, was dead by 582, perhaps by poison, and was in turn succeeded by one of his own generals, Maurice. The continuous political turnover destabilized the empire, which was already suffering from extensive wars against the Avars and Persians.

The new emperor Maurice was a capable administrator, but his reign was plagued by constant external threats. He made the fatal mistake of losing the esteem of the army due to his niggardly fiscal policy. To improve his finances, he cut wages in 588, which led to a mutiny on the Persian frontier. He lost the respect of the Danubian forces when he refused to pay a relatively small ransom to rescue 12,000 Byzantine hostages who had been taken prisoner by the Avars in the year 599. The military on the Danube even sent a delegation to Constantinople in 600 to protest and beg the Emperor Maurice to aid their comrades, but Maurice refused, and the Byzantine prisoners were subsequently executed.

One of the leaders of the Danubian delegation was a centurion called Phocas. Angered that Maurice had commanded the army to remain beyond the Danube for the winter, the Danubian soldiers mutinied and in 602 proclaimed Phocas their new emperor, elevating him on their shields. When the news reached Constantinople, riots broke out, forcing the unpopular Maurice to flee. Phocas marched into the city and was crowned emperor by the Patriarch on November 23rd, 602. Maurice and his sons would subsequently be captured and executed.

Phocas’s new position was precarious. The empire still suffered from multiple foreign threats; Phocas himself was not universally accepted in Constantinople and conspiracies constantly swirled about him, draining much of his attention and energy. Though still nominally under Byzantine control, Italy had been ignored under the reigns of Maurice and Tiberius. It subsequently suffered from constant invasions from the Lombards in the north. Pope St. Gregory the Great hoped to draw the new emperor’s attention to the plight of Italy. He sent Phocas a panegyric, hailing him a restorer of ancient Roman liberties, a pious and clement lord, and a friend of the Roman people. It was Gregory’s hope that the new emperor would send assistance to the suffering Italian peninsula.

Phocas was impressed with the pope’s praise and looked to Italy as a source of support for his flagging fortunes. He sent Pope Gregory portraits of himself and his wife, which were hung in the oratory of St. Caesarius in the imperial palace on the Palatine, with promise of more aid and assistance in the future. Phocas sent a statue of himself to Rome in 608, engraved with an imperial proclamation affirming the liberties of the Roman people. Incidentally, this monument of Phocas was the last official act of the imperial government to be posted in the Roman forum. Phocas sought to cultivate a friendly relationship with Pope Gregory, who had once served as apocrisiarius to Constantinople and had strong ties with the imperial court. (1)

Pope Gregory, however, died in 604. Following precedent, Phocas’s approval was sought for the confirmation of a successor to Gregory. After the brief pontificate of the unpopular Sabinian, Phocas confirmed the election of Pope Boniface III in 607. Like Gregory, Boniface III had served as apocrisiarius and in that capacity already enjoyed the confidence of Emperor Phocas. He managed to obtain a decree from Phocas which reaffirmed that “the See of Blessed Peter the Apostle should be the head of all the Churches.” (2) This ensured that the title of “Universal Bishop” belonged exclusively to the Bishop of Rome, and effectively ended the attempt by Patriarch Cyriacus of Constantinople to establish himself as “Universal Bishop.”

The Pantheon and the Church of All Saints

Despite the promising beginning to his pontificate, Boniface III died suddenly in September 607, less than nine months after his ascension. The new pope, Boniface IV, was consecrated in 608 after receiving confirmation of his office from Emperor Phocas.

By this time, Phocas was facing a revolt from his son-in-law Priscus, commander of the Excubitors, the Byzantine imperial guard. Priscus appealed to the general, Hercalius the Elder, to overthrow Phocas, who was widely regarded as a usurper. Hercalius the Elder and his son, also named Heraclius, launched their revolt by cutting off the grain shipments to Constantinople.

As the revolt was brewing, Pope Boniface petitioned Phocas to grant custody of the Roman Pantheon to the Roman Church. The Pantheon was a temple dedicated to all the gods of Rome that had been built during the reign of Emperor Hadrian (117-138) on the site of an earlier structure built by Marcus Agrippa during the Augustan age. The temple had been repaired during the reign of Septimius Severus (193-211) but by the time of Pope Boniface IV had fallen into disrepair. As a civic building, Emperor Phocas had the titular authority over the structure. He granted permission for Pope Boniface to convert it into a church.

The translation of the building to papal oversight was recorded by the historian John the Deacon, who wrote: “Another Pope, Boniface, asked the same [Emperor Phocas] to order that in the old temple called the Pantheon, after the pagan filth was removed, a church should be made, to the holy virgin Mary and all the martyrs, so that the commemoration of the saints would take place henceforth where not gods but demons were formerly worshipped.” (3) The restoration project was massive; relics were translated from the catacombs to be interred beneath the altar, twenty-eight cartloads of which were enclosed in a porphyry basin and buried within the altar enclosure. The newly restored church—now called the Church of St. Mary and All Martyrs—was dedicated on May 13th, 609.

The dedication of the church to all the martyrs was meant to coincide with the formalization of the solemnity of All Saints as a universal feast by Pope Boniface IV. Because of this, the date 609 is often incorrectly taken as the establishment of the Feast of All Saints. As we have seen, Boniface IV was not instituting a new feast. Rather, he ordered the commemoration already being celebrated all over the Christian world to be fixed on May 13th as the Feast of the dedicatio Sanctae Mariae ad Martyres, the day the Pantheon was rededicated as a Christian Church.

The date of the feast would later be moved to November 1 by Gregory III (731-741), who did so at the time of the dedication of a new chapel within St. Peter’s to hold the relics of several martyrs and confessors. But 609 and the pontificate of St. Boniface IV will always be remembered as the time of the formal institution of the universal commemoration.

As for Emperor Phocas, he did not come to so fortunate an end. The Heraclid family succeeded in capturing Constantinople and Phocas was swiftly executed on October 5th, 610. Heraclius the Younger was proclaimed emperor in his stead.

The Pantheon restoration of Boniface IV was unfortunately short lived. The Lombard historian Paul the Deacon records that the Church of St. Mary and All the Martyrs was despoiled by the Byzantine Emperor Constans II in 663, only 54 years after its dedication. He says:

Remaining at Rome twelve days [Constans] pulled down everything that In ancient times had been made of metal for the ornament of the city, to such an extent that he even stripped off the roof of the church [of the blessed Mary], which at one time was called the Pantheon, and had been founded in honour of all the gods and was now by the consent of the former rulers the place of all the martyrs; and he took away from there the bronze tiles and sent them with all the other ornaments to Constantinople. (4)

The church would nevertheless be restored and enriched many more times throughout its long history. As for Pope Boniface IV, he later converted his own house into a monastery, where he retired and died in 615. He has ever been venerated as a saint in the western Church, forever associated with the establishing the Feast of All Saints throughout the Roman rite.

The preceding article is taken from Chapter 10 of the book Feasts of Christendom: History, Theology, and Customs of the Principal Feasts of the Catholic Church by Phillip Campbell.

Related: Is Halloween of Pagan Origin?

(1) The apocrisiarius was essentially an ambassador from the Holy See to the imperial court at Constantinople.

(2) T. Oestereich, “Pope Boniface III”, in The Catholic Encyclopedia (New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1907). Retrieved February 21, 2021 from New Advent: http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/02660b.htm

(3) John the Deacon, Monumenta Germaniae Historia (1848 English edition) 7.8.20

(4) Paul the Deacon’s History of the Lombards, Book 5, chapters 11-13 (PL95, cols 602 and 604)

Phillip Campbell, “The Feast of All Saints and the Roman Pantheon,” Unam Sanctam Catholicam, October 31, 2018. Available online at https://unamsanctamcatholicam.com/2022/10/the-feast-of-all-saints-and-the-roman-pantheon