The most distinguishing feature of the Palm Sunday liturgy, whether modern or ancient, is of course the blessing, distribution and procession with palms, from whence the common name of the feast is derived. However, this is not the only distinctive feature of the Mass; it is also noteworthy for the reading of the Passion narrative in multiple voices. This is recalled in the Roman Rite, where the current official name for this feast is Palm Sunday of the Passion of Our Lord. The ancient Gelasian Sacramentary (c. 750) makes no mention of a procession with palms but simply calls the feast Dominica in palmis, De passione Domini; many other names, ancient and modern, make reference to Jesus’ passion. The reading of the Passion narrative on this day is very ancient. In this article we will trace the history of this practice, focusing in on the use of different lectors to represent the different voices in the Gospel narrative.

The history of what readings are done on a particular day is best discerned by studying lectionaries, the compilations of Scripture readings assigned for worship on a given occasion. The earliest extant lectionary of the Roman rite comes from the Meroginvian era Capitulary of Wurzburg (c. 700). In this document, the passion narrative according to St. Matthew (26:1-27:66) is assigned for Palm Sunday. (1) The Capitulary of Wurzburg makes no mention of the division of the recitation among different speakers. We can’t infer too much from this, however; ancient lectionaries often denote only what readings are assigned to a particular day and didn’t always include the specific texts themselves.

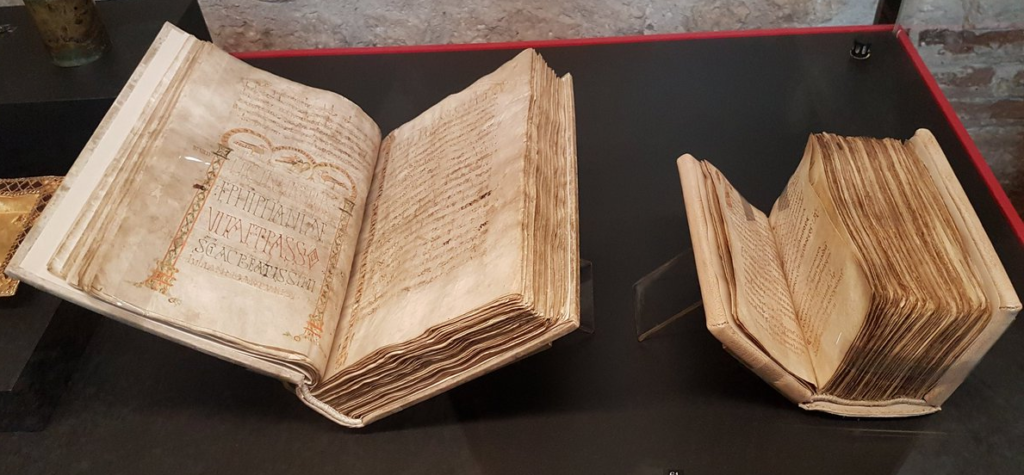

For this, we would need to look to the ancient missals. In the late-Merovingian Bobbio Missal (c. 650) we see an interesting development towards the practice of multiple voices. In the Bobbio Missal we see the narrative of the Lord’s Passion annotated with special markings along the margin to distinguish the words of our Lord. A century later similar markings are found in the margins of a missal from Durham, England. This does not mean we are to multiple readers, yet; the markings probably set off the words of our Lord in such a way that the deacon reading the text would use different pitches or volume to distinguish the words of Christ from those of Pilate, the crowd, etc.

This is inferred by a reference from the thirteenth century bishop Durandus of Metz who speaks of a division of voices according to pitch but without mentioning different lectors. It thus seems that, at least from 750 to 1254, the practice was to have a single deacon read the Passion narrative utilizing different voices for Christ and the others.

We mention 1254 because it is in this year we see the first explicit reference to the distribution of voices in the narrative amongst many readers. This is in the Dominican liturgical document, the Gros Livre. A similar reference is made in the Sarum Gradual of 1300, of the old Sarum Rite, which designates five cantors for the Passion plus a sixth special cantor to chant the words of our Lord. Note that the first known uses of multiple singers came not from the Roman rite proper, but from derivative rites (the Dominican and Sarum rites). This would explain why the practice is not seen in the Roman rite proper until much later.

While the practice of multiple readers was spreading in England and France, in Rome itself a single deacon was still reading the entire Passion narrative as late as the 1450s; in a missal of 1530, three different voices are denoted for the reading of the Passion (tenor, alto, bass), but there is no explicit mention of different cantors. It is only in the 1600 edition of the Caeremoniale Episcoporum and an early decree of the Congregation of Sacred Rites (1612) that the Roman rite speaks of three different cantors -all deacons – for the different voices.

These documents are interesting because they denote not only the division of voices, but specify what pitch each voice was to be sung in. The first deacon assumed the role of narrator and chanted the words of the evangelist in a tenor voice. The words of Christ were sung in a deep bass voice by a second deacon. The third deacon takes all the other parts and is to use a higher, contralto voice. This custom, with very minor changes, is still observed in celebrations of the Extraordinary Form.

In the late Middle Ages, the custom was further introduced of observing a pause or genuflection at the moment Christ’s death is narrated. In the 1300s, a missal from Westminster, England, admonishes the priest to pronounce the words emisit spiritum (“gave up the ghost,” Matt. 27:50) with especial devotion. A Roman ordinary from the early 1400s calls for a pause and a genuflection at the emisit spiritum. This was prescribed for the Good Friday Passion narratives, as well.

To sum up: the practice of reading the Passion of St. Matthew on Palm Sunday goes back as far as we have documentary evidence. By the Carolingian era, the deacon chanting the Gospel was using a different pitch or “voice” to set off the words of Christ in the reading. This remained the norm in the Roman rite for many centuries whilst in the derivatives of the Roman rite, especially the Sarum and Dominican usages, the practice of dividing up the parts among different cantors originated. This practice spread in England and France throughout the latter Middle Ages, while the Diocese of Rome, always conservative in liturgical matters, did not adopt the practice until much later, sometime between 1530 and 1600. Following the suppression of various local usages in the post-Tridentine period, the practice of using multiple readers became the norm throughout the Latin rite by 1612.

Only one question remains: The various missals and ordinaries all stipulated that the readings were to be done by deacons—sometimes three, sometimes five or six, but always by deacons. From whence, then, do we get the practice, now so common, of the tripartite division between a lay lector, the priest, and the congregation? This practice is a relative novelty, introduced on March 25, 1965 with the document Plures locorum, which granted permission for the laity to begin taking these parts. It thus originated from that bizarre period 1965-1969, before the promulgation of the Novus Ordo but after the door had been opened by Vatican II for liturgical tinkering.

Much of the information found in this article was found in the wonderful liturgical compendium The Week of Salvation: History and Traditions of Holy Week by James Monti.

(1) It is noteworthy that the exclusive use of St. Matthew’s passion was a common feature of the Roman Rite until the promulgation of the Novus Ordo, which uses a three year cycle of the passion accounts of Mark, Luke and Matthew.

Phillip Campbell, “A History of Multiple Voices in the Passion Readings,” Unam Sanctam Catholicam, April 12, 2014. Available online at https://www.unamsanctamcatholicam.com/2023/04/a-history-of-multiple-voices-in-the-passion-readings/