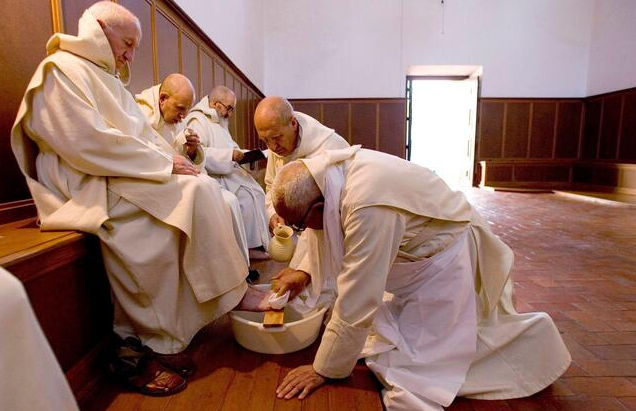

The Holy Thursday Mass of the Lord’s Supper is distinctive for the foot washing ceremony known as the Mandatum. The ceremony is well attested in the history of the East and the West and serves to highlight the Mass of the Lord’s Supper as the opening of the Triduum, the “Still Days” preceding the celebration of our Blessed Lord’s Resurrection on Easter. The washing of the feet has its origin in the actions of our Lord after the Last Supper, as narrated in the Gospel of St. John. It later became a sign of service in the early Christian community and eventually found its way into the liturgies of Holy Thursday.

The origin of the rite is found in the Gospel of John 13:1-7, immediately after the Last Supper. Jesus pours water over the disciples’ feet and begins to wash them, saying that the act was an example that those called to fill the high places in the Church must be willing to serve (John 13:15). He not only washes their feet, but also commands them to follow His example.

Why did Jesus command this? Textually, the intention of our Lord seems to be general; that is, He is not commanding foot washing in particular but service and humility in general. Nevertheless, from the latter patristic era we see that the rite of foot washing was practiced on Holy Thursday as a sign of apostolic service. Though foot washing on Holy Thursday was not attested until the late patristic age, the practice seems to have been observed by Christians in a more general way much earlier. St. Paul mentions foot washing as a characteristic act of piety in the apostolic Church (cf. 1 Tim. 5:10). There are further references to foot washing in general in Tertullian, Ambrose and elsewhere, though not in direct connection with Holy Thursday.

The name Mandatum comes from the Latin mandatus, “to commission or mandate”; the English “Maundy Thursday” comes from a corruption of mandatum, in the context of John 13:34, “A new commandment (mandatum) I give you”, which by the Middle Ages was part of the traditional readings for Holy Thursday.

The earliest records of a special Mass commemorating the Last Supper is in the diary of the pilgrim Egeria, who visited the Jerusalem for Easter sometime around 381-384. Egeria mentions that Mass was offered twice, once in the morning and once in early evening, around 4:00 PM. The people are dismissed after the 4:00 PM Mass but bidden to return to church at 7:00 PM for a vigil. She tells us:

On the fifth weekday everything that is customary is done from the first cockcrow until morning at the Anastasis, and also at the third and at the sixth hours. But at the eighth hour all the people gather together at the martyrium according to custom, only earlier than on other days, because the dismissal must be made sooner. Then, when the people are gathered together, all that should be done is done, and the oblation is made on that day at the martyrium, the dismissal taking place about the tenth hour. But before the dismissal is made there, the archdeacon raises his voice and says: “Let us all assemble at the first hour of the night in the church which is in Eleona, for great toil awaits us to-day, in this very night.” Then, after the dismissal at the martyrium, they arrive behind the Cross, where only one hymn is said and prayer is made, and the bishop offers the oblation there, and all communicate. Nor is the oblation ever offered behind the Cross on any day throughout the year, except on this one day. And after the dismissal there they go to the Anastasis, where prayer is made, the catechumens and the faithful are blessed according to custom, and the dismissal is made.” (1)

About fifteen years later, St. Augustine mentions the Mass of the Lord’s Supper in his first letter to Januarius. In that epistle, Augustine relates that in regions where Christians were more numerous it had become custom to celebrate two Masses on Holy Thursday, “both morning and evening, on the Thursday of the last week in Lent”, while in places where Christians were fewer only one Mass was held on Holy Thursday. (2) In that same letter, Augustine notes that of the two Masses offered that day, the evening Mass seemed to be the more important, connecting its offering with the words of the Scripture, “Likewise, after supper” (Luke 22:20) which affirms the Last Supper was held in the evening. (3)

By the 7th century, the west seems to have been celebrating three Masses on Holy Thursday, according to the Gelasian Sacramentary and the Gregorian Sacramentary, both dating from the 700’s. It is during this period that we have the first positive attestation of the Mandatum ceremony within the Holy Thursday Mass proper, which we shall now examine.

The Mandatum

The introduction of the Mandatum is reflected in the readings for the Holy Thursday Mass. The Armenian Lectionary, believed to be a compilation of prayers used in Jerusalem in the late 5th century, lists the readings for this Mass as 1 Cor. 11:23-32 and Matt. 26:17-30, both accounts describing the institution of the Eucharist. But by the time we get to the oldest Latin rite lectionary, the late Merovingian Capitulary of Wurzburg, the Gospel reading from Matthew has been replaced by John 13:1-15, the narration of Christ washing the disciples’ feet. The institution narrative from 1 Corinthians and the foot washing narrative of John 13 have remained paired in the Latin rite ever since.

It is reasonable to assume that the Mandatum entered the Holy Thursday Mass between the Armenian Sacramentary (c. 450) and the Capitulary of Wurzburg (c. 675), as reflected in the replacement of St. Matthew’s Gospel for St. John’s Gospel. The first unambiguous reference to the foot washing ceremony comes from a 7th century document called “Roman Ordo in Coena Domini” which mentions the pope washing the feet of his attendants on Holy Thursday.

The Ordo dates from the late 7th century. We should not, however, presume that the institution of the rite itself is that late. In fact, there is evidence that it may be somewhat older. In 694, the Visigothic King Egica summoned the seventeenth regional Council of Toledo. The Council promulgated eight canons, among which we read the following:

The washing of feet at the feast of the Coena Domini, which has fallen into disuse in some places, must be observed everywhere. (4)

The Council noted that the practice of foot washing had been abandoned “partly from slackness, partly from custom” and lamented that “in sundry churches the priests no longer wash the feet of the brethren in Coena Domini”. (5) If the Mandatum had already “fallen into disuse” in 694, it is clearly implied that the tradition was much older. This is verified by the appearance of the Mandatum in a Spanish document called the Liber Ordinum, which is a compilation of Spanish liturgical practices from the 5th-7th centuries. It also appears in several other similar compilations, all containing rites from the 5th-7th centuries. Thus, the practice could date back to the late Western Roman Empire.

It is this author’s opinion that the Mandatum arose in the West in the early 6th century in connection to the spread of Benedictine monasticism. The Rule of St. Benedict, composed in 529, prescribed foot washing by the abbot as a sign of humility. The Catholic Encyclopedia notes:

The Rule of St. Benedict directs that it should be performed every Saturday for all the community by him who exercised the office of cook for the week; while it was also enjoined that the abbot and the brethren were to wash the feet of those who were received as guests. The act was a religious one and was to be accompanied by prayers and psalmody, “for in our guests Christ Himself is honoured and receive”. (6)

With the increasing prevalence of Benedictine bishops in the 6th century (such as St. Augustine of Canterbury and even Pope St. Gregory the Great, to take the most notable), it is probable that the Benedictine practice crossed over into the usage of the secular clergy. It gradually spread throughout the west from 529, being observed with greater or lesser regularity in various regions—including Rome—until by 700 it was a fairly universal tradition, such that the fathers of Toledo could lament its disuse. But this is only a theory.

After the 8th century, details about the rite are more abundant. It is described in monastic documents from 10th century England, for example. Of particular interest is the Constitutions of Lanfranc of Canterbury. Lanfranc (d. 1089) was a retainer of William the Conqueror and became Archbishop of Canterbury after the deposition of Stigand, the last Anglo-Saxon to hold the office. As one of the most important ecclesiastics of the day and mentor of St. Anselm, Lanfranc’s Constitutions were meant to bring the practices of the English Church in line with those of the Norman Benedictine monasteries, which had been influenced by the Cluniac reform, of which William the Conqueror was an enthusiastic proponent.

The Constitutions describe how at an appointed time during the Holy Thursday Mass, a chosen group of poor men would be led into the cloister of the monastery and seated in a row. The monks would then enter, each one taking an assigned place before one of the poor men (the abbot was assigned two poor men). The prior would then strike a board three times, and all the monks would genuflect before the poor, adoring the presence of Christ in them. The monks then washed their feet, kissed them, and dried them with a towel. After this they bowed and touched their forehead to the feet of the poor. The poor were then served beverages by the monks and given two pence each, after which the service concluded with a prayer by the abbot.

Interestingly enough, the Benedictine Mandatum did not end there. After the departure of the poor, the brothers would gather in the chapter house for a second foot washing ceremony among themselves. The abbot and prior, girt with linen cloths, took to their knees to wash, dry, and kiss the feet of the monks. The abbot and prior then would take turns washing each other’s feet.

The double Mandatum does not seem to have been confined to Benedictine monasteries of the Cluniac usage. The pontifical Mass of the Lord’s Supper as celebrated in Rome in the 12th century also featured two foot washings: one in which the pope washed the feet of his subdeacons in public, and another private Mandatum in which the pope washed the feet of thirteen poor men in his apartments. This “Mandatum of the poor” seems to have existed alongside the clerical Mandatum in monasteries and in Rome from the 11th century until the 14th century. By the 15th century, the “Mandatum of the poor” had disappeared from the Roman pontifical liturgy. The Ceremoniale Episcoporum of 1600, however, contains an allusion to the old Mandatum of the poor by allowing that either thirteen paupers or thirteen clerics be selected for liturgical foot washing.

It is also noteworthy that by the 11th century, when the “Mandatum of the poor” and the clerical Mandatum were being celebrated side-by-side, the various daily Masses on Holy Thursday were reduced to a single Mass offered in the morning. Recalling the preeminence of the evening Mass in the early Church and Egeria’s description of the different devotions at the various Masses, it is possible that the existence of the double Mandatum from the 11th century onward can be explained as a combination of two different ceremonies which used to occur at separate Masses prior to the elimination of the evening Mass in the 11th century. This is mere conjecture, however.

References to the Mandatum at the parish level are rare. We saw it mentioned in 694 at the Seventeenth Council of Toledo, but as that was an episcopal synod, we do not know whether the reference was to parish Masses or merely pontifical Masses. We do know foot washing at the parish level must have occurred in the 16th century because Martin Luther railed against it. In one of his Easter sermons, Luther said, “When it comes to theatrical foot washing, that is sheer ostentation.” (7) His sermons were delivered to average German laymen, which presupposes a common knowledge of the practice in most parishes.

It seems that the Mandatum was practiced regularly at the parish level from the late Middle Ages until the 18th century, at which time it begins to die out. The practice continued in various locations into the 19th century, but by then was considered a rarity. In Tasco, Mexico, a record from 1868 notes the Mandatum being performed in a parish on twelve poor men. The men were seated in the church dressed as the Apostles and wreathed in leaves. Their feet were then washed and kissed by the parish priest and vicar, followed by a dozen prominent men of the town who performed the same act. This took place immediately before the sermon.

By 1900, the practice at the parish level had apparently died out universally. It was not reintroduced until the 1955 “restoration” of Holy Week by the Sacred Congregation of Rites, which gave us the Mandatum practice as we know it today.

A particularly fascinating aspect of the Mandatum is its appropriation by secular rulers. Foot washing in imitation of Christ was meant as a sign of humility, a reminder to the Christian that he is called to serve. Throughout the centuries, the liturgical practice of the Mandatum inspired several imitations of the rite in the secular courts of Christian kings. Like the bishop or the pope, the Christian king, too, was called to use his high station to serve and consequently found great meaning in an adaptation of the Mandatum to his own office.

Examples of this are numerous. One of the more striking occasions of a royal foot washing comes from the reign of King Robert II of France (r. 996-1031), who once washed the feet of 160 members of the clergy on Holy Thursday. It was common in the Middle Ages for Christian kings to wash the feet of the poor once per year and then invite them to dine, sometime serving them at table. St. Elizabeth of Hungary (d. 1231) regularly chose twelve lepers for this service.

A particularly beautiful adaptation of the Mandatum was observed in the royal court of Spain. The following description of the Spanish royal foot washing of Holy Week in 1885 is taken from James Monti’s The Week of Salvation:

Following Mass at the Chapel Royal, the king and queen would proceed to the Hall of Columns. Arriving there at two o’clock in the afternoon, the king (Alfonso XII) entered in full ceremonial uniform, decked with all his medals of state, together with his queen (Maria Christina), who was dressed in a fine down and flowing train, with a white mantilla and a diamond diadem on her head.

In the center of the hall stood two platforms; on one twelve poor elderly men were seated, clothed in new suits provided by the king; on the other platform were twelve elderly women, likewise dressed in new clothing provided by the queen. Nearby stood an altar on which was placed a crucifix and two lighted candles. The bishop, who was Patriarch of the Indies, then went before this altar and read St. John’s gospel account of Christ washing the feet of His disciples at the Last Supper.

Following the reading, a small gold-fringed embroidered band was tied around the king’s waist, symbolizing the towel that Christ tied around His waist on this occasion. The king now mounted the first platform, accompanied by his steward, who brought a golden basin and ewer [jug]. He then knelt down before each of the men seated there and poured water over their feet, wiped them, and kissed them.

Likewise the queen performed this service on her knees for the poor women. Some years earlier, as Queen Isabella II (r. 1833-1868) was washing the feet of one woman, a beautiful diamond bracelet she was wearing fell from her arms into the basin. The other woman reached down and took it out of the water to return it to the queen, but the monarch handed it back to her, saying: “Keep it, hija mia; it is your luck.”

Upon completing the Mandatum, the king would lead the twelve elderly men down from the platform to a long table prepared for them where, after they had taken their places, the king set before each of them a sumptuous fifteen-course fish dinner, plus fifteen entremets [small cakes] and a flagon of wine. Similarly, the queen led the poor women to a second table, where she served them in the same manner. The food, together with all the flatware, glasses, and utensils with which it was served, was then packed into twenty-four large baskets, so that these poor people could take the rich banquet home with them. In addition, each was given a purse containing twelve gold pieces. (8)

This article is an excerpt from The Feasts of Christendom: History, Theology, and Customs of the Principal Feasts of the Catholic Church by Phillip Campbell (Cruachan Hill Press, 2021)

(1) The Diary of Egeria is available online at http://www.ccel.org/m/mcclure/

etheria/etheria.htm

(2) St. Augustine to Januarius, Epistle 54:4

(3) Ibid., 5-6

(4) Seventeenth Council of Toledo, Can. III

(5) Cited in James Monti, The Week of Salvation (Our Sunday Visitor: Huntington, IN., 1993), 110

(6) Thurston, Herbert. “Washing of Feet and Hands.” The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 15. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1912. 22 Mar. 2015<http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/15557b.htm>

(7)Martin Luther’s Easter Book, ed. Roland H. Bainton (Ausburg Books, 1997), 57

(8)Monti, The Week of Salvation, 115-116

Phillip Campbell, “Liturgical History of the Mandatum,” Unam Sanctam Catholicam, March 22, 2015. Available online at https://unamsanctamcatholicam.com/2023/04/liturgical-history-of-the-mandatum