It is well attested that the liturgical reformers of the Second Vatican Council argued in favor of Mass celebrated facing the people (versus populum) based on an appeal to historical Roman tradition. While the universal custom of the patristic era was to construct churches with the altars facing east and the people and priest worshiping together ad orientam, it was pointed out that there were several very important Roman basilicas that were actually constructed with the altar facing west. In such cases, the priest, facing west, would have faced the people, who would still have been oriented to the east. This was put forth as evidence of an ancient Roman custom of versus populum liturgies and hence gave support to the liturgical reformers who sought to push Mass “facing the people” in the Novus Ordo.

Subsequent studies have shown this argument to be flawed in several aspects. For one thing, it as since become clear that the orientation of these early Roman basilicas had much more to do with the particular topographical limitations of the sites than any supposed Roman “custom” as versus populum worship. It has also been demonstrated, most masterfully by Msgr. Klaus Gamber in Reform of the Roman Liturgy, that in such basilicas the priest did not ‘face the congregation’; rather, at the Eucharistic liturgy, the whole congregation turned themselves towards the doors of the basilica, forming a kind of arch with the priest at the center, but at any rate with everybody basically oriented the same way.

Furthermore, even if the assertion that the ancient Roman Church did occasionally practice versus populum, worship, it would not constitute an argument in favor of the practice in the 20th century. To argue otherwise implies a sort of archaeologist or antiquarian assumption, which is the belief that the Church of today ought to revert to the stage of development proper to the Early Church.

But let us return to the initial historical matter, namely, the fact that several very important Roman basilicas are not oriented toward the east, despite the universal ancient practice. The reason for this orientation has to do with topography or geography – but what about them? What is it about the lay of the land that necessitated placing an altar facing west instead of east? While the geographical-topographical explanation is well-known, many people are unaware of why these factors play a part in determining the orientation of the old Roman basilicas. The surprising answer is that it has to do with the cult of the martyrs.

In the earliest days of Christianity, Christians were entombed in privately owned cemeteries, usually in subterranean crypts. As these crypts expanded over time, the Christians continued to dig them down and out and they became the famous Roman catacombs. Tombs of martyrs were especially noteworthy and were the site of private pilgrimages and liturgical celebrations.

Beginning in the late 3rd century, Christians began openly building spaces for worship. Though this trend was interrupted by the Great Persecution (303-313), after the Edict of Milan (313) more and more Christian churches were built throughout the empire. Because of the great veneration in which the early Church held the martyrs, the most ideal locations for churches were near or, if possible, atop the subterranean tombs of the martyrs. Churches that could be constructed in such a way were usually built so that the altar was directly over the tomb.

The rationale for this was that the martyr, who stood before the throne of God, could add his or her prayers to the prayers of the Mass. This of course calls to mind the imagery of Revelation, where the souls of the martyrs are said to reside “under the altar”, from where they make constant intercession (Rev. 6:9-11). So ancient is the Christian cult of the martyrs that it is uncertain whether the practice of building altars over the tombs was inspired by Revelation 6 or whether Revelation 6 was describing a practice already in existence at the end of the first century.

At any rate, throughout the 4th century churches and basilicas were constantly being constructed atop the tombs of the martyrs. However, the new constructions posed a problem. Prior to the 4th century, Christians were accustomed to visiting the actual tombs of the martyrs, usually to pray but often to touch objects to them, which they then carried away as relics. Would not the construction of massive basilicas atop the tombs interfere with the direct access to the tombs which the laity were accustomed to having?

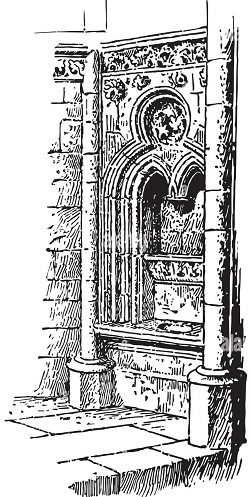

The early church builders solved this problem by the construction of small tunnels from the tomb up to the church. These tunnels, called cataracta, allowed the faithful to lower objects down on string or rope and touch them to the tomb. At the top, these cataracta spread up into a larger opening called a fenestella, which allowed larger groups of the faithful to gather around and access the cataracta at one time. Those familiar with Latin or even German will recognize the etymology of fenestella and that it was a type of small window.

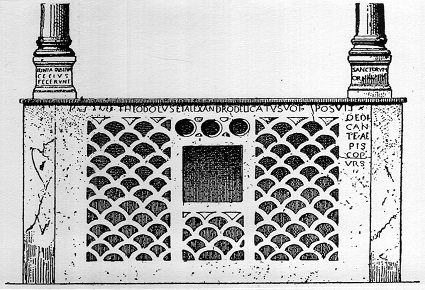

While this allowed the faithful some access to the tomb, it was not ideal. A more sought after arrangement was to build the tomb not directly on top of the tomb but around it. Such an arrangement can be seen in the basilica of Sts. Alexander, Eventius and Theodolus on the Via Nomentana in Rome. In this church, the area around the tombs was cleared away so the altar could be built around the tomb. The faithful were able to reach through the fenestella and actually place objects directly on the slab of the tomb.

In the construction of the churches, the fenestellae and the altar arrangements, we see considerations of liturgy and personal piety come into conflict. According to an almost universal custom of the day, liturgical sensibility demanded that altars be oriented towards the east, as we witness in most other cities in the 4th century. Yet personal devotions to the martyrs demanded that the faithful have some kind of direct access to the tombs. It was certainly possible to accommodate both requirements at times, but in many cases both demands could not be met and the early church builders had to choose to prioritize one custom over the other.

In the cases of the Roman basilicas built over the tombs of some of the most famous martyrs of the ancient Church—deference was always given to the practice of accessing the martyrs tombs. In many cases, such as the church of Sts. Alexander, Eventius and Theodolus, the location of the fenestella dictated the location and orientation of the altar. If the site of the tomb and the fenestella through which the tomb were accessed made an eastward facing altar impractical, the altar was oriented any way necessary in order to maintain free access to the fenestella. Thus the faithful could have free access to the fenestella during the divine service. The importance of maintaining this access explains why some Roman churches were constructed with the altar facing the people.

For example, a tomb located centrally in a broad, flat cemetery would not prove problematic. But if a tomb was located towards the edge of a cemetery, or near a precipice, or a long a major thoroughfare, then constructing an ad orientam basilica over it was often impossible. A classic example is St. Paul Outside the Walls, which was built on an awkward triangular piece of land with a steep decline abutting the Tiber immediately to the west. In such circumstances, if the altar was facing east, it was sometimes necessary for the priest to stand behind it in order to maintain the right orientation; at other times the altar itself was constructed facing west. It depended upon the topography of the land, which, as we have seen, is clearly connected to the location of the martyr tombs.

A further confirmation of this theory is the fact that, of all the Roman basilicas, the cemterial basilicas and only the cemeterial basilicas, was the altar so placed as to face the priest to the people. It can be said without too much exaggeration that in the cemeterial basilicas the sacrifice of the Mass was more of an occasion to visit the tomb of the martyr.

Thus, the purpose in such versus populum orientation was never anything other than a practical problem arising from the location of the fenestellae in the cemeterial basilicas. It certainly offers no justification for the widespread use of versus populum orientation in the Novus Ordo Mass today.

Phillip Campbell, “What is a Fenestella?” Unam Sanctam Catholicam, September 21, 2014. Available online at http://unamsanctamcatholicam.com/2022/05/what-is-a-fenestella