It sometimes happens in the history of the Church that when doctrine and spirituality become skewered by errant teachings, or when catechesis is incomplete, bizarre practices start to pop up. As a modern example, we could cite the practice in the Philippines of crucifying live individuals during Holy Week. Sometimes these practices are alleged to be supernatural in origin or demonstration of God’s affirmation of a movement or spiritual leader. In these cases, what passes for piety or a miraculous sign from God are really nothing other than the results of poor catechesis, disobedience, or an overactive imagination.

A similar occurrence happened in Paris around 1730 in what must rank as one of the most bizarre movements in the Church’s history—the Convulsionaries. It is not accurate to call the Convulsionaries heretics, although they were loosely connected with the Jansenists of Port-Royal; rather, their movement should be seen as an example of bizarre, misguided piety, much like the Flagellants of the 14th century. The origin of the Convulsionary movement is the cemetery of St. Medard in Paris, where a certain deacon (who was a fanatic and sympathizer with the Jansenists) was buried. Soon after the deacon’s burial, a girl claimed to have been cured of blindness. Archbishop Vintemille of Paris examined the “miracle” and found it a complete hoax, which he asserted the Jansenists were propagating as a means of giving divine sanction to their doctrines.

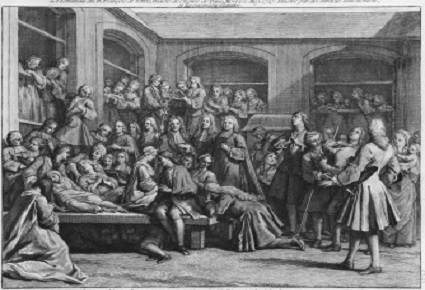

Nevertheless, despite the bishop’s condemnation of the miracle, multitudes began seeking out the tomb in hopes of being healed. More miracles were reported, but they were not miracles in the way we are used to thinking of them; in fact, we would say they were not miracles at all, but hallucinations or worse. Consider the example of the Abbé Bisherand, a man who was born with one leg much shorter than the other. In hopes of being cured, he prostrated himself on the tomb and laid there for quite some time. His leg did not lengthen, but he insisted that he felt a sensible elongation of his leg, even though there was no physical healing. He claimed that the leg was in fact healed, and that it felt healed, but that this healing was invisible to others. This “sensible” elongation was touted as miraculous, and visits to the St. Medard graveyard increased. Other persons began laying on the tomb and experiencing violent convulsions (from whence they were called Convulsionaries); some were reportedly levitated while convulsing. Most of those who experienced these convulsions were females, and we are told that their contortions and agility were astonishing, and often indecent.

This phenomenon became the talk of Paris; the streets to the cemetery were constantly crowded and the press of Paris published articles either for or against the Convulsionaries. The Archbishop of Paris thought the matter so serious that he published a long pastoral letter warning the faithful against it, but to no effect. Finally, King Louis XV ordered the graveyard closed, the entryways blocked up and the roads leading to it guarded by soldiers. This did not halt the Convulsionary movement, however. Persons sneaked into the graveyard and removed dirt from the deacon’s tomb, and persons laying on the particles of dirt experienced the same contortions and alleged miracles. Regarding these “miracles”, they began to look less and less like anything miraculous and more like some circus freakshow – people, without harm, swallowing stones, knives, or eating fire; some, like in the Philippines, crucifying themselves and alleging no pain; many Convulsionaries voluntarily underwent many other tortures, all while exhibiting the most serene expressions and claiming they felt no pain. This went on for almost thirty years until it died out in the 1760’s. Some of these accounts survive in the writings of Friedrich Melchior, Baron von Grimm, who wrote of the Convulsionary sect in his famous Correspondance littéraire. He writes of the crucifixion of two “sisters” of the sect:

“The first scene was that of the crucifixion of the sister Rachel and the sister Felicité, two women from thirty to forty years in age, who were moved, as they pretended, to exhibit this lively image of the passion of our Saviour in a mean lodging in Paris in August, 1759. These two wretched creatures were actually nailed to two wooden crosses, through their hands and their feet, and continued fastened to them for upwards of three hours; during this time they sometimes pretended to slumber, in a beatific trance, and, at other times, uttered a quantity of infantine nonsense and gibberish, asking for sweetmeats, and threatening and fondling the spectators, in lisping accents, and all the babyish diminutives of the nursery. The nails were, at length, drawn out, and a considerable quantity of blood flowed from all the wounds; after washing and bandaging which, the patients sat down quietly to a little repast in the midst of the apartment. Although their votaries and ghostly advisers maintained that they experienced no pain, but on the contrary, the most exquisite delight from these operations, the respectable reporters concur in testifying that it was easy to see throughout that they were in the utmost agony…After this tragedy, there was another kind of afterpiece by the inferior performers and pupils of this school of imposture: various women were stretched on the floor and beat with bludgeons on the head and breast, and trodden violently under the feet of their spiritual assistants, to their infinite relief and gratification, as the managers o the spectacle most solemnly asserted, but, with more or less apparent dread and suffering…They had also the points of swords forcibly thrust against their sides and bosoms…

The second exhibition…consisted in the crucifixion of the sister Francoise and the sister Marie, -and a great deal of beating and thrusting with swords on the bodies of some of their unfortunate apprentices…Francoise remained upwards of three hours on the cross; which was shifted into a great variety of postures during this period: but the sister Marie wanted faith or fortitude to edify the beholders to the same extent – she shuddered at the fastening of the nails, and, in less than an hour, fairly cried out that she could stand it no longer, and must be taken down: she was unfastened accordingly and carried out of the chamber in a state of insensibility, to the no small discomfiture of her associates.

The spectacle was concluded with a still more unlucky performance. The sister Francoise had announced that god had commanded her on that day to burn the gown off her back, and had assured her of much comfort from the operation. After a great deal of grimacing accordingly, fire was actually set to her skirts but, instead of appearing to experience any delight, the failing saint very speedily screamed out in terror and they were obliged to pour water upon her petticoats and carry her off half roasted – half drowned – and utterly ashamed of her exhibition.

Those horrible and degrading practices had been going on in the heart of Paris for upwards of twenty years…a few profligate priests were supposed to be at the bottom of the contrivance, but all the agents, or victims, rather, were women” (1)

All citations from The Church in France by Charles Butler, Clarke & Sons, London, 1817, pp. 132-142).

Phillip Campbell, “Convulsionaries (1759)”, Unam Sanctam Catholicam, November 29, 2011. Available online at http://unamsanctamcatholicam.com/2022/05/19/convulsionaries-1759