Secular accounts of the spread of Christianity in the Roman Empire tend to present the growth of the Church in purely natural terms, a function of factors sociological, economic, and political. A closer look at these explanations, however, reveals that they are insufficient to account for the growth of Christianity.

The Poor, Women, and Roman Roads

For example, it is stated that Christianity achieved popularity among the lower classes because of its embrace of the poor. I am uncertain where the idea that pagan religions “didn’t accept the poor” came from; for sure the poorer Romans wouldn’t have had a chance of being initiated into the Elusinian Mysteries or of becoming Vestal Virgins, just the Church of Scientology today is restricted to the rich socialites. But Roman religion was syncretist and practical, and thus had gods and rituals for every walk of life. The poor were not neglected by pagan religion—in fact, as we learn from the accounts in the life of St. Benedict, it was the rural poor who clung to paganism the longest. The poor had access to religion in paganism, even if it was only the vulgar cult of Priapus. Christianity certainly offered more to the poor by way of charity and egalitarian acceptance into the Church, but to say that the poor had no share in pagan religion is too simplistic. The poor and even slaves were sometimes admitted to the obscene Bacchanalia alongside the wealthy, which were going on in Rome and Greece way prior to Christianity.

Another theory is that Christianity grew because of its acceptance of women. Christianity did much to elevate the role of women in society; but women were always accepted in pagan religions as well; some cults were exclusively made up of women, like the Bacchanalian mysteries, which were led by women and originally reserved exclusively to them. We could also mention the priesthood of Cybele and other cults, which (though they were shameful) cannot be said to have restricted women in any sense. Christianity’s elevation of the status of women was gradual, working through society over many centuries, and was scarcely discernible to the average pagan of the Roman Empire. Christianity’s effect on the status of women was not as radical a break with pagan tradition as some would assert, and certainly a little bit of social advancement was not enough incentive on its own for Perpetua and Felicity to endure their grotesque martyrdoms. These are weak explanations of why Christianity grew.

But first among the insufficient accounts of the conversion of the empire is the assertion that “Roman roads” accounts for Christianity’s explosive growth, an explanation that is repeated as nauseam with little to back it up. It has even become a standard explanation in Christian circles. A quick web search on Roman roads and Christianity brings up a plethora of not only historical sites but Christian sites where the explanation of “Roman roads” is put forward as a prime reason why Christians should believe their faith spread so fast. Here is a standard quote from an evangelical website:

“The Roman Roads also served Christianity. Although the early Christians often suffered tremendous persecution from the Romans, the Roman Roads permitted the apostles and many of God’s people (particularly those who held Roman citizenship) to travel much more easily, while protected by patrolling Roman troops from detachments who were stationed along the way. It’s actually quite ironic that the infrastructure of the empire that attempted to destroy Christianity also made possible its spread to the very farthest frontier regions of the then-known world.” (1)

I don’t debate anything here; the importance of Roman roads in spreading Christianity, or any message within the empire, is indisputable. But this is listed as the first reason why Christianity spread, and furthermore, no other reasons are given.

Roman roads certainly made travel easy, but that’s an obvious redundancy, like saying that my drive to work was made possible by the car I was riding in. The Roman road system was neither the primary reason for Christianity’s spread nor the only one. Take, for example, the rapid spread of the faith through rural Europe in the so-called Dark Ages: Ireland, Scotland, Germany, Scandanavia, etc. None of these places had the benefit of “Roman roads,” yet zealous monk-missionaries spread the faith there just as effectively, proving that Roman roads were not a prerequisite to the quick and effective spread of the faith.

On the other hand if we do a quick Google search on why Islam spread so rapidly, we can find this enlightening answer:

Although there were Arab conquests, the biggest reason Islam spread so rapidly was not because of the sword, but because of conversion. People were accepting Islam because of the message it was sending and because the Islamic world at that time had such a huge impact in world literature, arts, sciences, and philosophy. (2)

And also this:

When Islam appeared it played to the Arabic sensibility that they were the real chosen people … [it] brought a very real improvement to the sense of worth in the Arabic world.

We can see a notable difference here. Christianity spread because of Roman roads, but Islam spread because it enriched the lives of Arabs through art, science, and improving their “sense of worth.”

Now that we’ve looked at some of these over-exaggerated worldly reasons put forward for the growth of Christianity, it’s time to consider supernatural explanations that account for the conversion of the Roman Empire.

Supernatural Reasons for the Growth of the Church

First and foremost, as a kind of overarching supra-reason behind all the other factors accounting for the growth of Christianity, we must place the will of the Holy Spirit: God wanted the Church the spread to the four corners of the earth and actively intervened to accomplish His will. This is a purely theological statement, and as such, would not be mentioned in secular accounts nor verifiable by purely empirical means, but we ought to keep it in mind as we look at the following other factors, all of which can be viewed as the working out of this one principle in the realm of history. As Christians, we must always call to mind the action of providence behind all that occurs in history.

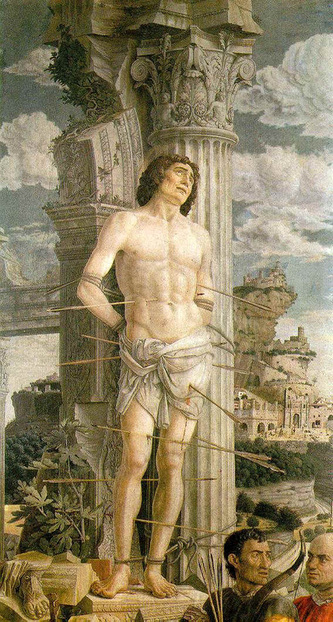

Now, as regards to historical factors, in the first place, we could call to mind the witness of the martyrs. The deaths of the martyrs stood for something substantial and meaningful, as opposed to the frivolous Greco-Roman myths which were amusing and sometimes moving but not ultimately hope-giving or consoling. The fact that the martyrs were willing to be put to death for their faith only made it that much more evident to the pagans that their faith was not worth being put to death over; i.e., that it lacked the intrinsic worth that Christianity seemed to possess. Men and women were put to death for refusing to deny Jesus, because they had a true and proper belief. Certainly pagans believed in their gods, but not in the same way Christians did. G.K. Chesterton pointed this out in The Everlasting Man when he said:

But though [pagan religions] provide a man with a calendar they do not provide him with a creed. A man did not stand up and say ‘I believe in Jupiter and Juno and Neptune,’ etc., as he stands up and says ‘I believe in God the Father Almighty,’ and the rest of the Apostles Creed. Many believed in some and not in others, or more in some and less in others, or only in a very vague poetical sense in any. There was no moment when they were all collected into an orthodox order which men would fight and be tortured to keep intact. Still less did anybody ever say in that fashion: ‘I believe in Odin and Thor and Freya,’ for outside Olympus even the Olympian order grows cloudy and chaotic. (3)

The martyrdoms do not prove the truth of Christianity; they just prove that its adherents found some ultimate value in the religion, something which led others to examine it and to find that “pearl of great price.” Thus, Tertullian is correct when he says “The blood of the martyrs is the seed of the Church.” (4)

In the second place, I am going to quote Dr. Ramsay MacMullen, Professor Emeritus of History at Yale and world renowned scholar on the conversion of Rome who has spent decades studying Rome in the second, third and fourth centuries. In his book Christianizing the Roman Empire he says that the most frequently cited reason (in ancient accounts) of why pagans converted to Christianity was because of belief in miracles; meaning, because one had either seen one, heard about one from somebody trustworthy, or was the object of one themself (5). This factor is certainly neglected in secular accounts of the Christianization of the Empire, but was of pivotal importance in the early Church.

Especially powerful tools of conversion were when miracles accompanied martyrdoms, such as the miracle of the flames at the killing of St. Polycarp and other like incidents. Miracles had an especially potent power in the Roman world due to the natural awe proper to humanity when confronted with a miracle, something which was only magnified by the traditional Roman superstition. These miracles continued confirming the message of the Church well after the Empire’s conversion, and St. Augustine wrote in 419 that “even now miracles are wrought in the name of Christ, whether by his sacraments or by the prayers or relics of his saints” (6). Even today miracles are a powerful yet underrated reason why many people convert.

Third, I would cite the innate superiority of the Christian approach towards life and death over that of the pagans. In the classic work Documents of the Early Christian Church by Henry Bettenson, one can read many of the inscriptions found in the catacombs and the tombs of the martyrs. Here is an example of some of them:

• Here lies Marcia, put to rest in a dream of peace.

• Lawrence to his sweetest son, borne away of angels.

• Victorious in peace and in Christ.

• Being called away, he went in peace

Clearly, when confronted with death—even the agonizing death of a Roman martyr—Christians approached it with a sense of serenity and acceptance. This was unknown to the pagans, among whom death remained a bitter and unfair burden on the human condition, one that was not alleviated by their multitude of gods and goddesses. Let’s look at some pagan tomb inscriptions from the same period:

• Live for the present hour, since we are sure of nothing else.

• I lift my hands against the gods who took me away at the age of twenty though I had done no harm.

• Once I was not. Now I am not. I know nothing about it, and it is no concern of mine.

• Traveler, curse me not as you pass, for I am in darkness and cannot answer.

These inscriptions reveal a pessimism and profound dissatisfaction with the pagan religions’ answers to the most difficult existential problems of life. Regardless of whether a pagan may have derived any happiness from their religion, it is undoubtedly the case that when confronted with issues surrounding death, the destiny of the soul and the meaning of life, the pagans remained dumb. As Christian thinkers became more precise in their language and adept at explaining the mysteries of the faith to the people, the pagans perceived the inherent superiority of the Christian worldview to their own proto-nihilistic pessimism about existence. Furthermore, the fact that all the pagans did end up converting to Christianity is the strongest historical witness to this truth.

The witness of the martyrs, the miracles wrought by the fathers and saints of the early Church, and the philosophical superiority of Christian thought over pagan thought were all part of the Holy Spirit’s grand design for advancing Christianity throughout the world. Is this not a more satisfying account of Christianity’s spread than ‘Roman roads’?

(1) This essay was originally published in an earlier form on the old Unam Sanctam Catholicam blog in 2009. The article in question this quote was taken from has been removed from the Internet and I can no longer find it regrettably.

(2) The same as above for this article.

(3) G.K. Chesterton, The Everlasting Man, Part I, Chap. 5, “Man and Mythologies”

(4) Tertullian, Apologeticus, L:13

(5) Ramsey MacMullen, Christianizing the Roman Empire: AD 100-400 (Yale University Press, 1984), pg. 108-109

(6) St. Augustine, City of God, 22:8

Phillip Campbell, “Why Did Pagans Convert?” Unam Sanctam Catholicam, November 29, 2011. Available online at: http://www.unamsanctamcatholicam.com/why-did-pagan-romans-convert