In the annals of Renaissance Italy we read of a certain brotherhood called the Confraternity of San Giovanni Evangelista della Morte—St. John the Evangelist of Death. (1) The purpose of this association of pious lay brothers was to assist criminals on the brink of execution. No doubt inspired by the example of John the Beloved Disciple at the death of Jesus, the Confraternity of San Giovanni Evangelista della Morte attended to the physical and spiritual needs of the condemned as they prepared to meet their Maker. This particular Confraternity operated in Padua, but similar confraternities existed throughout northern and central Italy.

The job of the brotherhood began on the day before the scheduled execution. The statutes of the Confraternity required two brothers to prepare and feed the condemned their last meal. After having fed the condemned, the brothers were to arrange a final confession and were responsible for contacting and scheduling a priest to administer the sacrament.

The most important task of the brotherhood, however, was to spend time talking with the condemned in order to reconcile them to their punishment. The ideal was to get the condemned man to not only accept his punishment, but to positively welcome it as a manifestation of divine justice. They would encourage the criminal to identify with Jesus Christ and the martyrs, who accepted their deaths willingly. In this way, the brothers attempted to show the condemned that, though they had nothing to offer but their death, the experience could still become meritorious and redound to their eternal salvation.

The examples provided to the condemned differed depending on their mode of execution. If a person was to be hanged, they would be asked to contemplate on their likeness of Christ crucified, who was hung on the cross. Those to be decapitated were reminded of St. Paul, where those who were so unfortunate as to be quartered would be offered St. Hippolytus as their exemplar.

If the victim demonstrated he or she was able to accept their death with genuine contrition and willing to use the occasion to conform themselves to Christ and the martyrs, the brothers would assure him that God would consider his temporal punishment for sin fulfilled and he could expect to go straight to heaven.

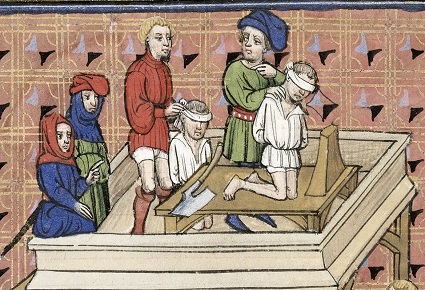

The next day, all the Confraternity brothers would assemble, vested in the habits of the brotherhood; in the case of San Giovanna Evangelista della Morte, this consisted of white capes marked with a black cross. The brothers would flank the condemned and escort him to the execution grounds, in Padua a place called Camposanto, just outside the western gate of the city. Once there, they delivered the condemned to the executioners and stood by, in silent prayer, while the sentence was carried out.

After the victim was dead, it was the duty of the Confraternity to recover the body (if the criminal had been hanged, it was their job to remove it from the gallows; if quartered, to assemble the pieces, etc). Now begun the last act of piety, and one central to the mission of the Brotherhood of St. John the Evangelist of Death: the burial of the corpse as a corporal work of mercy. Sometimes, however, the body would first be delivered to representatives of the local university for dissection. In these cases, the brotherhood would have the added responsibility of gathering up the pieces of the body after the dissection had been performed.

It is probable that the work of burial was why such confraternities were initially formed. The Brotherhood of St. John the Evangelist of Death appears to have emerged around 1300 and was active into the late Renaissance; before this time, the bodies of executed criminals were simply left to rot in the fields outside Padua, which served as the ultimate symbol of their exclusion from the community of the faithful. Confraternities such as San Giovanni Evangelista della Morte were established to fulfill the corporal work of mercy of burying the dead towards for the condemned.

The existence of such confraternities was a beautiful testimony to the way the Catholic Faith sought to turn all of life’s sorrows—even the execution of a criminal—towards Christ. They weren’t concerned with the crimes of the condemned, or whether his sentence was just, or the cruelty or benevolence of his manner of death; their sole aim was to help the condemned get to heaven and honorably bury their corpse after death. It was a tremendously Christian manner of approaching capital punishment.

(1) This confraternity is described in detail in Andreas Vesalius’s On the Fabric of the Human Body, where he discusses them in the context of the dissection of a female criminal executed around 1542 in Padua. See Katharine Park, Secrets of Women (Zone Books: Brooklyn, NY, 2006), pp. 207-215

Phillip Campbell, “The Brotherhood of St. John the Evangelist of Death,” Unam Sanctam Catholicam, June 27, 2022. Available online at: www.unamsanctamcatholicam.com/brotherhood-of-st-john-the-evangelist-of-death