Besides the religious critiques of the Catholic Church offered by Protestants who are offended by her theology, there is also a type of anti-Catholicism that is more sociological in nature. These are the sorts of accusations that Catholicism keeps people poor, that it makes people idle, or that it tends toward political repression. In this article, we will look at the common accusation that Catholicism is fundamentally anti-scientific and answer this objection by appealing to a fascinating study of the empirical data on the subject compiled by British (Protestant) author William Cobbett in his classic work History of the Protestant Reformation in England and Ireland, which Cobbett published in 1826 in favor of Catholic Emancipation.

It had been (and still is) a staple of anti-Catholicism to make the argument that the Catholic religion is bad for the material progress of a country; by its “anti-scientific” bias, Catholicism stifles free scientific and intellectual inquiry and leads to a poverty of brain-power among the people. Advances in medicine, law, science and the arts have typically come from Protestant countries, so the narrative goes. Those countries who embrace Catholicism in its fullness are destined to remain backward and poor.

William Cobbett takes a relentless broadside against this accusation in the opening pages of his book. First, how can one really tell to what degree a whole people or a nation as a whole is “against science” or whether it “stifles intellectual inquiry?” At first glance, such a question seems so broad as to be unanswerable. Cobbett, however, notes that whether or not a country is for or against scientific or intellectual inquiry is something that can be quantified to a certain extent by looking at the number of universally recognized personages exist in a given field from a given country. If Country A has, say, 33 universally acclaimed scientists while Country B has only 12, then it stands to reason that the academic and political climate for science to flourish in Country A is superior to that of country B. We can thus quantify and examine the data in question.

But is there any way to tell when and if a person in a given field is “universally acclaimed”? Cobbett refers to the Universal, Critical and Bibliographical Dictionary, one of the most notable and authoritative reference books of the early 19th century. This work was one of many similar works that were circulating in the early modern period and and consisted mainly of encyclopedia-like entries of famous persons stating their nation of origin and giving a list of any eminent works they were known for, along with tables added as appendices that would compare different nationalities according to in categories. In order for a person to be featured in this or similar works, a person must be “celebrated for their published works…to have a place in these lists a person must have been really distinguished; his or her works must have been considered as worthy of universal notice.” (1) The book is basically a who’s who of early modern Europe, focusing on those whose contributions in science or art are universally recognized and acclaimed, a kind of peer review journal of budding men of science whose work is acknowledged universally.

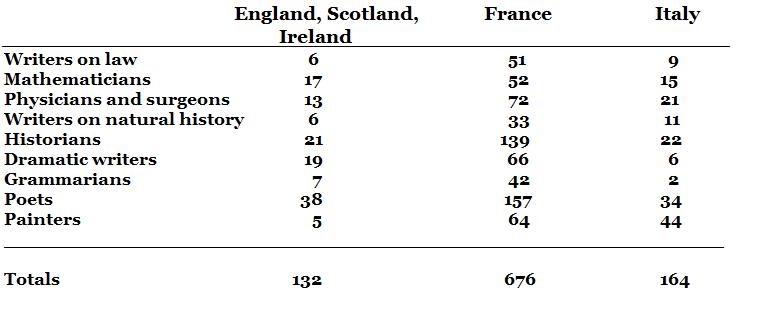

To make his case, Cobbett selects as his samples the three kingdoms of Great Britain, France ,and Italy, the former a solidly Protestant kingdom, the latter two steeped in “monkish ignorance and superstition,” as Cobbett sarcastically puts it. He then adds up all the entries for each kingdom from the year 1600 to the year 1787. One glance at the data immediately disproves the oft-repeated canard that the Catholic religion stifles intellectual activity. Let’s take a look at the data, which I have reproduced on this chart from the one in Cobbett’s book:

Note the tremendous difference between England and France, the latter of which exceeds the former in every category—and recall, this from 1600 to 1787, the period when the Huguenot menace had largely been extinguished and France was entirely under the “monkish ignorance and superstition” of Catholicism. Even Italy, which lagged behind Britain in some categories, comes out on top when all the categories are added together. (2)

There are some objections that could be made. “That’s not fair; England had a civil war.” True, but then again, so did France. Remember the Fronde uprisings that tore that kingdom apart around the same time England was working out its dispute between the Cavaliers and Roundheads? From 1756 to1753 England and France were both equally engaged in the brutal and expensive Seven Years War, which France actually lost; yet France still came out on top. So, war is an weak objection.

A more substantial objection would be that France has thirty percent greater population of England in general, and so it is very obvious that she should have more eminent persons by mere number. That could be a valid objection (though it hardly solves the problem of how Italy, which had a population at the time even smaller than Britain and yet still beat them). Cobbett answers this objection, however, by pointing out that, even if we reduce the number of universally acclaimed Frenchmen by 30% to adjust for the difference in population, we still arrive at 451 for France and 132 for Britain, which is still a disparity of 3.5/1, or as Cobbett puts it, “they had, man for man, three and a half times as much intellect as we, though they were all the while buried in ‘monkish ignorance and superstition’, and though they had no Protestant neighbors to catch the intellect from!” (3)

There really is no excuse. The numbers show that, during the period of the Protestant ascendancy in England, intellectual life suffered tremendously. Certainly there were exceptions; Newton, Swift, Boyle, etc. But perhaps we are only familiar with these names because we ourselves are English speakers and have adopted an Anglo-centric view of our history, elevating the importance of men like Newton while in complete ignorance of men like the famous Jesuit-educated mathematician Claude Gaspard Bachet de Méziriac; extolling the works of Shakespeare but forgetting Moliere, who was more famous in his day than Shakespeare.

The Catholic Church absolutely does not stifle intellectual activity nor scientific discovery. In fact, as the data shows, those countries who adhered to the Faith of their Fathers demonstrated a much greater overall aptitude and intellect than Protestant Britain.

(1) William Cobbett, A History of the Protestant Reformation in England and Ireland (Tan Books: Rockford, Ill., 1988), p 18

(2) I was unable to locate any online or original edition of this book, but the chart appears on page 19 of the 1988 Tan Books edition of Cobbett’s book.

(3) ibid., 19-20

Phillip Campbell, “Eminent Catholics of 1600-1787,” Unam Sanctam Catholicam, February 15, 2013. Available online at: http://www.unamsanctamcatholicam.com/eminent-catholics-of-1600-1787