Much of what we know about the growth of the Church in Palestine in the 5th century comes from the hagiographical works of Cyril of Scythopolis (d. 559), a Palestinian monk of the Great Lavra of St. Sabas in the Kidron Valley. Cyril’s seven hagiographies on the great saints of the Judean desert, called Lives of the Monks of Palestine, provide a wealth of historical information on the state of monasticism and the Christian religion in the Holy Land during the very formative 5th century. (1) His life of St. Euthymius is of particular interest as it chronicles how Christianity came to the pre-Islamic Arabs living on the outskirts of Judea.

The Wanderings of St. Euthymius the Great

Cyril’s vita of St. Euthymius tells us that St. Euthymius (377-473) was an Armenian who made a pilgrimage to Jerusalem when he was 29 years old. After visiting the holy places, Euthymius toured the Judean desert and visited the hermits who were living there. These men made a profound impact on St. Euthymius; Cyril tells us that “He visited the God-fearing fathers who lived in the desert, and as he learned the virtue and way of life of each one, he stamped this on his own soul.” (2) Euthymius decided to take up the life of a monk and settled at one of the small monastic communities (called Lavras or Lauras) then cropping up all over the Judean desert.

Eastern monks of this age did not necessarily commit to spending their entire lives in one Lavra, as did later monks who were bound to specific monasteries. Rather, they tended to abide in a certain place for so long until some spiritual inspiration prompted them to move elsewhere. St. Euthymius thus wandered about the Judean desert, sometimes living in solitude, sometimes living in community and founding monasteries. Eventually he and some companions settled in a cave that is today Mishor Adumim in the West Bank. The cave overlooked a stream called Wadi Dabor, providing Euthymius and his companions with fresh water.

Sheik Aspebet the Saracen

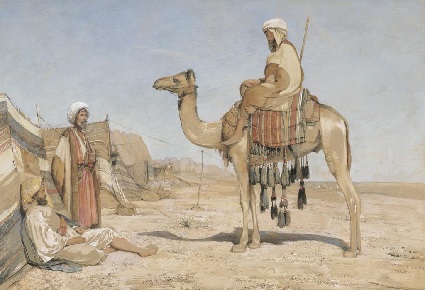

Living on the outskirts of the civilization, St. Euthymius frequently came into contact with Saracen merchants who passed through the desert on their various journeys. These Saracens were Arab speaking Bedouins, no doubt passing between Arabia and Damascus on commercial ventures. The Saracens did not welcome St. Euthymius’s presence near the Wadi Dabor; presumably the resentment had to do with rights to the waters of Wadi Dabor. They harassed the monks, disturbing their solitude and making it difficult to persevere in their vocation.

St. Euthymius was disposed to ignore the ill-treatment of the Arabs and commend the matter to God in prayer, but one of his younger companions, Theoctistus, decided to go visit the leader of the Saracens to see if he could smooth things over. He went out into the desert to seek the Saracens and was given a conference with the Bedouin sheik, Aspebet. This Aspebet was a man of considerable rank among the Bedouin; he was not only a Saracen chieftain, but a Sassanid phylarch—cavalry commander—who, in times of war, transformed his Bedouin caravans into cavalry units that could be incorporated into the Sassanid regular army. He had, however, switched his allegiance to the Byzantines, who were in the ascendancy at that time and was, for this reason, inclined to hear out what this Greek speaking monk had to say.

Theoctistus told Aspebet that he and his companion Euthymius sought only to live in peace and meant no harm to the Saracens or their activities. When Aspebet heard the name of Euthymius, his jaw dropped. He had heard of the holy man Euthymius, but did not realize the ragged monk living in the cave above Wadi Dabor was the same. Aspebet told Theoctistus of his son, Terebon, who was suffering from a terrible malady that left one half of his body withered and paralyzed. He related that Terebon had a vision of Euthymius and was directed to seek him out. Now that Aspebet knew the identity of the holy man, he was eager to bring his son to him. Theoctistus was reluctant, but Aspebet was so excited that he produced his young son and compelled him to show his withered members to the monk. Moved by the son’s plight, Theoctistus consented to arrange a meeting between Aspebet, Terebon, and St. Euthymius.

When St. Euthymius saw the lad, he made the sign of the cross over him and healed him at once. The shocked Bedouins acknowledged the power of the Christian God and professed belief in the name of Jesus. The Bedouins encamped across the Wadi while St. Euthymius spent some time catechizing them before baptizing them in a font in the corner of his cave. A mystagogical period of forty days followed the baptisms, during which Euthymius instructed them in the mysteries of faith. Euthymius told them they were no longer Ishmaelites born of Hagar, but children of faith, descendants of Sarah.

Aspebet was given the Christian name of Peter. In thanksgiving, Peter built a cistern and a bakery for the growing monastery of Euthymius.

Bishop of the Camp of Tents

Aspebet-Peter was a commanding figure among his people, and his baptism was followed by a wave of conversions among the Saracens, not only of Aspebet’s tribe but of neighboring clans as well. The coming years saw the expansion of Christianity among the Arabs until St. Euthymius began to be concerned about the pastoral needs of their community. St. Euthymius went to Juvenal, Bishop of Jerusalem, and asked him to ordain a bishop for the Arabs. Euthymius believed that such a ministry could not be entrusted to any of the clergy from the city; though Christian, the Saracens maintained a nomadic lifestyle that would not be understood by urbanized clergy. Euthymius thus proposed a bishop from among the Saracens themselves, and Aspebet-Peter was put forward as the most suitable candidate. Juvenal agreed, and Aspebet-Peter was ordained to the episcopacy in the year 425. Since every bishop needs a see, Peter was named Bishop of Parembole—which is not a city, but a region of the Judean desert. Parembole was created as a suffragan of Jerusalem, unique because it included not a single city nor village; it was composed entirely of Bedouin encampments. For this reason, Euthymius called Peter “Bishop of the Camp of Tents.”

One unique aspect of Aspebet-Peter’s episcopacy is that he did not resign his temporal office of sheik when he assumed Holy Orders. He was a sheik-bishop who held supreme civil and religious authority amongst the Arabs throughout his tenure. Though this arrangement was unique to Aspebet (after his death the offices of sheik and bishop were divided), one cannot help but notice the portent of the future Arabic mode of religious governance under Islam, when political and religious power were united in the office of the Caliph.

Six years after Aspebet’s ordination, in 431, the Council of Ephesus opened to settle the Nestorian controversy. Aspebet-Peter traveled to Ephesus and represented the Arab Christians as a Council Father. After his return from Ephesus, he returned to the Judean desert and lived in close proximity to his spiritual father Euthymius for the remainder of his days.

The Arabs of the Judean Desert

Here Cyril of Scythopolis ends his tale of Aspebet-Peter; we do not know how he died or when, but Cyril assures us of the truth of his story, saying it was told to him personally by the Christian Sheik Terebon II, the great-grandson of Aspebet-Peter.

The Arabs of Judea shared Aspebet-Peter’s deep reverence for their spiritual father, St. Euthymius. In time many of them would join Euthymius in his monastery; after his death, more would come and settle in other Lavras around the Judean desert. Such was the state of things when Cyril of Scythopolis wrote in the mid-6th century—the Judean desert had become home to a thriving community of Arab Christians numbering in the thousands with entire monasteries occupied by Arab-speaking Christians.

This proliferation of Arab Christianity in the 6th century was a portent of things to come, and a sign of God’s providential care for His Church. In the 7th century the Arab-speaking Muslims under Caliph Umar overran Palestine, seized Jerusalem in 637, and swept away the remnants of Byzantine power. Under the Islamic regime, Arabic became the lingua franca of Palestine, displacing Greek. It was the Arabic monks in the monasteries established by St. Euthymius who would be responsible for the first translations of Christian writings into Arabic and the beginning of Christian Arabic literature. (3) The encounter between Christian monasticism and Arabic literature would have profound effects on the theological thought of the Church, especially once the texts produced by these Christian monks were translated into Latin and made their way west during the Crusades.

This was all set in motion because one holy man sought solitude in cave in the desert.

“Oh, the depth of the riches and wisdom and knowledge of God! How unsearchable are His judgments and decisions and how unfathomable and untraceable are His ways!” (Rom. 11:33)

(1) The seven hagiographies cover the lives of Sabas the Sanctified, Euthymius the Great, John the Silent, Cyriacus the Anchorite, Theodosius the Cenobiarch, Theognius, and Abramius.

(2) Cyril of Scythopolis, Lives of the Monks of Palestine, 14

(3) See Robert L. Wilken, The Land Called Holy (Yale University Press: New Haven, CT., 1992), pp. 154-162

Phillip Campbell, “Aspebet-Peter, Bishop of the Camp of Tents,” Unam Sanctam Catholicam, July 24, 2022. Available online at http://www.unamsanctamcatholicam.com/2022/07/24/aspebet-peter-the-bishop-of-the-camp-of-tents