Mainstream historiography, whether Catholic or secular, has been favorable to Pope John XXIII. Though it has been over half a century since his death, he is still praised as “Good Pope John” and the “Universal Parish Priest.” That he is held in such regard is remarkable for a pope whose pontificate was less than five years. Of course, his historical significance arises primarily from his decision, shortly after his election, to summon the Catholic Church’s twenty-first ecumenical council, Vatican Council II. He is lauded as a visionary thinker whose decision to “open the Church to the modern world” was responsible for ushering in the “riches” of the post-Conciliar era. The name of John XXIII will be forever linked with the Second Vatican Council.

This is ironic, as his role within the council is exaggerated. While he did convene and open the Council’s proceedings in October of 1962, he succumbed to stomach cancer eight months later and died without confirming any of the council’s documents. This task would fall to his successor, Pope Paul VI, who, despite his much longer reign and undeniably greater role in the Council, is much less popular than John XXIII. It is only natural to ask why this is so, and whether the memories of some of his devotees align with the reality of the man himself, especially with regards to his views of the papacy and the Church.

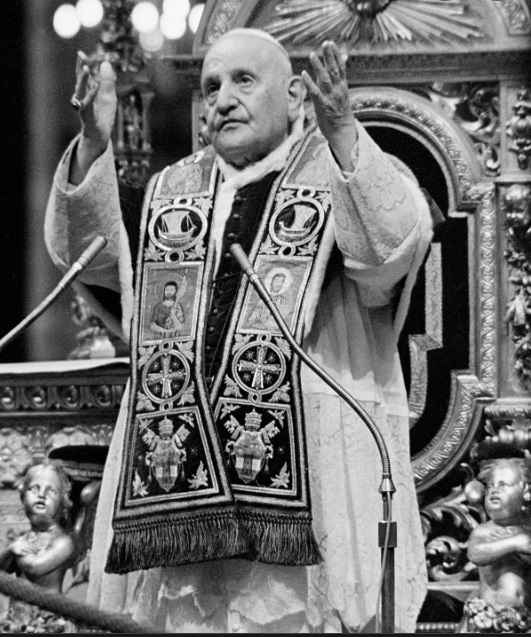

Many would point to Pope John’s personality as the primary reason for his beloved status. This is perfectly understandable. After all, Pope John was the first pope since Blessed Pius IX’s imprisonment in the Vatican to enter the city of Rome proper. Visiting children in the hospital or prisoners behind bars after almost a century without papal contact was certain to leave an impression upon Italians and the world at large. On this note, it is common to see references to Pope John’s warmth, friendliness, and likeability in contrast to the more austere appearance and demeanor of his predecessor, Pius XII. Anecdotes to specific events relating to Good Pope John about, often about a personal encounter that included a witty, friendly, or optimistic statement by the pope—often with no indication of where the story originated.

There’s nothing wrong with this, and I don’t doubt that many, if not all, of these events really did occur. With this being conceded, there is another element in the popular historical reconstructions of “Good Pope John” that transcends his personality and reflects more on his being a champion of what could perhaps be called “liberal” or even “non-dogmatic” Catholicism. This is most commonly seen in paens from certain circles lamenting that what the Church needs is another John XXIII. Such wailing and gnashing is typically a reaction to decisions by popes of the post-Johannine era that the mourners regard as authoritarian, heavy-handed, or otherwise exercising the power of the papacy as it has been viewed by the Catholic Church for millennia, not to mention as dogmatically defined by the prior Vatican Council in 1870.

Historian Garry Wills is probably the best example of this phenomenon. His book Papal Sin has a denunciation of almost every pope of the last century, except for John XXIII, who he refers to as his “hero” and a “truth-teller.” Pope John is the only pontiff who receives such accolades in the course of the whole book. Even the book’s blurb goes out of its way to mark Pope John as an exception among his fellow popes.

Another noteworthy promoter of this view of John XXIII’s legacy is Fr. Richard McBrien, a theologian and professor of theology at the University of Notre Dame. In 1993, he praised John XXIII for introducing “new life” and “passion” to the Church after centuries of “inflexibility and isolation.” His consideration elsewhere of Pope John as “the most beloved, ecumenical, and open-hearted pope in history” (1) demonstrates his great admiration, even as he habitually lamented the “rigid authoritarian” papacy of John Paul II. And who can forget Vice-President Biden’s erudite comments about how he is a “Pope John XXIII guy, not a Pope John Paul guy” (2) and how this distinction made it appropriate for him to support abortion?

These gentlemen are not alone. Theirs is a popular narrative. However, it seems to lean heavily on anecdotes or some sort of psychic extrapolation from Pope John’s admittedly marvelous personality. Whether or not it is accurate is a different matter. Absent from most of these recollections is what the Holy Father actually thought about the Petrine Office and how he conducted himself while occupying it. It may come as a surprise to some, but the nature of the papacy was a frequent topic of John XXIII’s discourse and something that he held in much higher esteem than those who long for another of his character. One cannot, for example, imagine the level of apoplexy that would have exploded if Cardinal Ratzinger, upon his election to the Chair of Peter, been crowned with the triple tiara and pomp that was afforded to Cardinal Roncalli. The response might be equally as violent if these masses were confronted by the Johannine magisterium. Properly paying homage to a man’s memory should mean a truthful evaluation of his principles. Otherwise, we are not honoring the man but rather a figment that we’ve constructed for our own purposes. That being in mind, let us consider the papal legacy of Pope John.

Naturally, the story begins with a conclave. Cardinal Angelo Roncalli, Patriarch of Venice, was elected to the papacy in 1958. Most sources agree that the various Vatican factions considered him a “compromise candidate” and/or transitional pope who wouldn’t upset any applecarts during what would no doubt be a brief pontificate. After all, he was just shy of his 77th birthday. Time was against him. This wouldn’t matter much, as he announced less than three months later his intention to convene the Second Vatican Council. This announcement was significantly referenced in his first encyclical, Ad Petri Cathedram, promulgated on June 29, 1959. Time Magazine reflected upon it with glowing tones: “Kindly, fatherly Pope John XXIII issued his first encyclical last week, and it proved to be a fatherly message of warning, hope and encouragement.” (3) The remainder of the article focused on the Pope’s social justice themes but also spared a mention for the Pope’s hopes that “the forthcoming Ecumenical Council will move non-Catholic Christians to join the Church.” However, a closer examination will show tones that carried a bit more weight than that. Consider first that Pope John spilled a goodly amount of ink condemning the idea of religious indifferentism, the belief that one religion is as good as another:

“Some men, indeed do not attack the truth willfully, but work in heedless disregard of it. They act as though God had given us intellects for some purpose other than the pursuit and attainment of truth. This mistaken sort of action leads directly to that absurd proposition: one religion is just as good as another, for there is no distinction here between truth and falsehood. “This attitude,” to quote Pope Leo [XIII] again, “is directed to the destruction of all religions, but particularly the Catholic faith, which cannot be placed on a level with other religions without serious injustice, since it alone is true.” Moreover, to contend that there is nothing to choose between contradictories and among contraries can lead only to this fatal conclusion: a reluctance to accept any religion either in theory or practice.

How can God, who is truth, approve or tolerate the indifference, neglect, and sloth of those who attach no importance to matters on which our eternal salvation depends; who attach no importance to pursuit and attainment of necessary truths, or to the offering of that proper worship which is owed to God alone?” (5)

The above material is utterly contemptible to so many Catholics and non-Catholics of the modern age. One can envision the sneering accusations of “triumphalism” that would foam up from so many of the masses if Pope Benedict made such comments. Just recalling the firestorm following his publication of Dominus Iesus back in 2000 should suffice for a comparison. Despite using docile language when compared with Pope John’s words, the CDF declaration was roundly criticized by Fr. McBrien who complained, with what must have been unintended irony, that the document lacked “a more positive, less adversarial, tone-something more in line with the historic address of Pope John XXIII at the opening of the Second Vatican Council.” (6)

Worse than claiming that there is one, true religion, Pope John then commits the unpardonable offense of identifying that religion with the Catholic Church, specifically under the rule of Peter as the Vicar of Christ:

Indeed, the Catholic Church is set apart and distinguished by these three characteristics: unity of doctrine, unity of organization, unity of worship. This unity is so conspicuous that by it all men can find and recognize the Catholic Church.

It is the will of God, the Church’s founder, that all the sheep should eventually gather into this one fold, under the guidance of one shepherd. All God’s children are summoned to their father’s only home, and its cornerstone is Peter. All men should work together like brothers to become part of this single kingdom of God; for the citizens of that kingdom are united in peace and harmony on earth that they might enjoy eternal happiness some day in heaven. (7

While this might be shocking to moderns both in and out of the Church, it wouldn’t be the least bit extraordinary to either group a few decades ago. The claims of the papacy were well-known. They hadn’t changed. They were reiterated by Pope John even before this inaugural encyclical, when he expressed them to the bishops assisting at his coronation:

The Saviour Himself is the door of the sheepfold: ‘I am the door of the sheep.’ Into this fold of Jesus Christ, no man may enter unless he be led by the Sovereign Pontiff; and only if they be united to him can men be saved, for the Roman Pontiff is the Vicar of Christ and His personal representative on earth. (8)

Pope John would not ignore these themes during Vatican II’s preparatory period. With less than a year to go before the Council’s opening, the Church had the occasion to celebrate the fifteenth centennial of the death of Pope St. Leo the Great, who is historically known as a master expositor of the doctrines of papal supremacy. Perhaps recalling not only Pope Leo’s own interaction with an ecumenical council, that of Chalcedon, but also his clashes with heretical and schismatic bishops who met in defiance of the Pope and the True Faith in the infamous Robber Synod of Ephesus, Pope John devoted the his sixth encyclical, Aeterna Dei Sapientia, to commemorating his illustrious predecessor. More than just reciting Pope Leo’s outstanding accomplishments or the critical events of his reign, Pope John used the anniversary specifically to concentrate on “The See of Peter as the Center of Christian Unity.” If there was any doubt would have lingered regarding Pope John’s beliefs about the parameters of papal authority following the above-mentioned comments, his encyclical on St. Leo would dispel them all. From Pope John’s perspective, acting as the “center of Christian unity” is not the role of a figure-head or some sort of purely symbolic or ceremonial function. It is the guarantee that what claims to Catholic is actually Catholic:

To preserve this unity of faith, all teachers of divine truths—all bishops, that is—must necessarily speak with one mind and one voice, in communion with the Roman Pontiff. “It is the union of members in the body as a whole which makes all alike healthy, all alike beautiful, and this union of the whole body requires unanimity. It calls especially for harmony among the priests. They have a common dignity, yet they have not uniform rank, for there was a distinction of power even among the blessed apostles, notwithstanding the similarity of their honorable state, and while the election of them all was equal, yet it was given to one to take the lead over the rest. (9)

He does not hesitate to then tie the papacy’s role as the center of unity to the Second Vatican Council’s push for ecumenism. This ecumenism envisioned by Pope John is nothing other than the return of non-Catholic Christians to the Catholic Church:

Unfortunately, however, the sort of unity whereby all believers in Christ profess the same faith, practice the same worship and obey the same supreme authority, is no more evident among the Christians of today than it was in bygone ages. We do, however, see more and more men of good will in various parts of the world earnestly striving to bring about this visible unity among Christians, a unity which truly accords with the Divine Saviour’s intentions, commands and desires; and this to Us is a source of joyous consolation and ineffable hope. This desire for unity, We know, is fostered in them by the Holy Spirit, and it can only be realized in the way in which Jesus Christ has prophesied it: “There will be one fold and one shepherd. (10)

This is a stark contrast to theologians such as Fr. McBrien, who in his book Catholicism, portrays the ecclesiology of Vatican II thusly: “Christian unity is a matter of restoration, not of a return to Rome” and that the view of the Council “differs from the pre-Vatican II understanding of the Catholic Church as ‘the one, true Church of Christ.” (11) While Pope John insists that unity under the rule of the Supreme Pontiff is already present in the Catholic Church as a distinct mark and identifying characteristic, others who claim to be his biggest fans somehow not only fail to mention this, but profess the exact opposite of what the Holy Father actually says. Nor is this mirror vision strictly applicable to John XXIII’s teaching moments. Everyone knows the story of his introducing himself to a Jewish audience as “John, your brother.” Few seem to acknowledge moments of ecclesiastical discipline, like the Roman Synod of 1960. His promotion of Cardinal Bea as the Church’s point man on ecumenism is lauded in most modern circles. That applause turns into complete disavowal when the conversation turns to Cardinal Alfredo Ottaviani, who Pope John chose to head the doctrinal watchdog of the Holy Office.

Perhaps this is an unreasonable analysis. Perhaps I am not being objective, and the popular portrayal of Pope John XXIII as a theological liberal with less regard for Catholic dogma is correct. It’s worthwhile to mention, though, that others have noticed a similar dissonance. Paul Blanshard, (in)famous for his work American Freedom and Catholic Power, was one of the last century’s most vehement critics of the Catholic Church. In his commentary on Vatican II, Mr. Blanshard welcomed what he perceived as items rejecting prior Church doctrine and postures. (12) Curiously, he ascribes none of these positions to Pope John. Blanshard dealt head-on with the Pope’s insistence on his own supremacy and the idea of any Christian unity as being that of the Catholic Church and Hers alone. Calling Cardinal Roncalli both a “Catholic fundamentalist” and a “pioneer of considerable independence and courage,” Blanshard provides a succinct sketch of his early career and papacy. Throughout this historical tour, Blanshard is respectful of the pope as a man, while being simultaneously horrified by his views on religion. Even though he takes time to praise certain elements of Pope John’s most oft-cited (even today) encyclicals, Pacem in Terris and Mater et Magistra, Blanshard reiterates on almost every page that, whatever the pope’s sympathetic personality traits may be, the world is still dealing with a man that is committed to the “ecclesiastically egocentric” Catholic view of his position.

While he engages in inflammatory rhetoric, Blanshard’s point is well-taken. He cannot make Pope John’s words anything other than what they are. His emotional reaction to those words aside, it is difficult to understand how one can use them to construct the Johannine image that is so exalted by some circles today. Blanshard himself was puzzled by this, writing “All this is extremely conventional Catholic doctrine but in light of John’s later reputation as the greatest ecumenist of modern times, the language seems strange.”

Strange indeed that such a significant portion of a renowned pope would be lost. It might be a coincidence or other anomaly that the two encyclicals that are, per John’s own words, most connected with the theme of the ecumenical council he convoked, an event outstanding in history and in his pontificate, are completely ignored. By contrast, the two that do not even mention the Council (Mater et Magistra and Pacem in Terris) are presented as landmarks and most indicative of his thinking. How does this happen? How does an individual such as Paul Blanshard identify these critical components of Pope John’s magisterium, while professed Catholics, theologians even, seem completely ignorant of their existence?

First, let’s not pretend that individuals as intelligent and educated as, say, Mr. Wills and Fr. McBrien, are ignorant of Pope John’s teachings. Second, we must ask ourselves what the possible motivation would be for claiming a certain view of John XXIII as compared to what he actually thought, wrote, and said. The answer is obvious. By insisting upon him as “the greatest ecumenist of modern times” and so forth, the individuals in question are able to promote their own views of ecumenism and the papacy under some sort of mythical imprimatur from a pope who everyone already holds in high regard for his personal warmth and sanctity.

We know these issues are close to the hearts of the individuals involved. Whether it’s Dominus Iesus or the recent CDF proclamations identifying the Church of Christ with the Catholic Church, there always seems to be a firestorm lurking for anyone who would make the same sorts of suggestions that Pope John did, even if in more docile tones. Such parties know that their own views are at odds with Church teaching, so the faux imprimatur is vital if they are to distort or denigrate that teaching. This reaches beyond the individual teachings of Pope John and to the teachings of the Second Vatican Council itself. After all, it’s much easier to paint the Council’s outreach to non-Catholics in a less dogmatic, more ambiguous fashion if we ignore Pope John’s pleas for the separated brethren to return to Rome. Since John XXIII was already known for his personality rather than his teachings, it has been all the easier for dissenters to continue to emphasize the former to the detriment of the latter.

This hagiography of dissent is most amazing since it has happened with impunity. Thanks to the internet, the Pope’s words are available for all to see. There is no reason for Pope John’s profound appreciation for papal authority and the unity of Christ’s Church to be hidden any longer. With so many crises striking at the Church all at once, we need words of encouragement like this from a figure who always engendered the trust and devotion of the masses. More importantly, his passionate appeals to those he referred to as “poor unfortunates outside the Church” (13) should be broadcast to the world at large as a testament of his love for all people. The world needs to hear the Vicar of Christ’s call to “return to the abode of [their] forefathers.” [14] How shameful to have Pope John’s vision of hope targeted for destruction in the name of adoring a false image dedicated to false doctrines.

(1) McBrien, Fr. Richard. Lives of the Popes, (HarperOne, 1997), pg. 432

(2) http://www.delawareonline.com/article/20081019/LIFE/810190304?nclick_check=1

(3) http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,869179,00.html

(4) ibid.

(5) John XXIII, Ad Petri Cathedram, 17-18

(6) McBrien, Lecture: Dominus Iesus, An Ecclesiological Critique. Centro Pro Unione, January 11, 2001.

(7) Ad Petri Cathedram, 67-68

(8) Benedictine Monks of Solesmes, Papal Teachings: The Church. St. Paul Editions, 1962,

(9) John XXIII, Aeterna Dei Sapientia, 41

(10) ibid., 67

(11) McBrien, Catholicism. HarperOne, 1994; pg 687

(12) Blanshard, Paul. Paul Blanshard on Vatican II. Beacon Press, 1966.

(13) Pope John XXIII, Journal of a Soul, Entry of August 10, 1904 (Image Books: 1999).(14) Ad Petri Cathedram, 84.

Lawrence McCready, “The Lost Legacy of John XXIII,” Unam Sanctam Catholicam, March 3, 2013. Available online at: http://www.unamsanctamcatholicam.com/2022/04/the-lost-legacy-of-john-xxiii