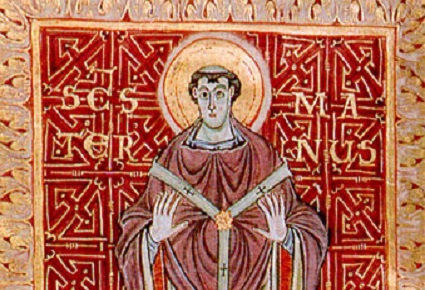

St. Maternus is a semi-legendary figure from the history of the Church of Cologne who was believed to have been that diocese’s first bishop, his episcopacy reputedly lasting from 88-128. The episcopal succession of Cologne prior to the year 285 is uncertain, and many legends surround the character of St. Maternus—for example, that he was the son of the widow of Nain raised from the dead in the Gospel of Luke.

The Legend

The most widely circulated legend regarding Maternus, however, concerned the staff of St. Peter. According to this myth widely circulated in the 9th-13th centuries, Maternus was a subdeacon of the Church of Rome during the pontificate of St. Peter. St. Peter consecrated one Eucharius to found a church in the Roman province of Belgica, assisted by the deacon Valerius and by Maternus the subdeacon.

But en route, Maternus died in Elleum (modern day Ehls) in the region of Alsace. Maternus was considered indispensable to the work of Bishop Eucharius, and so the surviving members of the party returned to Rome and begged St. Peter to come and raise Maternus from the dead. Instead, St. Peter entrusted his episcopal staff to Eucharius and told him to touch it to the dead man. Eucharius returned to Elleum with the staff and touched it to the body of St. Maternus, who immediately returned to life. The miracle resulted in the conversions of large numbers of Germans. Eucharius subsequently established his episcopal see in Augusta Treverorum (Trier), becoming that city’s first bishop. The staff of Peter remained in the keeping of Eucharius, who passed it onto Valerius when he died, and then subsequently to Materus, both of whom became bishops. Thus possession of the staff remained in the hands of the German Church.

Medieval liturgist William Durandus of Metz includes this story in his Rationale Divinorum Officiorum, an exhaustive commentary on church rites, vestments, and architecture dating from the late 13th century. He includes the story in the fifteenth chapter of his section on sacred vestments when considering the bishop’s pastoral staff. The legend of St. Maternus is cited as a historical reason why the Pope does not carry an episcopal crozier. By Durandus’ time there were multiple versions of the story in existence. Let us consider Durandus’ retelling of the tale:

“But the Bishop of Rome useth not the Pastoral Staff, partly for an historical, and in part for a mystical reason. The historical reason is as follows:

The Blessed Apostle Peter sent Martial his disciple (whom the Lord made to be His follower when He said, ‘Except ye become as this little child, ye shall not enter into the kingdom of heaven’) with certain others to preach unto the Germans. When they had gone a twenty-days’ journey, Martial’s colleague, Frontus, died, and Martial returned to tell this to Peter; whereupon Peter said unto him, ‘Take this staff and touch him with it, and say ‘In the name of the Lord, arise and preach.’ This Martial did, touching him on the fortieth day after his death; and he arose, and did preach. And it was thus that St. Peter put away his staff from him and gave it unto his flock, nor did he recover it again.” (1)

While the story is sufficiently similar to recognize it as one with the Maternus legend, some elements have changed: Maternus is now Martial, and it is this Martial who raises a dead man rather than who was raised; Martial is identified with a child from the Gospel, but no longer the son of the widow of Nain, but rather the child who was set upon the lap of Jesus when He delivered His teaching about becoming like little children to inherit the kingdom. Durandus is also aware of other versions of the story as well and includes another, presumably because he was uncertain which was accurate:

“But on the other hand, Innocent the Third, Pope, wrote in the Speculum Ecclesiae that Blessed Peter sent his staff unto Eucherius, first Bishop of Trèves, whom he appointed, together with Valerius and Maternus, to preach the Gospel unto the Teutonic people; and to him Maternus succeeded as Bishop, who had been raised up from the death by St. Peter’s staff. And this staff is preserved in the Church of Trèves with great veneration even unto this day; wherefore the Pope useth the staff in that diocese, and none other.” (2)

This version of the story can also be found in Aquinas’ commentary on Peter Lombard’s Sentences, as well as in the writings of Honorius of Autun, Peter of Clugni and others. It was well known in the medieval world. (3)

The Historicity of the Legend of St. Maternus

This historicity of the legend is dubious. The legend seems to confuse Maternus with a much later historical Bishop of Cologne who reigned from 285-315 and participated in the Synod of Arles in 314 to deal with Donatism in Gaul. Later ecclesiastical writers noticed this aberration and tried to correct it by deeming the latter bishop “Maternus II” to distinguish him from Cologne’s legendary founder. Eucharius, Valerius, and Materus also appear in the episcopal list of the diocese of Trier, although far too late to be associated with St. Peter, reigning between 250 and 300 with Maternus being the fourth bishop. Neither the Maternus who appears in the annals of Cologne nor of Trier lived early enough to possibly have known St. Peter. Furthermore, given the absolute prohibition in the early church of bishops changing dioceses, it is hard to see how Maternus could have been a bishop in both Trier and Cologne.

The Staff of St. Peter is at the heart of the legend of St. Materus. Most historians agree that the legend arose as an effort to explain two questions: (1) why the popes did not carry an episcopal crozier, opting instead for the papal ferula (a staff with a knob surmounted by a cross), and (2) the presence of an ancient episcopal staff in Cologne said to have belonged to St. Peter.

It is almost certain that bishops in the time of St. Peter did not carry a liturgical crozier or staff of any sort; in later centuries, depictions of early bishops holding croziers led to the misconception that these were actually used in the 1st century. Croziers were not universally adopted by bishops until the 4th-5th century; the first unambiguous reference to an episcopal crozier is not until the Fourth Council of Toledo in the year 633. So the likelihood that St. Peter ever had an episcopal crozier or staff of any sort is slim.

In addition to this, it is not true that the Bishops of Rome never used an episcopal crozier. From the time bishops began adopting the crozier (around the 5th century), the bishops of Rome used them as well. It is unknown when they were phased out of Roman use, or why. The change probably occurred in Carolingian times, although some suggest the crozier may have been used as late as the 11th century—the ceremonies from the election of Pope Paschal II (1099) record that “a staff was given into his hand,” which has led some to surmise that this was an episcopal crozier. (4) At any rate, the crozier had definitely been abandoned by the time of Innocent III, who noted in his De Sacro altaris mysterio (Concerning the Sacred Mystery of the Altar,”), “The Roman Pontiff does not use the shepherd’s staff.” (5) While the crozier gradually disappeared from the papal regalia, it is false that it was never part of it to begin with.

Description of the Staff

All this makes the question of the staff of Cologne more mysterious. The relic in question first appears in the historical record in the year 980, when Werinus, Archbishop of Cologne, gave the staff to Egbert, Archbishop of Trier. The staff had not long been in Cologne, only having recently been translated there during the episcopate of Bruno I, “the Great” (953-965) as part of his efforts to make Cologne the religious capital of Germany. The staff was enclosed in lavishly decorated reliquary, which was itself then encased inside a wooden box covered with plates of silver and adorned with jewels and a picture of the Twelve Apostles. The records of its movements are inscribed upon it. The staff was later taken to Prague by Holy Roman Emperor Charles IV (1346-1378); it eventually found its way to Limburg Cathedral where it resides today. Cynthia Hahn, historian of medieval art, describes the reliquary in great detail:

“For the modern viewer, the object allows little or no insight into either its meaning or its controversial and dramatic past. One’s first impression is of an entity, glittering, magnificent, static, and undeniably exotic. Over six feet long and covered with gold foil, what could be described as a floating spear, culminates at its apex in a small orb heavily ornamented with gems, pearls, enamels, filigree, and many, many inscriptions.

The inscriptions—in Latin—introduce a series of demands that the object makes upon the spectator. They call upon viewers capable of reading (and close enough to piece together the long series of letters), to recognize the illustrious origin of the relic inside this reliquary, which itself was made in Trier. The first words, “Baculum beati Petri,” claim that this was the very staff of St. Peter, reputed to have been used by an early Bishop of Trier to resurrect a dead man. As a relic, therefore, it claims to be doubly sacred, invested with the indexical aura of having once touched the hands of St. Peter, founder of the Western church, and proven already to be a conduit of miraculous power.

…The enamels on the upper curve of the spherical knob represent the four evangelical beasts, the lower curve is encircled by a similarly worked series of enamels depicting, in the company of Peter himself, three early Trier bishops, each labeled, including Eucharius who was said to have accomplished the resurrection. A third and fourth row of six enamels represent the Twelve Apostles, again with very legible labels. Down the long sides of the staff, paralleling equally long inscriptions, are the low relief portraits of twelve popes and twelve bishops of Trier, ending with the living archbishop and patron of the magnificent object, Egbert [d. 993].

…Series of gems and pearls in fours, sixes, and twelves are repeated among the network of precious stones that encloses the enamels. At the very top of the staff, a cross shape arrangement of emeralds lifted high on beautifully “architectural” settings suggests the eternal cross ruling over the Heavenly Jerusalem, the holy city that is often symbolized by gems recalling its twelve gates.” (6)

Where, then, did this magnificent object come from if it was not an episcopal crozier of St. Peter? There are various possibilities:

Since the staff does not appear in history before the late 10th century and is first mentioned in connection with Archbishop Bruno of Cologne, who had “translated” the relic to Cologne from elsewhere. It may be possible that the relic was a forgery carried out under Bruno’s auspices. This Bruno was none other than the brother of Holy Roman Emperor Otto the Great. He was Duke of Lotharingia from 954, an office he held simultaneously with the bishopric of Cologne. Bruno was thus the most powerful man in Germany after Emperor Otto. He worked tirelessly to make Cologne the cultural center of Germany, extending its cathedral until it rivaled St. Peter’s, assembling a court of the most eminent scholars of Europe, and accumulating relics from all of Christendom to increase the splendor of his see.

The presence of the staff of St. Peter could have been meant to bolster Cologne’s status as the heart of German Christendom against two rivals: Trier, which was older and the chief metropolitan of Germany, and Rome, which Emperor Otto sought to subjugate. The legend of St. Maternus suitably incorporated the person of St. Peter (Rome) and the Church of Trier (in the person of Eucharius). Bruno could have forged this relic, then claimed to have “found” it elsewhere, for the purpose of elevating Cologne above Trier. The emergence of this relic in the historical record at the very moment Bruno was trying to compete with Trier’s primacy and support his brother’s control over Rome is a bit too coincidental.

But after Bruno’s death in 965, Trier and Cologne brokered a peace that necessitated the transference of the relic to Trier, as befitted the senior church in Germany. This translation is what was recorded in 980.

Buts supposing the staff was not a fabrication, it is possible it was the staff of some other ancient bishop which, through the vagaries of time, was confused with St. Peter. Or it could be even that the staff in question did belong to St. Peter or one of the early bishops of Rome, but was not an episcopal staff, but merely a common staff or walking stick, which subsequently became conflated in legend with an episcopal crozier.

The Legend of Maternus as Propaganda

The legend of St. Maternus gained considerable traction during the 12th-13th centuries and the struggle between the papacy and the Holy Roman Empire under the Hohenstaufens. The legend not only offered a credible explanation as to why the popes did not carry a staff, but the giving of the staff to Germany was given prophetic significance. Consider the commentary of imperial propagandist Alexander von Roes (c. 1281), who said of the legend of Maternus, “And this is the reason why the Bishop of Rome does not have an episcopal staff, for Saint Peter, truly, sent it in the spirit of prophecy to the Germans.” (7) In medieval symbolism a staff was never merely a staff—the transfer of St. Peter’s staff from Rome to Germany signified that the care of the Church was to be entrusted to the Germans until the coming of Christ. Consider the staff as a symbol of the supreme episcopal authority of St. Peter. If this staff had been given away by Peter to a German bishop, then it signified the Holy Roman Empire had a kind of divine trusteeship over the papacy. Thus the legend of St. Maternus became another weapon in the war of propaganda waged between the Holy Roman Empire and the papacy in the Middle Ages.

Conclusion

The legend of St. Maternus is a fascinating tale that is uniquely medieval, a tale that weaves together hagiography, competition between episcopal sees, the struggle between pope and emperor, veneration of relics, and medieval symbolism. Whoever the real St. Maternus was, may he aid us by his prayers. Deo gratias.

(1) William Durandus, Rationale Divinum Officiorum, ed. Neville Blakemore Jr. (Fons Vitae: Louisville, KY., 2007), 200.

(2) Ibid., 200-201.

(3) See Thomas Aquinas, In IV. Sententiarum, Dist. 24, Q. 3

(4) Welby Pugin, Glossary of Ecclesiastical Ornament and Costume, see entry under “Pope.”

(5) Innocent III, De Sacro altaris mysterio, I, 62

(6) Cynthia Hahn, “What Do Reliquaries Do for Relics?” Numen, Vol. 57, No. 3/4, Relics in Comparative Perspective (2010), pp. 284-285

(7) Frank L. Borchardt, German Antiquity in Renaissance Myth (John Hopkins Press: Baltimore: 1971), 260