In commentary after commentary of defenders of the Novus Ordo, from liberals to so-called conservatives, a constant point that is stressed in favor of the liturgical innovations of the post-Conciliar era is the supposed superiority of the lectionary of the Novus Ordo to that of the Traditional Latin Mass. The argument goes “Since the majority of the Bible is read in the course of three years, Catholics are exposed to more scripture now than in the Traditional Liturgy, which had only a narrow selection of readings.”

We need to establish that this is not a dispute about translation. To be fair, I’m not concerned with issues of translation. The best arguments against the Novus Ordo are against the Latin Novus Ordo, not the ICEL translation. Defenders of the new rite can always appeal to a bad translation to explain away the endless problems with the fabricated liturgy of Bugnini’s Concilium. They might also refer to Bishops changing the banal and doctrinally questionable translations in favor of traditional ones, such as we saw instituted in Advent 2011. It is simple enough to go back to the source. Forget the ICEL monster. This I do here, and have consistently done when examining questions pertaining to the new rite.

The argument in favor of the new lectionary is essentially flawed because it relies upon numbers and the mere quantity of something as the sufficiency necessary for correct evaluation. Thus, to put it another way it seeks to implement the liturgical reform the way governments try to reform things, by throwing more of something indiscriminately. In this case it happens to be Scripture. Just as truly as government throws money at education, or defense in the desperate hope that things will get better, so the new lectionary throws as much of the Bible at the layman as possible, indiscriminately, in the hope that he will leave the Church knowing something about the Bible. The Traditional Lectionary’s effect, however, is qualitative, focusing not so much on how much of the Bible the man in the pew hears, but rather what the man in the pew hears.

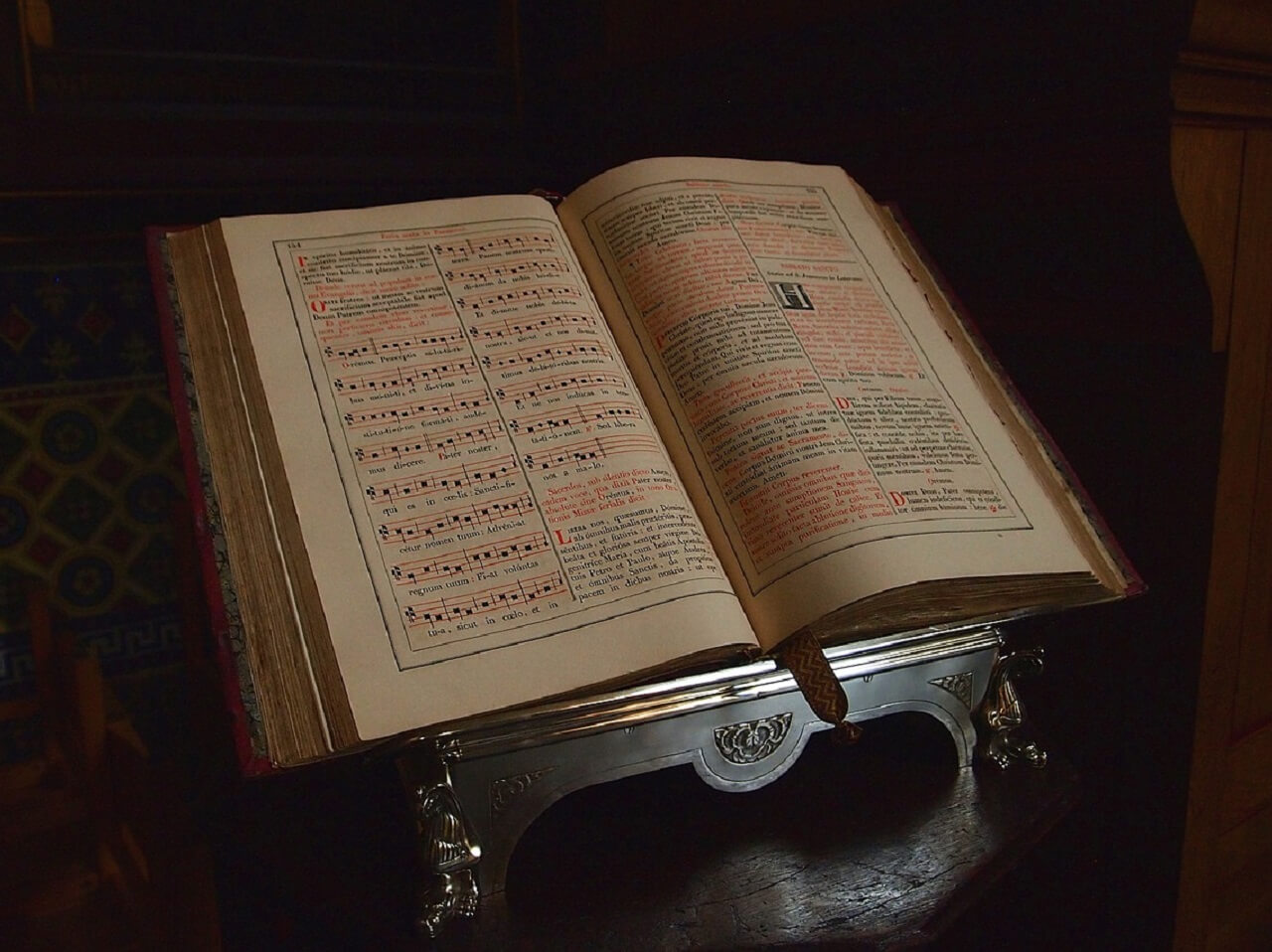

In the Traditional Liturgy, the lectionary was tailored to match the breviary and lead the faithful to a certain idea through its collects, antiphons and other propers; the lectionary of the Novus Ordo often makes use of antiphons and propers that do not match any liturgical objective, prayers that are given just for the sake of it.

The next problem with the argument is that there are many texts of Scripture which are present in the Traditional Rite of Mass but are omitted or made optional in the new lectionary (which, if all the endless options and alternative texts were gathered into one book the thing would plummet to the center of the earth). The text of the great apostasy predicted in 2nd Thessalonians is present on the ember Saturday of Advent in the Traditional Rite, but absent in the new lectionary. Another example was pointed out by Cardinal Stickler speaking on the text of I Corinthians 11:27-29:

“Apart from the pastoral difficulties for parishioners’ understanding of texts demanding special exegesis, it turned out also as an opportunity-which was seized-to manipulate the retained texts in order to introduce new truths in place of the old. Pastorally unpopular passages-often of fundamental theological and moral significance-were simply eliminated. A classic example is the text from 1 Cor. 11:27-29: here, in the narrative of the institution of the Eucharist, the serious concluding exhortation about the grave consequences of unworthy reception has been consistently left out, even on the Feast of Corpus Christi. The pastoral necessity of that text in the face of today’s mass reception without confession and without reverence is obvious.” (1)

Dr. Peter Kwasniewski, a writer for Latin Mass Magazine, had this to say in an October 2007 article on the New Lectionary:

“There is the basic human problem of having more than one year’s worth of readings. A single year is a natural period of time; it is healthy, pedagogically superior, and deeply consoling to come back, year after year, to the same readings for a given Sunday or weekday. This has been my experience. You get to know the Sunday readings especially; they become bone of your bone. You start to think of Sundays in terms of their readings, chants, and prayers, which stick in the mind all the more firmly because they are both spoken or chanted and read in the missal you are holding (more senses engaged). In this way the traditional Western liturgy shows its affinity to the Eastern liturgies, which go so far as to name Sundays after their Gospels or after some particular dogma emphasized. In the old days, the fourteenth Sunday after Pentecost had a distinctive identity: Protector noster was the introit, you knew its melody, and the whole Mass grew to be familiar, like a much-loved garden or a trail through the woods. Nowadays, who knows what the “tenth Sunday of Ordinary Time” is about! It’s anyone’s guess.” (2)

The New Lectionary thus loses some of its meaningfulness and can appear cold. First of all, let us suppose a Latin Novus Ordo where the propers were used, and not replaced by this or that hymn, something which is rubrically incorrect even in the NO. There is no theme, no attempt to unite the psalms sung with the readings. Sometimes they are consistently repeated throughout Sundays of the Year.

Second, while the Sunday readings are on a “3 year cycle”, the weekday readings are on a “2 year cycle”, which is completely nonsensical. If they match up at all to what is read on Sunday it is a pure accident occurring around the time when the planets align. And, who can remember all of these readings? I have known priests who say the Novus Ordo who haven’t a clue of the general order or pace of the readings beyond the Sunday they are in, and one back as well as one forward. It becomes a dead letter and we move onto the next one. And if we consider Lent and Holy Week, in some instances the readings match up and follow a progression, but there is no overall theme matched by the Mass propers or the Divine Office. In Holy week you only hear two passion accounts, on Palm Sunday and Good Friday, where as in the Traditional Liturgy you hear all four, Matthew on Palm Sunday, Mark on Tuesday and Luke’s on Wednesday, while Monday contains a prophecy of our Lord’s death and resurrection.

The whole of the lectionary for the Traditional Mass is contained in the same book as the Missal, and it comprises a modest size book. As I said above, if one was to take the entire Novus Ordo with all of its options, extra prayers, and the lectionary with its endless options and substitutions, it would fall through the altar and wind up in the center of the earth.

Another problem is the fact that the lectionary was arranged by exegetes with “sociological leanings”, while the ancient Roman lectionary was arranged by St. Jerome one of the greatest of ancient doctors apart from Chrysostom and Augustine, and apart from changes and modifications for the saints or new feasts, the propers for the year are unchanged. If we lined up the Traditional Lectionary with the calendar of the Eastern Church (or even that of the Orthodox), one will find striking similarities. Only one epistle reading, not two as in the Novus Ordo. A one year cycle, is unique to both calendars, and to liturgical tradition. The concept of a three, or two year lectionary is a novelty east and west and not even suggested by Vatican II. Sundays after Easter are called “Sundays after Pentecost” by both traditional calendars, and the propers which must always be sung in a Divine Liturgy match up to the epistle and Gospel reading. Lastly, the readings must be sung in the Divine Liturgy, just as they must at a Tridentine High Mass. The Traditional lectionary is linked with and grew out of the common heritage of liturgical development which in spite of different cultures, locations and circumstances, share characteristics coming form ancient practice.

Therefore, for both practical and liturgical reasons, the New Lectionary is a complete novelty, inferior to Catholic tradition. Yet one may ask, how could one reform the Traditional lectionary? There are several Masses for different types of saints, and when there is no regular reading for the saints, the regular readings from the Mass Os Iusti, or some such Mass will be used over and over again, sometimes within the same week. So texts could be found which would match the life of the saint, while this is often not done in the Novus Ordo, and as Dr. Kwasniewski notes in the article I linked, the readings for St. Therese in the Traditional Mass make sense, whereas the ones in the new rite follow the baneful 2 year cycle and have nothing to do with her.

There is but one more consideration. At the average Traditional Mass, one will hear more Scripture than at the Novus Ordo if one is to take the whole of the liturgy into account. The Mass begins with Psalm 42, many of the responses are actually quotes from the Psalms (Adiutorium nostrum…Psalm 69, etc.), a good portion of the offertory prayers are from scripture directly, including all of Psalm 25, many parts of the canon and the priests communion come directly from scripture, not to mention the Last Gospel (John 1:1-18) and the fact that the propers are never skipped, while in the Novus Ordo encountered by 99% of Catholics in the world they are generally skipped, or are repeats from a series of options while in the Traditional Liturgy they are different every Sunday and saints day.

Like all things, the simple fruits of tradition are better than the artificial creations of modernity.

(1) Alfons Cardinal Stickler, “Recollections of a Vatican II Peritus,” Latin Mass Magazine, Witner, 1999. Available online at: http://www.latinmassmagazine.com/articles/articles_1999_WI_Stickler.html

(2) Peter Kwasniewski, “Loss of Liturgical Riches in the Sanctoral Cycle,” Scripture and Catholic Tradition, Oct. 25. 2007. Available online at: http://catholictradition.blogspot.com/2007_10_01_archive.html#7694477137172623016

Ryan Grant, “Comparing the New and Traditional Lectionaries,” Unam Sanctam Catholicam, October 5, 2013. Available online at www.unamsanctamcatholicam.com/2022/06/comparing-the-new-and-traditional-lectionaries